Policy Research for Front of Package Nutrition Labeling: Environmental Scan and Literature Review

Final Report

February 2011

Contract No. HHSP23320095651WC

Prepared for: Kathleen Koehler Department of Health and Human Services Office of Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Office of Science and Data Policy 200 Independence Avenue SW Washington, DC 20201

Prepared by: James E. Hersey, Kelly C. Wohlgenant, Katherine M. Kosa, Joanne E. Arsenault, and Mary K. Muth RTI International 3040 Cornwallis Road Research Triangle Park, NC 27709

This report is available on the Internet at:http://aspe.hhs.gov/sp/reports/2011/FOPNutritionLabelingLitRev/

Contents

1. Background and Purpose1.1 Introduction1.2 Study Objective1.3 Conceptual Framework1.4 Report Organization

2. Methods2.1 Literature Review2.2 Interviews with Experts

3. Identification of Issues3.1 The Public Health Perspective3.2 The Consumer Perspective3.3 The Producer and Retailer Perspective3.4 The International Experience3.4.1 Sweden3.4.2 United Kingdom3.4.3 The Netherlands3.4.4 Australia and New Zealand

4. Summary of Discussions with Experts4.1 Consumer Response to FOP Labeling4.2 Producer Response to FOP Labeling4.3 Retailer Response to FOP Labeling4.4 Public Health Issues Regarding FOP Labeling4.5 Criteria for Developing and Assessing FOP Systems

5. Literature Review Findings5.1 Studies of Consumer Response5.1.1 Attention and Processing5.1.2 Liking, Satisfaction, and Preferences5.1.3 Understanding5.1.4 Effects of Nutrition Labels on Likely Purchase Behavior5.1.5 Effects on Purchases and Consumption5.1.6 Effects of FOP Labels on Diverse Subpopulations5.2 Studies of Producer and Retailer Response5.2.1 Producer and Retailer Implementation Experience and Marketing5.2.2 Effects on Product Introduction and Reformulation5.2.3 Studies of Combined Consumer and Producer/Retailer Response

6. Discussion and Synthesis6.1 Description of Study and General Findings6.2 Data Limitations6.3 Primary Findings6.3.1 Effects on Attention and Processing6.3.2 Effects on Preference and Liking6.3.3 Effects on Understanding6.3.4 Effects on Diverse Consumer Populations6.3.5 Effects on Use, Purchase, and Consumption6.3.6 Effects on Producers and Retailers6.3.7 Combined Effects on Consumers, Producers, and Retailers6.4 Identification of Knowledge Gaps

Appendices

A: FOP Labels Search StrategyB: Discussion Guide for Expert InterviewsC: Summary of Evidence to Address Front-of-Pack Research Questions

Figures

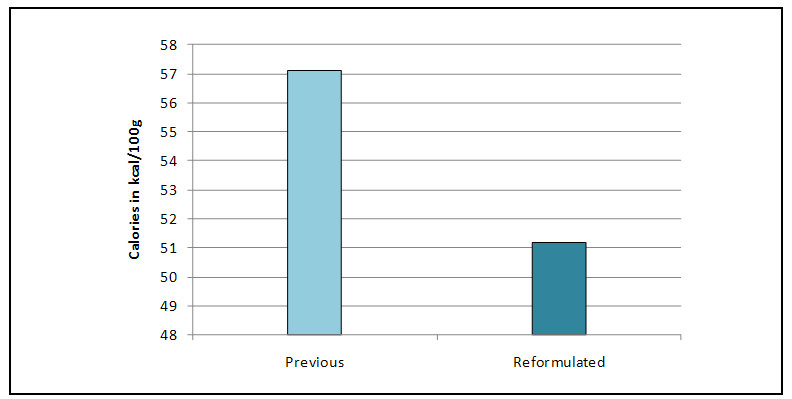

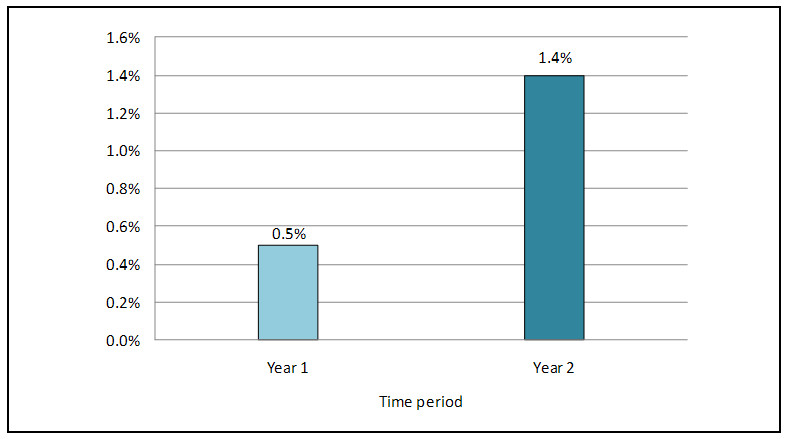

1-1. Conceptual Framework for Producer, Retailer, and Consumer Response to FOP Nutrition Labels3-1. FOP Symbols Used Internationally5-1. Percentage of German Customers Selecting the Healthier Product5-2. Percentage of UK Consumers Selecting the Healthier Product5-3. Percentage of U.S. Consumers Choosing the Healthier Product5-4. Mean Sodium Content for Processed Meats Before and After Implementing the Choices Logo (mg/100 g)5-5. Mean Saturated Fatty Acid Content for Processed Meats Before and After Implementing the Choices Logo (g/100 g)5-6. Mean Caloric Content for Dairy Products Before and After Implementing Choices Logo (kcal/100 g)5-7. Percentage Change in Sales of Starred Foods After the Introduction of Guiding Stars in Hannaford's Supermarkets

Tables

2-1. Search Terms and Databases2-2. Summary of Identified Articles by Category2-3. Quality Criteria Used to Score Identified Articles2-4. Experts Interviewed5-1. FOP Symbols and Shelf-Tag Systems Discussed in This Report5-2. Effects of Consumer Response to FOP on Attention and Processing5-3. FOP Effects on Liking, Satisfaction, and Preferences5-4. Shelf-Labeling Effects on Consumer Response to Liking/Preferences5-5. FOP Effects on Identification of Healthier Foods5-6. FOP Effects on Use of Labels and Likely Food Purchase Behavior5-7. Shelf-Labeling Effects on Use of Labels and Likely Food Purchase Behavior5-8. FOP Effects on Purchases and Consumption5-9. Shelf Labeling Effects on Purchases and Consumption5-10. FOP Effects on Producers and Retailers: Implementation, Reformulation, and Sales5-11. Shelf-Labeling Effects on Producers and Retailers: Sales and Other Benefits6-1. Summary of Findings of Experimental Studies of Effects of Labels on Identifying Healthier Food Choices

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

ES.1 Background and Purpose

Food manufacturers have recently been adding summary nutrition information on the front of packages in addition to the currently mandated back or side Nutrition Facts Panel (NFP). In addition, some supermarkets have added summary information or symbols on shelf labels where the information is more visible to consumers in the shopping aisle. The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Office of Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) want to ensure that front-of-package (FOP) and shelf-label nutrition systems that provide nutrition information or summarize the overall nutritional quality of a food are useful for the consumer and that the nutrition criteria are based on science.

RTI International conducted an environmental scan and literature review on consumer, producer, and retailer response to FOP nutrition labeling and shelf labeling and interviews with key experts on these issues. FOP nutrition labels and shelf tags have effects on consumer attention and processing, liking, understanding, use, and purchases. FOP nutrition labels and shelf tags also might influence sales of food products and stimulate producers and retailers to develop new products or reformulate existing products to improve their nutritional content.

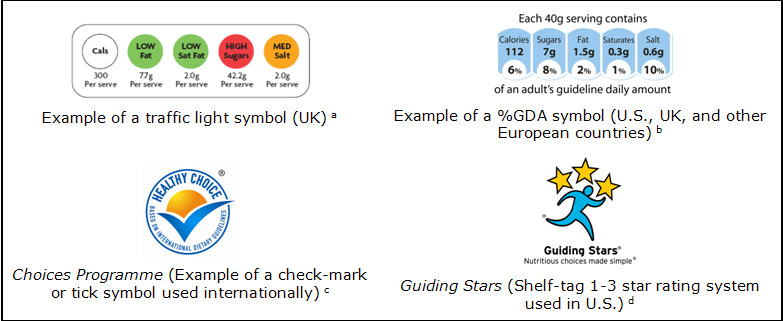

Examples of FOP nutrition labels and shelf tags are shown in Figure ES-1. These symbols are classified into two main categories: nutrient-specific and summary systems. Nutrient-specific FOP symbols display a few key nutrients; examples of these symbols include the percentage guideline daily amounts (%GDA) and traffic light (TL). Summary systems use an algorithm to provide an overall nutritional score. Summary systems can be binary such as the Choices Programme logo, which is a single check mark that is present or absent on foods depending on whether the foods meet specified nutrient criteria, or graded such as the Guiding Stars system, which displays a ranking of one to three stars.

Figure ES-1. Examples of FOP Nutrition Labels and Shelf Tags

a Traffic light symbol reprinted with permission from the Food Standards Agency, UK.b %GDA symbol reprinted with permission from the Food and Drink Federation, UK.cChoices logo reprinted with permission from the Choices International Foundation, Belgium.dGuiding Stars shelf-tag symbol reprinted with permission from the Guiding Stars Licensing Company, U.S.

ES.2 Key Findings

Key findings based on the literature synthesis and as confirmed by the experts interviewed for the study are as follows:

- Consumers can more quickly process simple graphic FOP labels (e.g., labels displaying TL colors or graphic elements) than labels primarily displaying detailed numeric information (e.g., a monochrome %GDA).

- Consumers like and understand nutrient-specific FOP nutrition labels that incorporate TL color-coding more than nutrient-specific FOP labels that emphasize numeric information such as %GDAs or binary summary check-mark symbols. This is especially true for diverse subpopulations, including older adults, individuals with low socioeconomic status, or high body mass index (BMI).

- Text corresponding to TL color-coding that indicates "high," "medium," or "low" levels of negative nutrients appears to enhance consumer understanding of nutrition information.

- Nutrition-conscious consumers are more likely than less nutrition-conscious consumers, or consumers with low socioeconomic status or with high BMI to purchase healthier products as indicated by FOP nutrition labels or shelf tags.

- Effects of FOP labeling on consumers' purchase and consumption habits are unclear because of insufficient research and mixed results of existing research.

- Although less literature was available on producer and retailer response than consumer response, FOP nutrition labels and shelf tags appear to benefit food producers and retailers who implement these systems, because studies suggest that sales of products that are indicated as a "healthier choice" by FOP nutrition labels or shelf labels increase over time.

- FOP nutrition labels appear to stimulate food producers to develop healthier products.

Additional detail on consumer response to FOP nutrition and shelf labeling, FOP and shelf-labeling effects on producers and retailers, combined findings, and knowledge gaps on these topics are provided below. However, several knowledge gaps exist in the literature including limited studies conducted in the United States or lack of studies that compare a TL system against a more graded summary system, such as Guiding Stars.

ES.3 Consumer Response to FOP Nutrition Labels and Shelf Tags

This section reviews findings on consumer response to FOP nutrition labels and/or shelf labels in terms of attention and processing, liking, understanding and identification of healthier food choices, use and purchase or consumption, and effects on diverse subpopulations.

Attention and Processing

- To gain consumers' attention in the supermarket FOP labels should be positioned to stand out against potential "competing" elements on the food package that could distract consumers' attention. "Competing" elements can include any text, graphics, and/or color displayed on food packages by the producer for marketing purposes. One study found that FOP labels more quickly gained consumers' attention if they were large and consistently placed on the top right of food packages.

- Overall, consumers' processing time (e.g., time needed to understand nutrition information) was about 5.8% faster for products with FOP labels than for products without them.

- Simple FOP symbols that emphasize color-coding and graphic elements such as a TL symbol, a single check mark (e.g., Choices Programme logo), or a series of stars (e.g., the Guiding Stars system) more quickly capture consumers' attention than a monochrome symbol displaying the percentage of daily reference intake amounts for specific nutrients (e.g., %GDA). There were limited studies that compared consumers' processing time using different types of "simple" FOP symbols, so it is unknown whether some of these symbols may be easier to process than others.

- Results from one eye-tracking study suggested that an FOP label can perhaps direct consumers' attention to a more detailed nutrition label such as the Nutrition Facts Panel (NFP).

Liking and Satisfaction

- In general, based on studies conducted in the UK and Korea, consumers have favorable opinions regarding FOP nutrition labels, believing that they are helpful in making healthy food selections at the supermarket. However, participants in a focus group study admitted that they may not use FOP symbols in all situations because other factors such as price may sometimes take precedence over nutrition.

- Consumers like simplified nutrition labels they perceive are visually appealing, credible, trustworthy and/or easy to understand quickly.

- Regarding specific labeling schemes liked by consumers, consumers say they prefer nutrient-specific labels that indicate levels of nutrients using TL color-coding such as TL symbols or colored GDAs (e.g., %GDA label with TL colors) as opposed to monochrome GDA schemes or check-mark symbols. It should be noted that only one study compared consumers' preferences for a TL scheme to a continuous or graded summary concept such as stars (e.g., the Guiding Stars system) to find that consumers preferred the TL symbol.

- Based on the results of one study, consumer preferences for specific FOP labeling schemes may be influenced by the complexity of the task: the more complex the task (e.g., the more products' nutrition information being compared) the more likely consumers preferred simple labels, meaning labels incorporating simple graphic elements (e.g., stars) as opposed to %GDA information.

- Consumers with lower income, education or who are less health-conscious tended to have a stronger preference for FOP labels with TL color-coding or graphics compared with other groups.

- A study of shelf labels found that many consumers prefer a labeling system to be displayed on both a shelf label and the food package.

Understanding

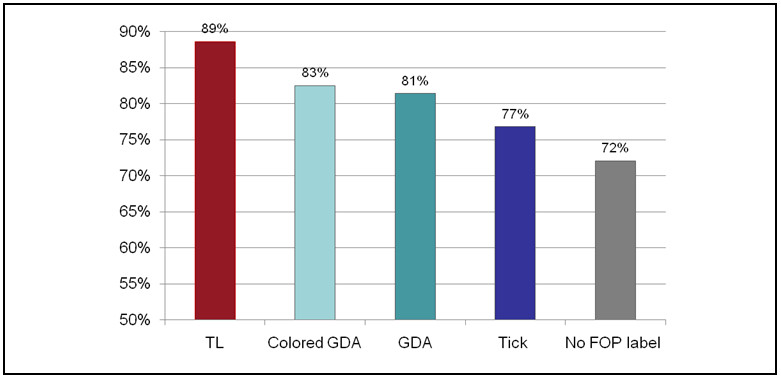

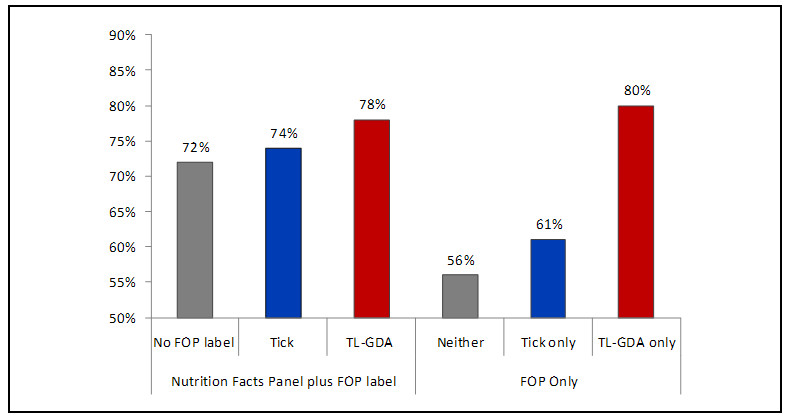

- In most studies that included a no-label condition, consumers were more likely to identify healthier foods in response to a product package with an FOP nutrition label system than to a product package without an FOP nutrition label.

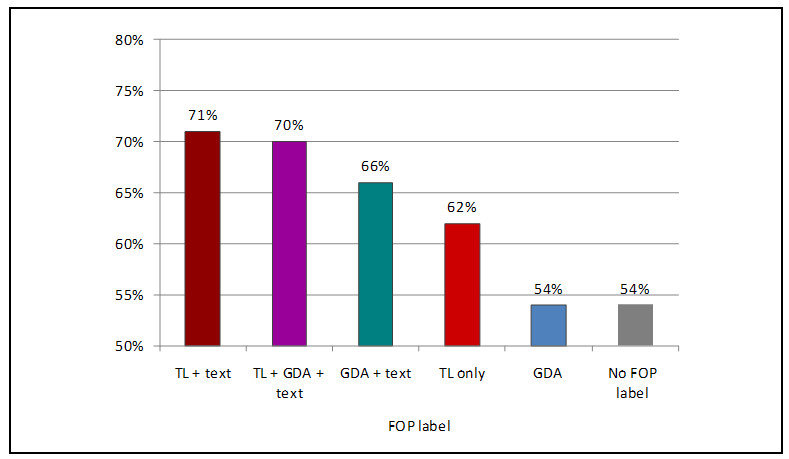

- Most experimental studies that compared FOP labels incorporating TL color-coding, such as TLs or colored %GDAs, to less interpretive nutrient-specific systems, such as the GDA or Percent Daily Intake (%DI), found that consumers could more easily identify healthier foods using an FOP label incorporating TL color-coding. The magnitude of differences in consumer understanding between labels with TL colors and less interpretive nutrient-specific FOP labels were in the range of 10 to 20%.

- Most experimental studies comparing nutrient-specific TL schemes to binary summary FOP schemes found that consumers were better able to identify a healthier food choice in response to a TL nutrition label compared with check-mark or tick symbols. However, it should be noted that few studies compared a TL label system with a more continuous or graded summary rating system such as multiple stars.

- Studies also suggested that schemes incorporating TL colors are easier to understand among consumers who were older or of lower socioeconomic status.

- When considering individual design components of FOP nutrition labels, consumers were most frequently able to identify a healthier food choice when exposed to FOP labels that included TL color-coding and corresponding text indicating "high," "medium," and "low" levels of nutrients. For example, one study investigated exposing study participants to numerous schemes with different combinations TLs, GDA, and text to find that labels incorporating text were the easiest to interpret by study participants. However, TL colors in addition to text further increased performance by about 15%.

Effects on Use, Purchase, and Consumption

- Use of FOP nutrition labels is most common among consumers who are health conscious, of normal weight, and higher in socioeconomic status.

- Some evidence suggests that consumers have a greater preference for foods displaying FOP nutrition labels or shelf-labeling systems and are willing to pay more for these foods. However, studies of effects of FOP nutrition labels on consumers' actual purchase behavior and consumption habits were limited and show mixed results.

- One UK study found that consumers' reported use of FOP nutrition labels was higher than their observed use of FOP labels.

Effects on Diverse Subpopulations

- Older adults, less-educated consumers, and consumers with higher BMI liked FOP nutrition labels that contained simple graphic elements or color-coding, such as a check-mark logo and the TL label.

- Older adults, consumers with low socioeconomic status, and nonwhite consumers generally had more difficulty understanding FOP labels than other groups.

- For consumers of low socioeconomic status and high BMI, TL nutrition labels proved to be the easiest FOP nutrition label to understand compared with %GDA labels. Text indicating "high," "medium," or "low" levels of nutrients is also an important FOP label feature, in particular, for color-blind consumers.

ES.4 Effects on Producers and Retailers

Producer and retailer response to FOP nutrition and shelf-labels can be assessed based on their implementation and marketing experiences and the effects of FOP and shelf labeling systems on product reformulation or new product development.

Implementation and Marketing

- Although limited studies are available on producer and retailer implementation and marketing of FOP nutrition and shelf tags, results suggest that summary FOP systems are beneficial to producers and retailers. Two marketing studies found that consumers, particularly those who are health conscious, reported preferring to shop at stores with summary FOP systems. Another study found that summary systems can provide private label products with increased brand equity (e.g., increased value).

- A UK study conducted after a voluntary call for FOP labeling found that producers are implementing FOP labeling schemes that they believe are less expensive to implement or confusing to consumers.

Reformulation and Development of Healthier Food Products

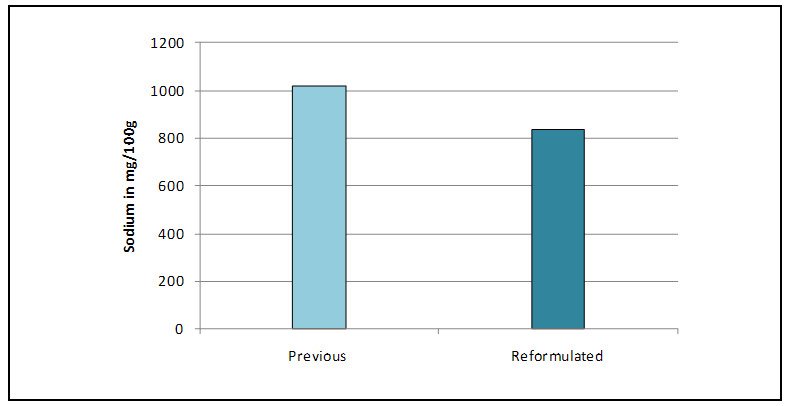

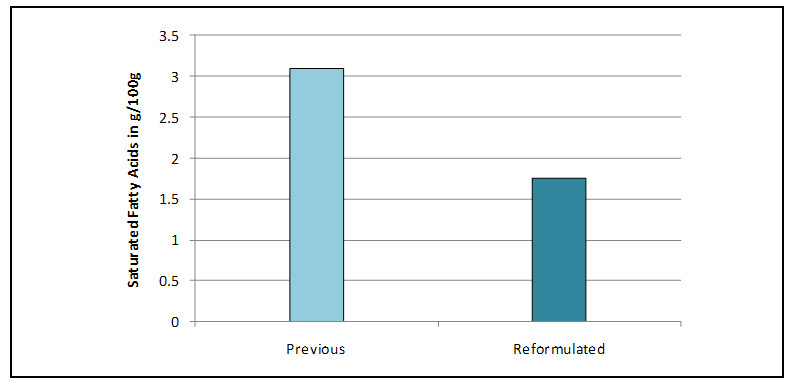

- Although the number of studies is limited, analysis of products before and after implementing FOP labeling suggests that the introduction of FOP labeling has led producers to reformulate products and formulate new food products that have healthier nutrient content. For instance, in the Netherlands, these changes have had considerable effects in prompting the introduction of products that are lower in sodium and saturated fats. In Australia and New Zealand, new or reformulated products have been introduced that are substantially lower in sodium.

ES.5 Combined Effects on Consumers, Producers, and Retailers

Combined effects of consumer, producer, and retailer response to FOP nutrition labels and shelf-labels are as follows:

- Most empirical studies suggest that food products indicated as "healthy" by FOP nutrition schemes or shelf labels will likely increase product sales, implying that producers implementing these systems will likely profit. While a modest increase of 1 to 2% was found for the Guiding Stars program, this program also found that the effects were greater after 2 years than after one, suggesting that effects on sales could increase over time.

ES.6 Knowledge Gaps

A number of research questions need to be investigated to help address important knowledge gaps. These questions include the following:

- What type of FOP labeling would work best in the United States? Most of the studies on FOP labeling have been conducted in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Moreover, the United States has a more diverse population and less vertical integration of producers and retailers than many of those countries.

Also, although a number of studies have compared TL systems with %GDA systems or against a single summary check or tick, relatively little has been done to compare a TL system against a more graded summary system, such as a set of stars.

- What type of FOP nutrition labeling best serves the needs of diverse consumer populations? Studies in Europe and Australia suggest that less-educated consumers and older consumers do a better job of identifying healthy food choices when presented with simpler labels (e.g., TL) rather than more complex formats (such as %GDA). It will be important to assess the effects of alternative FOP labeling systems on the range of consumer populations in this country, including those who are lower in health literacy, those who have children at home, older audiences, consumers of different racial/ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and individuals with disease risks such as obesity or chronic conditions such as hypertension or diabetes.

- What are the interrelationships between the Nutrition Facts Panel and FOP labels in the U.S. market? Little information about the interrelationship between the mandatory Nutrition Facts Panel and FOP symbols is another limitation, especially for understanding the efficacy of FOP labels in the U.S. market.

- What is the influence of competing nutrition claims on the effects of FOP nutrition labeling? An important gap in the research is limited information about the effects of other contextual information, such as nutritional claims provided by food manufacturers on the fronts of packages.

- What is the effect of FOP nutrition labels on influencing consumers to purchase or consume products? There is little evidence on the likelihood or existence of substitution effects, that is, whether and how much consumers consume/purchase products displaying an FOP symbol, particularly a summary type of symbol or a multiple TL symbol with a lot of green lights and whether this might lead to over-consumption of products perceived as healthy.

- What would minimize possible consumer confusion with multiple FOP label systems? One study found that 73% of UK consumers thought it would be confusing if producers used different types of FOP nutrition labels. It will be important to understand what requirements or guidelines could reduce possible confusion of multiple FOP labeling systems and nutrition claims in the United States.

- What are the effects of FOP nutrition labeling on use and purchase? Most research studies we identified were laboratory or Web-based experimental studies; we found limited studies on the effects of FOP labels in actual shopping situations.

- What consumer education best supports appropriate use of FOP labels? It will be important to better understand the effects of broader social marketing, in-store promotions, and consumer education to encourage the understanding and use of FOP labels.

- What are the effects of FOP labels on new product development and reformulation? From a public health perspective, one of the greatest benefits of FOP labels is that they will likely motivate the development and reformulation of products to better satisfy nutritional criteria. It would be useful to develop a monitoring system that would enable the assessment of possible changes in the nutritional content of foods that are sold in response to implementing FOP nutrition labels.

1. BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

1.1 Introduction

Food manufacturers have recently been adding summary nutrition information on the front of packages in addition to the currently mandated back or side Nutrition Facts Panel (NFP). In addition, some supermarkets have added summary information or symbols on shelf labels where the information is more visible to consumers in the shopping aisle. There is interest in ensuring that multiple front of package (FOP) labeling schemes do not cause confusion among consumers; a uniform system based on current science may be optimal.

The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Office of Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) want to ensure that FOP and shelf-label nutrition systems that provide nutrition information or summarize the overall nutritional quality of a food are useful for the consumer and that the nutrition criteria are based on science.

In August 2010, ASPE contracted with RTI International to conduct a two-part project on FOP nutrition labeling. The first part is an environmental scan that includes a literature search of published and unpublished literature relating to the responses of consumers, producers, and retailers on FOP nutrition labeling and shelf labeling and interviews with key experts on these issues. The second part is an evaluation of nutrient criteria underlying summary FOP systems and the development of a summary system. This report describes the results of Part 1 of the project.

For the literature review, RTI reviewed articles published from 1990 to the present in the United States and other countries, while considering differences in labeling regulations in other countries for the interpretation and applicability of these studies. The time period of the search was publications dated 1990 to the present. Our search uncovered a number of review articles and editorials that describe "issues" to be considered regarding nutrition FOP and shelf labeling as well as academic journal articles reporting empirical consumer and producer response studies. For the discussions with experts, RTI conducted interviews with seven experts in nutrition, consumer behavior, and marketing to obtain their views on key issues related to consumer, producer, and retailer response to FOP.

1.2 Study Objective

The objective of this task was to conduct an environmental scan, including a systematic literature review on consumer, producer, and retailer response to FOP nutrition labeling, and interviews with key experts on these issues.

1.3 Conceptual Framework

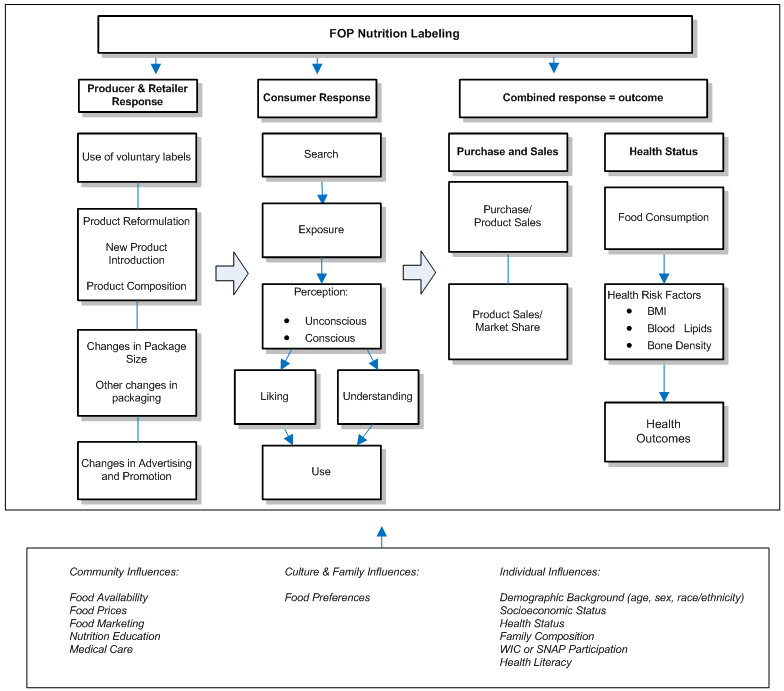

The synthesis of our literature review was organized based on the conceptual framework in Figure 1-1, adopted from a framework presented by Grunert and Wills (2007). Results of the studies are organized by concept, including consumer response, ranging from search and perception to comprehension and use, and retailer/producer response, ranging from effects on product introduction to reformulation. The interview guide was also influenced by this conceptual framework.

Figure 1-1. Conceptual Framework for Producer, Retailer, and Consumer Response to FOP Nutrition Labels

This report explains our methods in conducting a systematic literature review and expert interviews and presents our findings. The literature review uncovered many articles discussing issues related to FOP labeling, which are discussed in Section 3 followed by the results of the expert interviews in Section 4. Findings from the articles reviewed that reflect the Grunert and Wills (2007) conceptual framework are presented and discussed in Section 5, Literature Review Findings. The information learned from the review is synthesized in Section 6.

2. METHODS

This section describes the methods employed in conducting a systematic literature review and in conducting interviews with experts on FOP nutrition labeling.

2.1 Literature Review

We conducted a systematic search to obtain empirical studies and grey literature regarding the topics of FOP nutrition and shelf labeling. The search was conducted from August 31 to September 10, 2010, and the time period specified in searches was for publications dated 1990 to the present. The following databases were searched twice using different sets of key words: PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, CHINAHL, Business Source Corporate, PsycINFO, AGRICOLA, and Food Science and Technology Abstracts. Table 2-1 provides a list of the search terms used by database. After reviewing the abstracts retrieved in these searches it was determined that the second set of search terms did not provide additional literature that was relevant to the topic studied. Therefore, only the first set of terms was used when searching additional databases, which included New York Academy of Medicine Grey literature Report, NTIS, AgEcon, and CAB Abstracts (Appendix A details the strategy for each search conducted by database).

| Set | Search Terms |

| 1 | ("front of package nutrition label" or "FOP label" or "front of package label" or "shelf-labeling") and: ("Consumer" or "Consumer response" or "effective" or "design" or "nutrition" or "producer" or "retailer") Years included: 1990 present Language: English Databases searched: PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, CHINAHL, Business Source Corporate, PsycINFO, AGRICOLA, Food Science and Technology Abstracts, New York Academy of Medicine Grey literature Report, NTIS, AgEcon, and CAB Abstracts |

| 2 | ("front of package nutrition icon" or "front of package nutrition logo" or "front of package labeling scheme" or "Signposting" or "Principle Display Panel") and ("Consumer" or "Consumer response" or "effective" or "design" or "nutrition" or "producer" or "retailer") Years included: 1990 present Language: English Databases searched: PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, CHINAHL, Business Source Corporate, PsycINFO, AGRICOLA, Food Science and Technology Abstracts |

Results of the searches were saved in EndNote and duplicate articles were removed. We also entered into EndNote the bibliographies and abstracts of literature obtained during the proposal writing and references provided by ASPE after the kick-off meeting.

We initially identified a total of 190 articles in our searches. Two researchers independently reviewed each abstract. In situations where an abstract could not be obtained and the article title was relevant to the topic studied, we retrieved the article to determine whether it was relevant. We initially deemed 106 articles to be potentially relevant and retrieved them. Articles not retrieved for review discussed related but not directly relevant topics such as organic versus nonorganic food package labeling, country-of-origin labeling, and restaurant nutrition labeling.

To supplement our database searches and to retrieve additional grey literature, we also reviewed DHHS, FDA's Front-of-Pack and Shelf Tag Nutrition Symbols docket solicitation (DHHS, FDA, 2010). Additional articles identified by the experts we interviewed or identified in references to the documents our searches identified were also included, as were five additional articles and letters of response to the docket solicitation in the fall of 2010. In total, we identified 197 articles and documents, which after review for relevance by two independent researchers, yielded 111 articles that were reviewed for this report. Table 2-2 shows the identified articles by category and their corresponding counts.

| Category | Count |

| a Fourteen of the 69 studies were review articles. | |

| Total articles identified in initial searches | 190 |

| Articles identified from experts interviewed | 5 |

| Letters of response to docket identified after memorandum report | 2 |

| Total Identified | 197 |

| Nonrelevant articles (e.g., labeling of point of origin; organic/nonorganic) | 84 |

| Articles reviewed | 111 |

| Commentary/review articles | 69a |

| Empirical studies | 42 |

| FOP articles on consumer response: | 28 |

| Focus groups and in-depth interview studies | 4 |

| Nonexperimental studies (e.g., surveys) | 12 |

| Experimental studies | 12 |

| FOP articles on producer/retailer response | 4 |

| Shelf-labeling articles | 8 |

| Responses to docket solicitations on consumer/producer response | 2 |

We created evidence tables from empirical experimental and nonexperimental studies we identified in journal articles and in the grey literature. Two researchers independently reviewed these studies to abstract important information regarding the study design (including FOP labels used), sample population, and outcome measures. We assessed and compared the quality of studies on a 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest) scale using the criteria in Table 2-3. Studies that were scored and are presented in evidence tables provided empirical quantitative data. Other relevant studies using only qualitative methods or studies found in commentary and review articles with limited information on research methods are discussed in Section 5 but were not included in the evidence tables. Studies in the evidence tables are sorted by date (earliest to latest) and author's last name alphabetized. Higher scoring studies received greater emphasis in the Section 5 and 6 discussions.

| Quality Criterion | Score |

| 1. Comparison or control group | 1 = yes, 0 = no |

| 2a. Randomization: Randomized assignment of intervention and controls | 0.5 = yes, 0 = no |

| 2b. Randomization: Probability-based selection of sample | 0.5 = yes, 0 = no |

| 3. Adequate sample size (i.e., 30+ per group) | 1 = yes, 0 = no |

| 4. Statistical control for confounding factors | 1 = yes, 0 = no |

| 5a. Clear description of the stimulus/or intervention and control condition | 1 = yes, 0 = no |

| 5b. Peer review status | Subtract 0.5 point if the study had not gone through peer review |

Many of the experimental studies of consumer response involved posttest-only comparisons reported in terms of means and statistical significance (some, but not all, of these studies report the standard deviations). One challenge is that the means are often based on Likert-type rating scales. This makes it difficult to compare findings across studies in a way that clearly communicates the magnitude of effects.

2.2 Interviews with Experts

RTI initially compiled a list of 15 potential experts for discussions on FOP labeling, incorporating suggestions of experts from ASPE and FDA. RTI selected experts from nutrition and public health, industry, consumer behavior and advocacy, marketing, and economics. We assigned a priority level to each expert for scheduling purposes. Questions for the discussions were developed based on the framework for the scan on consumer, producer, and retailer responses to FOP labeling (Appendix B). The questions pertained to the experts' opinions on key issues for consumers, producers, and retailers with respect to FOP and shelf labeling. A draft of discussion questions was reviewed and approved by ASPE and FDA. We selected seven experts and conducted 30- to 60-minute interviews via telephone. One of the experts, Dr. Wills, invited a colleague (Dr. Storcksdieck) to join the interview. The experts interviewed are listed in Table 2-4.

| Name | Country | Area of Expertise | Association with an FOP System |

| NA = Not applicable. | |||

| Scot Burton | USA | Marketing | NA |

| Klaus Grunert | Denmark | Consumer behavior | NA |

| Janet Hoek | New Zealand | Marketing | NA |

| David Katz | USA | Nutrition/public health | NuVal |

| Jaap Seidell | Netherlands | Nutrition/public health | Choices Programme |

| Lisa Sutherland | USA | Consumer behavior/industry | Kellogg's (formerly with Guiding Stars) |

| Josephine Wills and Stefan Storcksdieck | Belgium | Consumer behavior/advocacy/policy | NA |

3. IDENTIFICATION OF ISSUES

This section reviews the issues regarding FOP nutrition labels identified in our review of the literature and our discussions with experts. We organize these issues in terms of issues from the public health perspective, the consumer perspective, and the producer and retailer perspective. Then to provide a fuller context for this report, we briefly describe the experience of other countries in implementing FOP nutrition labeling systems.

3.1 The Public Health Perspective

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 68% of American adults are overweight or obese (Flegal, Carroll, Ogden, & Curtin, 2010). Obesity rates have tripled in children since 1980, and currently, 32% of children aged 2 to 19 years old are overweight or obese (at or above the 85th percentile of BMI for age) (Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, Lamb, & Flegal, 2010). Obesity increases the risk of chronic diseases, including coronary heart disease, stroke, certain forms of cancer, and type 2 diabetes. It is estimated that obesity accounts for 10% of all medical spending and $147 billion per year (Finkelstein, Trogdon, Cohen, & Dietz, 2009).

To help reduce the incidence and prevalence of morbidity and mortality associated with obesity and chronic diseases, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 recommends Americans reduce their overall caloric intake and limit their intake of saturated and trans fatty acids, cholesterol, added sugars, salt, and alcohol, which are the nutrients associated with higher risks of chronic diseases (DHHS & USDA, 2005). Several studies have shown that following this recommended diet could save lives. For example, one study estimated that adopting desirable dietary behaviors could reduce rates of mortality from any cause in women and men aged 45 years or older by approximately 9 to 16%, respectively (Kant, Graubard, & Schatzkin, 2004). In addition, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute estimated that reducing sodium levels in processed and restaurant foods by 50% could save 150,000 lives per year (Havas, Roccella, & Lenfant, 2004). Excess consumption of sodium leads to increased risk of hypertension, which is associated with increased rates of heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease. Since processed foods are a significant source of sodium in the U.S. diet, it is particularly important that information on sodium levels be readily available on product packages. It has also been found that disclosing the number of grams of trans fatty acids per serving on the NFP could prevent from 600 to 1,200 cases of coronary heart disease and prevent from 240 to 480 deaths annually (DHHS, FDA, 2003).

As the obesity epidemic suggests, an alarming number of consumers struggle to make informed and healthy food choices. Improved food labeling could help consumers construct healthier diets and reduce their risks of chronic diseases. To combat obesity and overweight, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently concluded that FOP labeling should display calorie information and serving sizes in familiar household measures and highlight saturated and trans fatty acids and sodium (IOM, 2010). According to IOM (2010), such an FOP labeling scheme could help consumers make healthier choices and encourage food manufacturers to reformulate less healthy products.

3.2 The Consumer Perspective

In an extensive review of consumer food labeling research, Grunert and Wills (2007) concluded that consumers are generally aware of the overall link between food and health and are interested in receiving nutrition information on food packages. Approximately one-half of U.S. consumers report using the labels that list ingredients and nutrition information on food packages when buying a product for the first time according to the 2008 Health and Diet Survey conducted by FDA (Choinière & Lando, 2010). Other estimates may be lower than this; for example, in a six-country European survey, only 16.8% of consumers reported looking for nutrition information when they shopped (Grunert, Fernández-Celemín, Wills, Storcksdieck genannt Bonsmann, & Nureeva, 2010). Nonetheless, other studies have found that using nutrition labels can contribute to healthier consumption. Hersey et al. (2001) found that low-income shoppers who reported that they "always or almost always read the nutrition label" consumed less fat than those who did not read the NFP. Many studies, however, have also shown that some consumers, particularly older adults and consumers with lower levels of education and income, have difficulties using or interpreting food labels accurately, mainly because of the complexity of information and/or the associated quantitative tasks involved. According to Levy and Fein (1998), the majority of consumers do better making comparisons of products with high low ratings than numerical scores. Levy and Fein (1998) and other researchers (Grunert & Wills, 2007; Wansink, 2003; Williams, 2005) also found that consumers prefer short FOP labels to back-of-package labels (i.e., the NFP). Hence, a simplified FOP label that summarizes key nutrition information could reduce confusion and help consumers choose healthier products in less time and with less nutritional or mathematical knowledge (Möser, Hoefkens, Van Camp, & Verbeke, 2010).

Relatively little research exists on the impact FOP labels have on reported and actual food purchasing and dietary behaviors (Smith, Stephen, Dombrow, & Macquarrie, 2002). Most research concerning FOP labels has occurred outside the United States but likely provides some valuable lessons for what may be most helpful for American consumers. In the United Kingdom (UK) and other European Union (EU) countries, consumers like FOP labels and see them as a useful supplement to current food labels (Grunert & Wills, 2007; Navigator, 2007). Currently, there is no clear consensus among consumers on the preferred FOP labeling scheme, most likely because consumers look for different things on labels and have different priorities (e.g., price vs. nutrition) (Grunert & Wills, 2007). However, some research found that consumers use and understand the traffic light (TL) FOP labeling system, in use in the EU countries, which uses red, amber, and green color codes to indicate whether nutrient amounts are "high," "medium," or "low," better than other FOP labeling schemes (Grunert & Wills, 2007). Research also indicates the Guideline Daily Amounts (GDA) FOP label, employed in the UK and New Zealand, which uses the percent daily value amounts similar to those used in the NFP, is mostly used and understood by a select fewthose who already use food labels and/or those who want more detailed nutrition information (Gorton, 2007).

3.3 The Producer and Retailer Perspective

Nutrition labels and food packaging are the interface between food manufacturers and consumers (Gorton, 2007). According to an interview with Dr. Lisa Sutherland of Kellogg's, FOP labels are traditionally part of a food manufacturer's marketing scheme, a way for food manufacturers to differentiate and sell their products. In their response to Docket No. FDA-2010-N-0210, Mars, Inc. (U.S.) stated, "numerous food manufacturers have voluntarily implemented GDA FOP labels on their products because they are [an] effective tool to communicate nutrition information to consumers at the point of purchase. Compared with other FOP labeling schemes, GDA FOP labels are preferred [by food manufacturers] because they are easy to use, are effective, and are already widely adopted in the food industry globally" (Mars, Inc., 2010).

In the UK, 90 members of the food industry, including 83 food manufacturers, have introduced GDA FOP labels on over 20,000 food product lines, or 50% of all UK retail food and beverage packages (http://www.gdalabel.org.uk). Food manufacturers' data comparing consumer use and understanding of GDA FOP labels versus other FOP labeling schemes, like the TL labeling scheme, are extremely limited publically, making it unfeasible to conclude why food manufacturers prefer the GDA labeling scheme over other FOP labeling schemes, particularly the TL labeling scheme.

According to the experts that RTI interviewed for this study, food manufacturers prefer the GDA FOP labels over the TL labeling scheme because they do not want to communicate negative information about their products (i.e., red TLs) or have consumers interpret their products as unhealthy because their sales may suffer if their products display labels with more red lights than green lights. Similarly, a spokesperson for The Food Commission stated in a 2006 issue of New Nutrition Business (NNB), "The food industry simply does not want a color-coded labeling scheme that will force them to put a red sticker on a great number of foods. The food industry is terrified of losing sales [from products] with red dots" (p. 8). Per their response to Docket No. FDA-2010-N-0210, the Food Marketing Institute (FMI) opposes an FOP labeling scheme that employs colors with negative connotations; they believe such colors are "akin to a warning label" (FMI, 2010).

Yet Becky Lang, a nutritionist at Teeside University, stated in NNB (2006), "If the entire cereal aisle is plastered with red dots, it may force the food industry to address the formulation of foods and make healthier product choices" (p. 8). Möser et al. (2010) and the experts that RTI interviewed also agreed that FOP labeling schemes, like the TL labeling scheme, could motivate food manufacturers to reformulate and improve their products because food manufacturers are very concerned about placing negative information on their products. Möser et al. (2010) and Rubin (2004) concluded that a mandatory FOP labeling scheme could eliminate food products with unfavorable characteristics from the market.

Comments received from the food industry regarding Docket No. FDA-2010-N-0210 (DHHS, FDA, 2010) somewhat varied. Most food manufacturers, retailers, and organizations support a fact-based approach FOP labeling scheme that highlights at a minimum calorie information and is grounded on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. Although it is apparent that most food manufacturers use and, therefore, support a GDA FOP labeling scheme, some members of the food industry are not opposed to a TL labeling scheme, and other food industry members favor an FOP labeling scheme based on a nutrient profiling system, like NuVal. A few manufacturers, such as TreeNut and Paramount Farms, a producer of pistachios and almonds, advocate an FOP labeling scheme that highlights good and bad types of fat by rating healthy mono- and polyunsaturated fats instead of total fats.

Several food manufacturers stressed that FDA should consider package sizes and shapes (e.g., by exempting small packages), different package materials, printing processes (e.g., use of color and time), and package location when considering an optimal FOP labeling scheme so that the labels do not interfere with a manufacturer's ability to sell and market [their] product. Several members of the food industry also stressed in their responses the need for a public education campaign to help consumers identify and use FOP labels.

A few food retailers promote their own shelf-tag labels. For example, Stop and Shop/Giant disclosed that sales of shelf-labeled products in eight categories increased significantly in test stores where a shelf-tag labeling program was implemented over control stores. They concluded that "shelf tags are effective in providing consumer[s] with nutrition information and can help them make better choices" (Ahold, USA, Inc., 2010). On the other hand, the FMI recommends against a voluntary shelf-tag labeling program in their responses to Docket No. FDA-2010-N-0210 (DHHS, FDA, 2010) because they believe "such an effort would be counterproductive as it would stifle vigorous competition occurring among supermarkets in providing nutrition information to consumers. The use of shelf tags has increased dramatically among supermarkets in recent years and is an important point of differentiation for retailers" (FMI, 2010).

In the interviews that RTI conducted with experts, most interviewees believe that retailers would potentially benefit from their own shelf-tag labels because using them would differentiate their products and stores from their competitors, increase store traffic, and promote customer loyalty. A few experts mentioned that they have heard testimonials from retailers that shelf-tag labeling programs increased profit margins and shifted consumer purchasing of healthier products. These experts have also heard testimonials that food manufacturers have reformulated some products to achieve better "scores" from the shelf-tag labeling programs.

3.4 The International Experience

To provide a clearer context for understanding issues regarding FOP labels, this section briefly describes the implementation of FOP nutrition labels in other countries: Sweden, the UK, the Netherlands, and Australia and New Zealand.

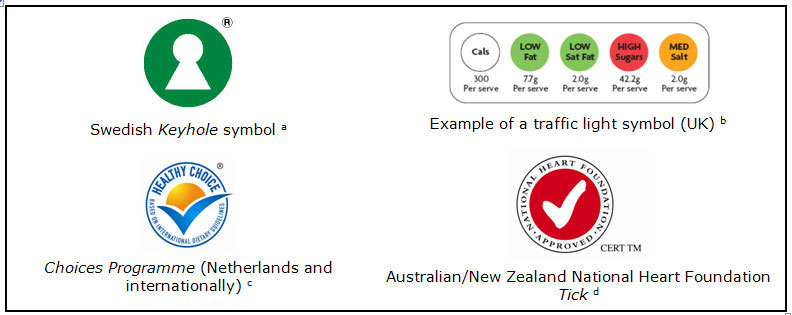

3.4.1 Sweden

In 1989, Sweden's National Food Administration (NFA) established the Keyhole symbol to help consumers identify healthier food options within product categories (see Figure 3-1). The Keyhole symbol is a voluntary FOP label currently used in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden on prepackaged foods, fresh or frozen fish, and fresh or frozen fruits and vegetables, as well as restaurant menus and store recipe leaflets. The Keyhole symbol assures a product has limited amounts of total fat, saturated and trans fatty acids, total or added sugar, and salt and has a minimum amount of fiber. For example, dairy products with the Keyhole symbol contain less fat, salt, and sugar than corresponding products not labeled with the symbol. Although NFA sets the labeling criteria for 25 product groups for the Keyhole symbol, food manufacturers are responsible for ensuring food bearing the symbol conforms to NFA's regulations. Manufacturers are not charged to use the Keyhole symbol but are responsible for its promotion, and their products bearing the symbol are subject to review by NFA at any time.

Figure 3-1. FOP Symbols Used Internationally

aKeyhole symbol reprinted with permission from the National Food Administration, Sweden.b TL symbol reprinted with permission from the Food Standards Agency, UK.cChoices logo reprinted with permission from the Choices International Foundation, Belgium.d The National Heart Foundation Tick reprinted with permission from the National Heart Foundation of Australia.

aKeyhole symbol reprinted with permission from the National Food Administration, Sweden.b TL symbol reprinted with permission from the Food Standards Agency, UK.cChoices logo reprinted with permission from the Choices International Foundation, Belgium.d The National Heart Foundation Tick reprinted with permission from the National Heart Foundation of Australia.

The Keyhole symbol was introduced by food manufacturers during the 1980s as part of a regional intervention project in northern Sweden to reduce the prevalence of coronary heart disease. One of the primary reasons NFA established the Keyhole symbol nationally was to stimulate food manufacturers to reformulate products and develop healthier products. Within 3 years of its introduction, consumer knowledge of the Keyhole symbol and consumer intake of low-fat and high-fiber foods increased (Larsson, Lissner, & Wilhelmsen, 1999). As reported by the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) in a petition to FDA, ICA, a major Swedish retailer, found sales of food products bearing the Keyhole symbol rose 15% in 2003 and 2004 (CSPI, 2006). However, Lobstein and Davies (2008) noted some drawbacks of the Keyhole symbol. They believe the symbol may not be applied uniformly to identify foods consumers should eat more of, like fruits and vegetables, and might be misunderstood by consumers to mean that food products bearing the symbol are recommended as an important and valuable part of a healthy diet, which in some cases they are not.

3.4.2 United Kingdom

In 2005, the UK's Food Standards Agency (FSA) adopted the TL labeling scheme (see Figure 3-1) to help consumers assess the levels of nutrients within a single food product and compare food products by using color-coding to help ascertain whether specific nutrient levels for fat, saturated fat, sugar, and salt fall under government definitions of high (red), medium (yellow), or low (green). FSA recommended applying the TL labeling scheme to seven categories of composite, processed foods and urged food manufacturers and retailers to voluntarily use the TL labeling scheme on such convenience foods as ready-to-eat meals, breakfast cereals, pizzas, sandwiches, burgers, and pies. By 2008, eight major food retailers, 26 food manufacturers, and one restaurant chain voluntary displayed the TL labeling scheme on 40% of all composite processed foods in the UK (Kondro, 2008).

Although several food companies, particularly retailers, widely adopted the TL labeling scheme, especially for store-brand items (Lobstein & Davies, 2008), a consortium of food companies disregarded FSA's recommendation and continued using GDA FOP labels on food products in the UK. GDA FOP labels typically display, without color-coding, the percentage recommended daily intakes for salt, sugar, fat, saturated fats, and calories. In their March 2006 issue, NNB reported there seems to be a "clear agreement across the food industry that GDAs are the most appropriate basis for providing important nutrition information to consumers" (p. 7). Additionally, some food retailers in the UK developed their own versions of FOP labels. For example, Sainsbury's, the third largest chain of supermarkets in the UK, developed their own TL labeling scheme, known as the Wheel of Health, which is a color-coded nutrient pie chart, and Tesco, the grocery market leader in the UK, developed its own GDA FOP label that uses color to identify nutrients, not nutrient levels (e.g., pink indicates sugar and yellow indicates salt).

Both Sainsbury's and Tesco reported increased sales of healthier products after they introduced each of their own FOP labeling schemes in their stores. Not only did Sainsbury's say their Wheel of Health significantly increased sales patterns but also stimulated manufacturers to reformulate their products to achieve healthier profiles (The Food Magazine, 2006; British Retail Consortium, 2009). Tesco reported that sales of healthier products increased by 80% (Green, 2006). Consumer research experts, however, caution the evidence was more anecdotal because neither Sainsbury's nor Tesco controlled for other factors (e.g., marketing promotions and/or discounts) or specified study details (Grunert & Wills, 2007). Also, Lobstein and Davies (2008) noted that more detailed evaluation is needed to show whether Sainsbury's Wheel of Health results in long-term behavior changes and sustains improvements in product reformulation.

In July 2006, Which?, a consumer organization in the UK, found 73% of UK consumers were confused by the variety of different FOP labels found on food products. Based on the same study results, consumers were able to use the TL labeling scheme correctly and found it easy to understand and quick to use. Compared with GDA FOP labels, the TL labeling scheme led to a significantly higher level of correct comparisons between products and provided consumers with more useful information to assess nutrition levels in individual products. The same study also found only a minority had a very good understanding of how to use GDA FOP labels. Another study found consumers had difficultly assessing and comparing the nutrients levels within a single food product and between food products using GDA FOP labels mostly because of different portion sizes (Lobstein, Landon, Lincoln, Ash, & Presso, 2007).

In a 2006 poll conducted by Harris Interactive, 46% of consumers reported they found different FOP labels confusing and would prefer to see one labeling scheme used on all food products; however, 39% of consumers believed the different FOP labels made sense in their own right. The poll also revealed that 40% of consumers believed FOP labels help them make healthier food choices, and 65% of consumers found the TL labeling scheme most helpful in determining whether a product was healthy. However, 45% of consumers polled said FOP labels had no effect on their purchasing decisions (Green, 2006).

In 2010, FSA released a report of a comprehensive 2009 study, including an independent review of consumer labeling research by Dr. Klaus Grunert, to assess several FOP labeling schemes (FSA, 2007). The report concluded that consumer use and understanding of FOP labeling could be improved if a single FOP labeling scheme were used that combined several FOP labeling schemes; that is, one scheme that incorporated both the words "high," "medium," and "low," and GDAs with or without TL color-coding. Based on the report, FSA made several changes to the TL labeling scheme, which included adding the words "high," "medium," and "low," and calories per portion to the scheme.

3.4.3 The Netherlands

In the Netherlands, an independent scientific committee of nutrition and food scientists developed the Choices logo (see Figure 3-1), which is assigned to food products that contain lower levels of sodium, added sugar, saturated fat and trans fatty acids, and energy and increased levels of fiber compared with similar products within the same product category. The Choices logo is not supported by a single authority but by a foundation of food manufacturers, retail and food service organizations, the Netherlands Nutrition Center, and nutrition scientists, and it is conditionally endorsed by the Dutch government. The Choices logo can be found on a variety of brands in many supermarket chains, worksite cafeterias, and other food service locations across the Netherlands, but, more specifically, on the following 10 food categories: vegetables and fruits, sources of carbohydrates, sources of protein (e.g., meat, fish, eggs, meat substitutes), dairy products, oil and fats, ready-to-eat meals, soups, sauces, snacks, and beverages. At its conception, a mass media campaign was developed to communicate the meaning of the Choices logo to consumers.

As of June 2008, more than 100 food manufacturers had joined the foundation, and the Choices logo was assigned to approximately 2,100 packaged food products and 600 fresh fruits and vegetables. In 2009, exposure to Choices logo significantly increased from 33% to 88% in its first year (Vyth et al., 2009). In a supermarket study, researchers found that consumers who are more weight and health conscious (i.e., pay more attention to their weight and/or look at nutrition information on food packages) actually do purchase more products with the Choices logo. However, the study also found that participants who reported having intentionally purchased products with the Choices logo had actually purchased more products with the logo than participants who reported not purchasing products with the logo intentionally (p 0.01) (Vyth, Steenhuis, Vlot, et al., 2010).

Currently, the Choices International Foundation has secured the endorsement of local authorities, scientists, nongovernmental organizations, and industry to support the logo in nine countries.

3.4.4 Australia and New Zealand

The Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) is the governmental body responsible for developing food standards for Australia and New Zealand. Since 2002, FSANZ has required the nutrition information panel (NIP) to be displayed on food products, but consumer research indicates that consumers do not understand how to use the NIP to make healthy choices (Gorton, 2007). Currently, FSANZ is investigating whether an FOP labeling scheme would be an effective health strategy to guide consumer choice toward healthier food options and whether it should be voluntary or mandatory. According to research, most New Zealand consumers prefer the TL labeling scheme over the GDA FOP labeling scheme. The same research found that the TL labeling scheme was well understood across multiple consumer groups, including different ethnicities, races, education levels, and infrequent label users (Gorton, 2007).

The Heart Foundation in Australia and New Zealand implements the Tick program, a national public health initiative encouraging food companies to reformulate their products by meeting nutrition criteria and in return are able to display a certified trademark (the Tick logo) on food packaging and promotional material (shown in Figure 3-1). Tick criteria are based on national criteria for saturated fat, trans fat, salt, energy, fiber, and whole grains. The Tick program uses a panel of nutrition experts who research, approve, and set nutrition standards to specific food categories; currently there are 60 food categories. The Tick logo is on approximately 1,100 food products from 80 food companies. Each product that applies for the Tick is independently tested to verify if it meets standards. The Heart Foundation conducts random testing to make sure Tick products continue to comply with the standards. The Heart Foundation regularly reviews these nutrition criteria, changing them in a stepwise manner over time, so that the standards are always challenging manufacturers to produce Tick products that are healthier.

Research has shown the Tick logo acts as a "nutrient signpost" for consumers and has significantly influenced product reformulation (Vyth et al., 2009). Consumer awareness and use of the Tick logo is also high. As reported by Smith et al. (2002), two studies showed that 51% of women and 31% of men stated they had bought food with the Tick logo, and 68% of women and 55% of men stated that the presence of the Tick logo would persuade them to change brands. Also, according to Young and Swinburn (2002), many Tick products have either been specifically formulated or reformulated to meet Tick guidelines, particularly guidelines for fat and sodium. The Tick program has seen 61%, 26%, and 11% in average sodium reductions for cereals, breads, and margarine, respectively (Smith et al., 2002). As a result of the Tick program, 235 tons of salt have been removed from the Australian food supply annually (Williams, McMahon, & Boustead, 2003).

4. SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS WITH EXPERTS

In this section, we summarize the findings from the telephone interviews with seven experts regarding FOP labeling conducted in October 2010. Appendix B contains the discussion guide used in the interviews. The experts represent the areas of nutrition and public health, industry, consumer behavior and advocacy, and marketing. We summarize the findings by each of the following topic areas: (1) consumer response to FOP labeling, (2) producer response to FOP labeling, (3) retailer response to FOP labeling, (4) public health issues regarding FOP labeling, and (5) criteria for developing and assessing FOP systems. In general, the information provided by the experts corroborates the results in the literature review discussion in Section 5, as the experts are aware of the same literature. However, most experts emphasized the need to take the research to the "real-world" setting (i.e., studying consumer use and understanding in the supermarket and impacts on diet and health).

4.1 Consumer Response to FOP Labeling

Most experts agreed that consumers notice the NFP but not all consumers use or understand the information, particularly ethnic minorities and individuals with lower education levels and incomes. A few experts also noted that younger adults understand food labels better than older adults, but older consumers look at food labels more often. Most experts noted that consumers who are more educated and/or more health conscious are more likely to use and understand the NFP and other labeling features compared with other consumers. Most experts agreed, though, that most consumers want nutrition information available to them even if they do not use or understand it.

Most experts agreed that FOP labels could allow consumers to more easily compare food products and make healthier choices as long as the labels are conspicuous, consistent, and simple; promoted and created by a trustworthy source; and decrease the amount of time and knowledge it takes to make healthy decisions. As a member in the Keystone Food and Nutrition Roundtable, Dr. Lisa Sutherland learned that consumers look at food packages for a total of 9 seconds based on an eye-tracking study conducted to evaluate the Smart Choices program. She concluded FOP labels would be most noticeable if they appeared on the top left or top right of packages because people naturally read from top to bottom and left to right.

Based on their research, some experts found that FOP labeling schemes neutralized the gap in disparities among different population segments. For example, Dr. Sutherland mentioned that the GDA FOP label works for low-income populations because it takes away the "subjectivity," that is, the GDA label provides direct nutrition information rather than information that must be interpreted. Dr. Janet Hoek in New Zealand observed that TL labels neutralize the disparities normally found among different income and education levels as well as differences between highly motivated individuals (nutrition-information seekers) and less motivated individuals. Dr. David Katz believes nutrient profiling systems, like NuVal, eliminate real disparities among subgroups because "everyone can count to 100." Dr. Klaus Grunert believes there are no significant differences between different population segments in consumers' abilities to select the healthiest product within the same food category; however, he believes that most consumers have a more difficult time identifying the healthier product across food categories. Dr. Grunert, also mentioned, as did other European experts, that consumers from EU countries that have nationally known health messages and/or educational campaigns, like the UK, notice, use, and understand FOP labels more than other Europeans, particularly Eastern Europeans; currently 27% of UK consumers and 9% of French consumers notice FOP labels. Notably, Dr. Jaap Seidell in the Netherlands observed that low-income consumers consider price first, then convenience, taste, and finally healthfulness of a product. He believes the most effective FOP labeling system would consider all these factors. For example, if the healthiest products were less expensive and still tasty, then consumers, specifically those with lower incomes, would be more motivated to buy the healthiest products.

Based on a consumer research pilot study for FOP labels and other research he has conducted regarding calorie disclosures on restaurant menu boards, Dr. Scot Burton concluded that in order for FOP labels to make an impact on consumers the labels have to disconfirm consumers' expectations about the healthfulness of a product. For example, if someone expects a product to be higher/lower in a positive/negative nutrient than it actually is (based on the label), the FOP label is more likely to influence their purchase decision. More simply, if a consumer thinks a product is unhealthy but reads the FOP label and finds it is healthy, then the consumer is more likely to buy the product (and vice versa). If FOP labels simply confirm previous expectations (or prior beliefs) about product healthfulness, the FOP will have little influence.

4.2 Producer Response to FOP Labeling

Experts agreed that food manufacturers use FOP labels to market their products. According to Dr. Sutherland, FOP labels are traditionally part of a food manufacturer's marketing scheme, a way for food manufacturers to differentiate and sell their products. Hence, as Dr. Katz stated, "food manufacturers use FOP labels to accentuate the positives and ignore the negatives." He believes the FOP labels developed by food manufacturers provide some truth, but not the whole truth, about the nutrition of their products. For example, food manufacturers may label their products as "a good source of essential nutrients," but the products may also be high in fat. He believes the Smart Choices program was a failure because it was designed by manufacturers to help them differentiate and sell their products; thus, he believes that food manufacturers should not own an FOP labeling system. On the contrary, he believes a good, independent FOP labeling system would encourage competition among the food manufacturers and reformulation, which would ultimately lead to consumers purchasing more nutritious products within product categories.

Many experts agreed that food manufacturers prefer the GDA FOP labels over the TL labeling scheme because they do not want to communicate negative information about their products (i.e., red TLs) or have consumers interpret their products as unhealthy because their sales may suffer if their products are labeled with more red lights than green lights. A few experts also noted that food manufacturers who are currently using the GDA FOP labels would be opposed to adopting a different FOP labeling scheme because of cost and time to make changes to their food packages. Dr. Sutherland said that it can take up to 2 years to make changes to a food package. In contrast, a few experts believe that a few food manufacturers (e.g., those with products with low amounts of negative nutrients) would prefer the TL labeling scheme over the GDA FOP labels because it would make their products look more favorable.

Most experts agreed that FOP labeling schemes, like the TL labeling scheme, could motivate food manufacturers to reformulate and improve their products because food manufacturers are very concerned about placing negative information on their products, and they want consumers to buy their products. Comparatively, Dr. Burton found in his own research that requiring the disclosure of calorie information on restaurant menu boards encouraged some restaurant chains to undertake product reformulation or introduce new products (e.g., grilled chicken at Kentucky Fried Chicken).

Some experts believe that it may be too costly or difficult for some food manufacturers to reformulate their products. For example, Drs. Josephine Wills and Stefan Storcksdieck reported that in some cases a food manufacturer may be more likely to introduce a new product than reformulate an existing product because reformulation would affect product qualities like taste or texture. Dr. Seidell mentioned that the Netherlands uses a step-wise approach to gradually reduce the amount of negative nutrients (e.g., sodium) incrementally to avoid negative consumer reaction to major product changes.

4.3 Retailer Response to FOP Labeling

Most experts agreed that food retailers would potentially benefit from using a shelf-tag labeling scheme. By offering existing and new customers nutrition information via shelf tags, food retailers would differentiate their products and stores from their competitors, increase store traffic, and promote customer loyalty, which would ultimately increase food retailers' market shares and profit margins. Dr. Sutherland, one of the scientists behind Hannaford's Guiding Stars, mentioned that the original purpose of the program was to bring in secondary shoppers and convert them to primary shoppers by "adding value to their shopping" experience. By adapting the shelf-tag labeling scheme to an FOP labeling scheme and using FOP labels on private brands, many experts agreed that food retailers' store brand products would overshadow larger food manufacturers' products, possibly motivating large food manufacturers to reformulate their products to compete with less expensive private brands. However, Dr. Sutherland noted that although Hannaford supermarkets in the United States saw more customers in their stores after the introduction of the Guiding Stars program, she stressed that it took a lot of money and time to implement the program in their stores, and "it was a nightmare for store managers."

A few experts said that they have heard testimonials from retailers that shelf-tag labeling programs have led to increased profit margins and shifts in consumer purchasing to healthier products. For example, Dr. Katz, the principal inventor of the Overall Nutritional Quality Index used in the NuVal nutrition guidance program, is drafting a manuscript that concludes "consumers are purchasing more nutritious products within product categories." Experts also mentioned that food manufacturers have reformulated some products to achieve better "scores" from the shelf-tag labeling programs. For example, Dr. Sutherland mentioned that large food manufacturers inquired about getting more stars for their products after the launch of the Guiding Stars program; most manufacturers were interested in how they could get more stars by reformulating their products to attain lower amounts of negative nutrients (e.g., fat or sodium). Hence, Drs. Katz and Sutherland believe a shelf-tag labeling system would be the most advantageous way to provide consumers with nutrition information because retailers would be responsible for "scoring" every product on their shelves, and all consumers look at the shelf price tag. However, Drs. Katz, Sutherland, and Burton noted that consumers need nutrition information both at the point of purchase and at home to make optimal dietary decisions.

A few experts mentioned they read about Tesco's reported increased sales of healthier products in the UK after the introduction of Tesco's FOP labeling scheme and agreed the evidence was anecdotal based on lack of specific details, including lack of controls for other factors (i.e., marketing promotions and/or discounts). Drs. Wills and Storcksdieck also mentioned another paper that found no difference in sales of healthier products 4 weeks before and after the introduction of the TL labeling scheme in the UK (Sacks, Rayner, & Swinburn, 2009). Based on randomized trials in catering institutions and supermarkets, Dr. Seidell found FOP labels did not have a large effect on consumer choices but found pricing and product placement in conjunction with FOP labels had a larger effect on consumer choices.

Dr. Wills suggests that studies that look at food retailers' loyalty or club card data are the key to determining whether consumers use shelf-tag labels or FOP labels to choose healthier products. She also thinks such studies could reveal indirect effects of shelf-tag labels or FOP labels, like whether consumers who buy healthy products compensate with less healthier products. On the other hand, Dr. Seidell does not believe that FOP labels alone can have a big impact on sales. He noted that it is very difficult to capture effects of FOP labels on sales data because other factors, like marketing, promotions, product placement, and discounts, have bigger impacts. He mentioned consumers may be more likely to choose healthier products if food retailers used the nutrient profile of products (indicated by a shelf tag or FOP label) to determine which products to discount or market.

4.4 Public Health Issues Regarding FOP Labeling

Although most experts underscored the importance of acquiring real-world data to understand consumers' use and understanding of FOP labels, most experts agreed that an FOP labeling scheme, specifically a uniform system, could improve the overall dietary health of consumers in the long run and help reduce the rates of obesity-related chronic diseases. Most experts, however, believed an FOP labeling scheme is just one of many components needed to combat obesity. As Dr. Katz concluded, "Better food, better diet, better health." Dr. Katz also mentioned that a retrospective study he is working on has shown that people who eat foods with higher NuVal scores have lower BMI and lower risk of cardiovascular disease and death. Many experts, though, emphasized that an educational campaign is paramount to increase consumer awareness, knowledge, and motivation to change behavior by providing consumers with the education and tools they need to improve their overall diet quality. Additionally, most experts agreed the biggest impact of an FOP labeling scheme on positive public health outcomes (e.g., healthier diets) would be the result of product reformulation to create healthier products, which would impact all segments of the population. Otherwise, Dr. Katz believes consumer behavior changes are more likely to be seen only within specific population segments (i.e., those who are concerned about their diets). Dr. Katz also mentioned that to improve public health, individuals need to control calories; however, he noted that most consumers do not want to count or reduce calories. Dr. Katz believes an FOP labeling system that would improve the overall nutrient quality of foods would also help consumers choose healthier foods with higher nutrient density and lower energy density than foods with lower nutrient density and higher energy density, which would affect satiety and result in less caloric consumption. Dr. Sutherland believes an FOP labeling scheme should incorporate serving sizes to discourage overeating.

Although the potential benefits to public health are clear, some experts agreed there could be some disadvantages to FOP labels. One unintended consequence would be if consumers choose processed foods with more positive FOP labels over naturally healthy foods, like fresh fruits and vegetables. A few experts cautioned that some consumers, particularly adolescents, men, or individuals with lower incomes, may choose a product with more "red traffic lights," or higher amounts of calories, sugar, sodium, and/or fat, because they believe the product will taste better. A few experts also believe that some consumers may overeat products with "green lights" because they think they can eat a healthy product without limits. Additionally, Dr. Katz believes that without a standard, uniform FOP labeling scheme, consumers might become confused by different schemes or formats or too much or too little information on the label. Also, he also believes that different FOP labeling schemes could cause consumer suspicion because "everyone is telling me their products are nutritious." He also believes that too much information on an FOP label could cause confusion and discourage consumers from using the information. Dr Seidell mentioned that if food manufacturers develop their own FOP labels, they could use it as a marketing tool to accentuate the positive and ignore the negative aspects of the products (i.e., low-fat products that are high in sugar and not fewer calories). Based on the research of a French colleague (Rozin, Fischler, Imada, Sarubin, & Wrzesniewski, 1999), Dr. Grunert mentioned that breaking down foods into components, as a GDA FOP label does, could "ruin food cultures" in some countries such as France that have a strong food culture and generally healthy diets.

4.5 Criteria for Developing and Assessing FOP Systems

Most experts agreed that an FOP labeling scheme should include calorie information and four nutrients already featured in most existing FOP labeling schemes (sugar, saturated fats, trans fats, and sodium), reduction of which contribute to preventing chronic disease according to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. According to Drs. Wills and Storcksdieck, consumers want to see these nutrients on food labels. They also mentioned that consumers want information on positive nutrients (i.e., fiber), but they, along with a few other experts, agreed that an FOP labeling scheme should be limited to include calorie information, fiber, sugar, saturated fats, trans fats, and sodium to reduce consumer confusion derived from too much information. Nonetheless, Dr. Sutherland believes an FOP labeling scheme should also include nutrients for which the general public is lacking (e.g., folic acid, calcium). Drs. Wills and Storcksdieck would like to see an FOP labeling scheme that distinguishes good fats from bad fats. Additionally, Dr. Hoek mentioned that no calorie information is used in FOP labeling schemes in New Zealand because consumers there do not understand how to use this information.