Family Structures and Support Strategies in the Older Population: Implications for Baby Boomers

ASPE ISSUE BRIEF

Brenda C. Spillman, Melissa Favreault, and Eva H. Allen

Urban Institute

December 2020

Link to Printer Friendly Version in PDF Format (13 PDF pages)

ABSTRACT: This brief explores the current relationships between family structure--the presence of a spouse and/or children--and caregiving arrangements when people develop long-term services and supports needs. The aim is to better understand the potential implications for increased demand on the formal long-term care system, unmet need, and reliance on Medicaid for baby boomers and future generations if fewer older adults have traditional family caregivers in the future.

This brief was prepared under contract #HHSP233201600024I between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Behavioral Health, Disability, and Aging Policy and RTI International. For additional information about this subject, you can visit the BHDAP home page at https://aspe.hhs.gov/bhdap or contact the ASPE Project Officers at HHS/ASPE/BHDAP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201; Judith.Dey@hhs.gov.

DISCLAIMER: The opinions and views expressed in this brief are those of the authors. They do not reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization. This brief was completed and submitted in March 2020.

A pressing issue for federal and state policymakers is whether demographic changes will create a shortfall of caregivers for aging baby boomers[1] (de Meijer, et al. 2013; Keefe, Légaré, and Carrière 2007; Pickard 2008, 2015; Redfoot, Feinberg, and Houser 2013). Traditionally, spouses and children have been older adults' main source of care when they develop the need for long-term services and supports (LTSS). Most LTSS is assistance with basic self-care or mobility tasks, sometimes called activities of daily living (ADLs), or household tasks, sometimes called instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). ADLS include such tasks as bathing, dressing, toileting and eating, and IADLs include such tasks as shopping, getting meals, and managing money. Baby boomers have had reduced rates of marriage and childbearing, increased rates of divorce, and rising labor force participation among working-age women compared with earlier generations (Brown and Lin 2012; Brown and Wright 2017; King and Scott 2005; National Research Council 2012).[2] Such changes may mean that spouses and children may be less available for caregiving in the future. Potential outcomes of a shortfall of these traditional caregivers include heavier demands on the formal long-term care system, greater unmet need for assistance, and increased reliance on Medicaid programs as baby boomers reach ages when functional decline is common.

This brief explores the current relationships between family structure--the presence of a spouse and/or children--and caregiving arrangements when people develop LTSS needs, defined as either receiving help with ADLs or IADLs or having difficulty performing any of these activities without help. The aim is to better understand the potential implications for increased demand on the formal long-term care system, unmet need, and reliance on Medicaid for baby boomers and future generations if fewer older adults have traditional family caregivers in the future. Findings reflect participant responses to the 2015 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), a nationally representative survey of Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 or older, regarding family structure, demographic and economic characteristics, functional status, and compensatory strategies used to accommodate declining function. The analysis sample for whom participant responses are available represents 98% of all older adults, including about 25% of nursing home residents. The analysis excludes NHATS participants representing the remaining 2% of older adults (75% of nursing home residents) who were living in nursing homes when they entered the survey, because family structure and other key information was not collected for these participants.

Who Does Not Have Children or a Spouse to Care for Them?

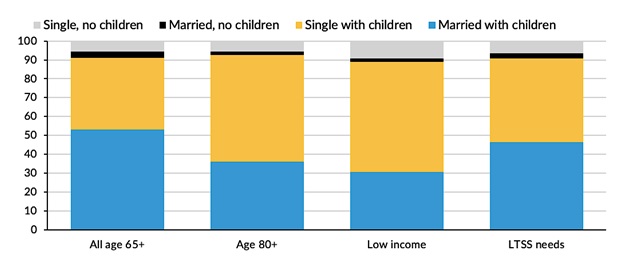

Only about 6% of people ages 65 or older have neither a spouse nor children (Figure 1). Advanced age and low income are important factors related to family structure. Relative to all older adults, both those who are ages 80 or older and those with income in the lowest quintile of the income distribution are less likely to be married (Figure 1). The proportion of older adults who have children is about 90%, regardless of advanced age or low income.

Family structure among older adults with LTSS needs is relatively similar to that for all older adults. The proportion of older adults with LTSS needs who have children is also about 90%--roughly half are married with children and roughly 40% are single with children.

| FIGURE 1. Family Structure among Adults Ages 65 or Older, by Age, Income, and LTSS Needs (%) |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015. |

Underlying this similarity in family structure patterns, however, are key differences (Table 1). Relative to all older adults, those with LTSS needs are older, more likely to have low income, and less likely to be married. Both advanced age and low income are associated with declining health and functioning, and the risk of widowhood increases with age. Those with LTSS needs are, however, no more likely than all older adults to lack both a spouse and children.

| TABLE 1. Comparison of Age, Income, and Family Structure for All Older Adults versus Those with LTSS Needs (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| All Adults Ages 65 of Older | All Adults With LTSS Need | |

| Ages 80 or older | 25.7 | 36.1* |

| Lowest income quintile | 20.1 | 27.1* |

| Married | 56.6 | 49.2* |

| Single, no children | 5.7 | 6.5 |

| SOURCE: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015. * Different from value for all people ages 65 or older; p = 0.05. | ||

Strategies to Address LTSS Needs

Older adults with LTSS needs compensate for functional decline in various ways, including receiving "informal care" from relatives or non-relatives (friends or neighbors); paying for "formal" assistance from individual paid caregivers or caregiving agencies; using assistive technology, independently or with help; and living in settings that may provide a more supportive environment and/or services, such as senior housing, independent living, or assisted living.

Informal Care

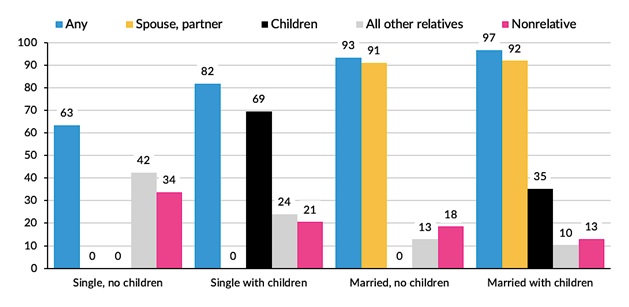

A large majority of older adults with LTSS needs receives some informal care. Spouses and children play a dominant role when they are available. When they are not, other relatives and non-relatives step up (Figure 2). Spouses or partners almost always provide care when they are present. Children care for a majority of older adults with children who lack a spouse or partner, and those without spouses or children are most likely to rely on other relatives and non-relatives.

| FIGURE 2. Percent of Older Adults with LTSS Needs Receiving Informal Care, by Caregiver Type and Family Structure |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015. |

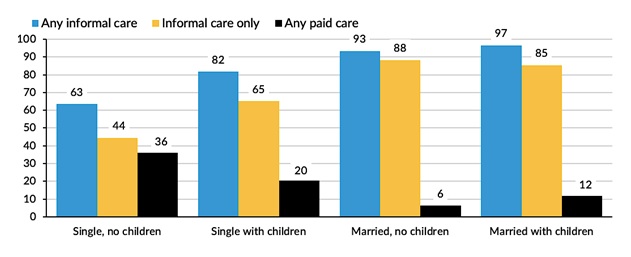

Paid Care

Regardless of family structure, a larger proportion of older adults relied solely on informal care than used any paid care (Figure 3). Paid care nearly always occurred in conjunction with informal care and was more prevalent for people without spouses or children. Thirty-six percent of those with neither a spouse nor children received some paid care, triple the prevalence for those with both a spouse and children. Only about 4% of all single older adults and 0.5% of married older adults used only paid care (not shown).

| FIGURE 3. Percent of Older Adults with LTSS Needs Using Informal and Paid Care, by Type of Care and Family Structure |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015. |

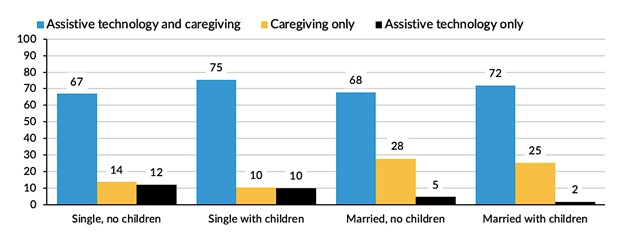

Assistive Technology

Regardless of whether they were married or had children, roughly 70% of people with LTSS needs used assistive technology, primarily in conjunction with informal or paid care (Figure 4). Assistive technology includes both personal assistive devices and home and environmental modifications. The most common types of devices are mobility aides, such as canes, walkers, or scooters, but adaptations, such as grab bars or seats in the tub or shower and raised toilet seats, are also prevalent. Single older adults were far less likely than married older adults to rely solely on informal or formal caregivers, and they were more likely to use assistive technology independently. Conversely, among married older adults, use of assistive technology without help from a caregiver was negligible.

| FIGURE 4. Percent of Older Adults with LTSS Needs Using Assistive Technology and/or Receiving Care, by Family Structure |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015. |

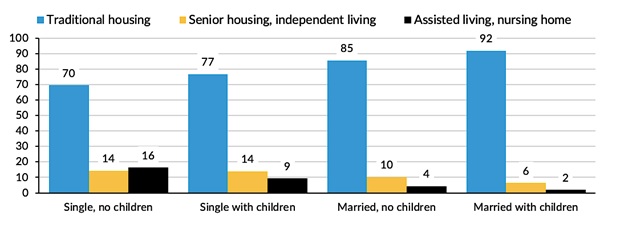

Residential Care Settings

People with LTSS needs may accommodate their needs by living in a residential setting that provides such services. A large majority of older adults with LTSS needs were living in traditional community housing--private homes or apartments (Figure 5). As noted, information on residential settings reflects only the 98% of older adults--including about 25% of nursing home residents--for whom participant responses, including family structure, were available. Only basic demographic and payment source information is available for the excluded 2% of the population, who represent 75% of nursing home residents.

| FIGURE 5. Percent of Older Americans with LTSS Needs in Various Residential Settings, by Family Structure |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015. |

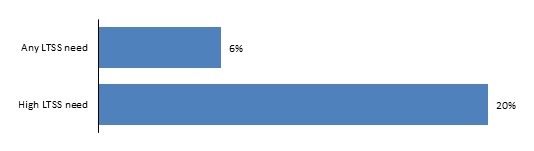

Though the share of older adults residing in settings other than traditional housing was small for all family structures, single older adults were more likely than those who were married to live in senior or retirement settings, independent living, or assisted living/nursing homes. As LTSS needs increase, the share of people in assisted living or nursing homes rises substantially. Roughly one in five people with LTSS needs has a high level of need, requiring chronic and substantial assistance with at least two ADLs or substantial supervision because of cognitive impairment. This high-need group was three times more likely to reside in assisted living or a nursing home than all people with LTSS needs (Figure 6).

| FIGURE 6. Percent of Older Adults Residing in Assisted Living or Nursing Homes, by Level of LTSS Need |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015. |

Unmet Need and Medicaid

Estimates have shown that having a spouse or child available to provide care is an important factor in how a person's LTSS needs are met. Having these potential family care resources also is important for whether an older adult experiences unmet need for care and/or relies on Medicaid to pay for care.[3] Being married, which can affect both human and economic resources available, is the most significant factor associated with lower rates of unmet need and Medicaid enrollment (Table 2).

| TABLE 2. Percent of Older Adults with LTSS Needs Experiencing Unmet Need for Care or Relying on Medicaid, by Family Structure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Family Structure | Percent with Unmet Need | Percent Relying on Medicaid |

| Single, no children | 30.9 | 34.6 |

| Single with children | 35.5 | 24.7 |

| Married, no children | 9.8 | 9.5 |

| Married with children | 27.6 | 10.6 |

| SOURCE: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015. | ||

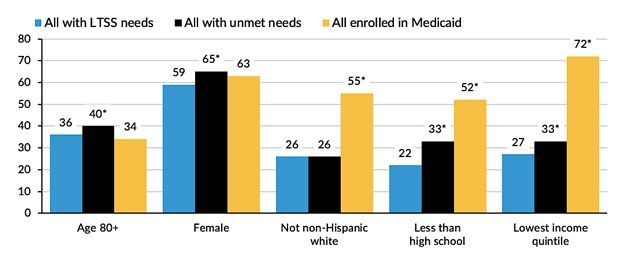

Relative to all older adults with LTSS needs, those experiencing unmet need were more likely to be ages 80 or older or female and to have less than a high school education or income in the lowest quintile (Figure 7). As expected, given financial eligibility criteria for Medicaid, Medicaid enrollment is strongly related to characteristics indicating socioeconomic disadvantage. Thus, Medicaid enrollment is far more common for people with any race/ethnicity other than non-Hispanic White, for those with less than a high school education, and for those with income in the lowest quintile, relative to all older adults with LTSS needs (Figure 7).

| FIGURE 7. Percent of Older Americans with LTSS Needs Experiencing Unmet Needs and Enrolled in Medicaid, by Characteristics Associated with Unmet Need and Medicaid Enrollment |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015. * Different from prevalence for all with LTSS needs; p = 0.05. |

Implications for the Future

As noted, a major concern raised in recent years is that reduced rates of marriage and childbearing, increased rates of divorce, and rising labor force participation among working-age women will create a shortfall of family and other informal caregivers.

The descriptive analysis in this brief provides a cross-sectional snapshot of current family situations, LTSS needs, and strategies to address the latter in a cohort including only the initial wave of baby boomers. Though demographic trends may increase the proportion of older adults without spouses or children, findings demonstrate that most of these individuals may still accommodate their LTSS needs without adverse consequences or reliance on Medicaid. Older adults without spouses or children commonly rely on care from other relatives and unpaid non-relatives. These informal caregivers may rise in importance if fewer spouses and children are available in the future.

Other demographic factors may also mitigate the potential for unmet need and reliance on Medicaid: The age distribution of the older population will get younger over the next decade as baby boomers continue to reach age 65. Caregiving needs are far more common among the eldest of the older population. Rising educational attainment, which has been associated with better health, increased longevity, and lower care needs in older age, may moderate both functional decline and the need for human assistance from traditional caregivers to address it (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2015; National Research Council 2012).[4] Recent studies have shown rising male longevity, which may mean later widowhood among baby boomers (Freedman, Wolf, and Spillman 2016; Redfoot and Pandya 2002). Our findings confirm the continuing dominant role of spouses as caregivers, so this trend may mean baby boomers will have greater spousal availability to address their LTSS needs (Redfoot and Pandya 2002).

The trend over the last 30 years toward managing functional decline with assistive technology instead of or in conjunction with human assistance has two implications for the size of the population with LTSS needs and their risk for unmet need. First, the younger, more highly educated baby boom cohorts may be better able to successfully accommodate declining function without resorting to assistance, meaning the prevalence of LTSS needs may be smaller. Second, assistive technology, including environmental modifications, may reduce the level of burden on families and other caregivers. Similarly, continuing efforts to expand publicly and privately paid services in people's homes and in alternatives to nursing homes and the growth of the market for these alternative settings may support both older adults with LTSS needs and their caregivers (Brown 2015; HCAOA and Global Coalition on Aging 2016; Houser, Fox-Grage, and Ujvari 2018; Kaye 2014).

The large size of the baby boom cohort ultimately may increase the proportion of the older population at risk of needing LTSS, but marriage and childbearing rates alone do not determine future rates of unmet need and reliance on Medicaid. How baby boomers and later generations fare will likely depend far more on continued expansion of support options for themselves and whatever configuration of informal caregivers they have.

Notes

-

People who were born between 1946 and 1964.

-

Renee Stepler, "Led by Baby Boomers, Divorce Rates Climb for America's 50+ Population," Fact Tank, Pew Research Center, March 9, 2017, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/03/09/led-by-baby-boomers-divorce-rates-climb-for-americas-50-population/.

Renee Stepler, "Number of US Adults Cohabiting with a Partner Continues to Rise, Especially among Those 50 and Older," Fact Tank, Pew Research Center, April 6, 2017, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/06/number-of-u-s-adults-cohabiting-with-a-partner-continues-to-rise-especially-among-those-50-and-older/.

-

Unmet need is measured in the NHATS as reporting at least one adverse consequence because help was not available (e.g., having to go without getting out of bed, bathing, dressing, a hot meal, or clean laundry).

-

Judith D. Kasper, memo to William Marton (Director, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Planning and Evaluation, Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy, Division of Disability and Aging Policy), HIPAA estimates using the 2011 and 2015 NHATS, 2017.

References

Brown, Kay. 2015. Older Adults: Federal Strategy Needed to Help Ensure Efficient and Effective Delivery of Home and Community-Based Services and Supports. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

Brown, Susan L., and I-Fen Lin. 2012. "The Gray Divorce Revolution: Rising Divorce among Middle-Aged and Older Adults, 1990-2010." Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(6): 731-41. doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs089.

Brown, Susan L., and Matthew R. Wright. 2017. "Marriage, Cohabitation, and Divorce in Later Life." Innovation in Aging, 1(2): 1-11. doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx015.

de Meijer, Claudine, Bram Wouterse, Johan Polder, and Mac Koopmanscap. 2013. "The Effect of Population Aging on Health Expenditure Growth: A Critical Review." European Journal of Ageing, 10(4): 353-61. doi.org/10.1007/s10433-013-0280-x.

Freedman, Vicki A., Douglas A. Wolf, and Brenda C. Spillman. 2016. "Disability-Free Life Expectancy over 30 Years: A Growing Female Disadvantage in the US Population." American Journal of Public Health, 106(6): 1079-85. doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303089.

Home Care Association of America (HCAOA) and Global Coalition on Aging. 2016. Caring for America's Seniors: The Value of Home Care. Washington, DC: HCAOA.

Houser, Ari, Wendy Fox-Grage, and Kathleen Ujvari. 2012. Across the States: Profiles of Long-Term Services and Supports. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute.

Kaye, H. Stephen. 2014. "Toward a Model Long-Term Services and Supports System: State Policy Elements. Gerontologist, 54(5): 754-61. doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu01.

Keefe, Janice, Jacques Légaré, and Yves Carrière. 2007. "Developing New Strategies to Support Future Caregivers of the Aged in Canada: Projections of Need and Their Policy Implications." Canadian Public Policy, 33(Supplemental 1): 1-16. doi.org/10.3138/Q326-4625-5753-K683.

King, Valarie, and Mindy E. Scott. 2005. "A Comparison of Cohabiting Relationships among Older and Younger Adults." Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2): 271-85. doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00115.x.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2015. The Growing Gap in Life Expectancy by Income: Implications for Federal Programs and Policy Responses. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

National Research Council. 2012. Aging and the Macroeconomy: Long-Term Implications of an Older Population. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Pickard, Linda. 2015. "A Growing Care Gap? The Supply of Unpaid Care for Older People by Their Adult Children in England to 2032." Ageing and Society, 35(1): 96-123. doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000512.

Pickard, Linda. 2008. Informal Care for Older People Provided by Their Adult Children: Projections of Supply and Demand to 2041. PSSRU Discussion Paper 2515. London: Personal Social Services Research Unit.

Redfoot, Donald L., Lynn Feinberg, and Ari Houser. 2013. The Aging of the Baby Boom and the Growing Care Gap: A Look at Future Declines in the Availability of Family Caregivers. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute.

Redfoot, Donald L., and Sheel M. Pandya. 2002. Before the Boom: Trends in Long-Term Supportive Services for Older Americans with Disabilities. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute.

About the Authors

Brenda Spillman is a senior fellow and health economist in the Urban Institute's Health Policy Center. She has more than 30 years of experience designing and conducting health and health care-related research projects. She has expertise in survey design and extensive experience with a broad range of complex national surveys, Medicare and Medicaid claims, and assessment data. She was an inaugural coinvestigator and leadership team member for NHATS, a National Institute on Aging-funded longitudinal survey of the Medicare elderly, and the companion National Study of Caregiving. She now serves on the study's steering committee.

She is a nationally recognized expert on old-age disability, long-term care use and financing, informal caregiving, and projections of service use and cost for the Medicare elderly. Ongoing work is examining demographic trends and the implications for future family and unpaid caregiver supply and demand for paid support services. Recent work has focused on chronic disease and promoting maximum health and functioning. Spillman was principal investigator for the long-term evaluation of Section 2703 Medicaid Health Homes, an initiative to improve outcomes for beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions by integrating delivery of health, behavioral, and supportive services, and for a project examining collaborations between housing and the health care system aimed at providing integrated, coordinated, whole-person care to vulnerable populations.

Before joining Urban in 1998, Spillman was a research fellow at what is now the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. She has a PhD from the Maxwell School, Syracuse University.

Melissa Favreault is a senior fellow in the Income and Benefits Policy Center at the Urban Institute, where her work focuses on the economic well-being and health status of older Americans and people with disabilities. She studies social insurance and social assistance programs and has written extensively about Medicaid, Medicare, Social Security, and Supplemental Security Income. She evaluates how well these programs serve Americans today and how various policy changes and ongoing economic and demographic trends could alter outcomes for future generations. Much of her research relies on dynamic microsimulation, distributional models that she develops to highlight how educational and economic advantages shape financial outcomes, disability trajectories, health care needs, and longevity. She has a special interest in the economic risks that people face over their lives and has studied the lifetime costs of health care, including LTSS, and of family caregivers' foregone earnings and employee benefits.

Favreault has published her research in Demography, Health Affairs, Health Services Research, and the Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences and coedited Social Security and the Family: Addressing Unmet Needs in an Underfunded System with Frank Sammartino and C. Eugene Steuerle. She served on the Social Security Advisory Board's 2011 Technical Panel on Assumptions and Methods and now serves on the board of the International Microsimulation Association.

Favreault earned her BA in political science and Russian from Amherst College and her MA and PhD in sociology from Cornell University.

Eva H. Allen is a research associate in the Health Policy Center, where she studies delivery and payment system models aimed at improving care for Medicaid beneficiaries, including people with chronic physical and mental health conditions, pregnant women, and people with substance use disorders. Her current research focuses on analyses of Medicaid work requirements, housing as a social determinant of health, and opioid use disorder and treatment.

Allen holds an MPP from George Mason University, with emphasis in social policy

Informal Caregiver Supply and Demographic Changes

This brief was prepared under contract #HHSP233201600024I between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Behavioral Health, Disability, and Aging Policy and RTI International. For additional information about this subject, you can visit the BHDAP home page at https://aspe.hhs.gov/bhdap or contact the ASPE Project Officers at HHS/ASPE/BHDAP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201; Judith.Dey@hhs.gov.

Reports Available

Family Structures and Support Strategies in the Older Population: Implications for Baby Boomers Issue Brief

- HTML version: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/family-structures-and-support-strategies-older-population-implications-baby-boomers-issue-brief

- PDF version: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/family-structures-and-support-strategies-older-population-implications-baby-boomers-issue-brief

Informal Caregiver Supply and Demographic Changes: Review of the Literature