June 2020

Printer Friendly Version in PDF Format (5 PDF pages)

ABSTRACT

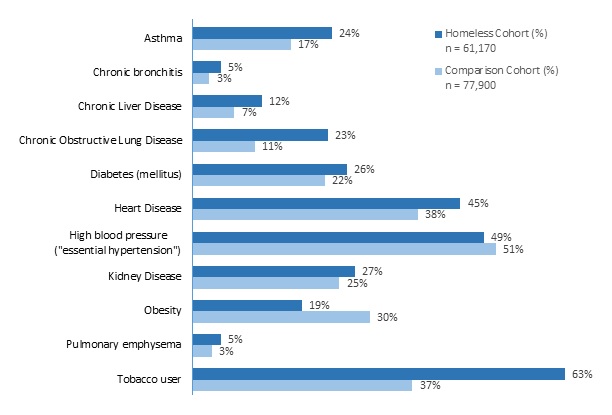

This brief uses a proprietary dataset of electronic health records to describe the prevalence rates of chronic health conditions associated with a higher risk of severe illness from COVID-19 among people with a history of homelessness. The paper found that for many of the health conditions examined, people with a history of homelessness have greater prevalence than the general population. For example, they are much more likely to have chronic respiratory conditions such as chronic obstructive lung disease (23%) or asthma (24%).

This brief was prepared through intramural research by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy. For additional information about this subject, visit the DALTCP home page at https://aspe.hhs.gov/office-disability-aging-and-long-term-care-policy-daltcp or contact the authors at HHS/ASPE/DALTCP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201, Mir.Ali@hhs.gov, Emily.Rosenoff@hhs.gov.

DISCLAIMER: The opinions and views expressed in this brief are those of the authors. They do not reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization. This brief was completed and submitted in April 2020.

|

This paper is a descriptive analysis of the prevalence rates of some chronic health conditions that are associated with a higher risk of severe illness from COVID-19 among people with a history of homelessness. It uses a proprietary dataset with electronic health records of 61,180 individuals with an ICD-10 code of homelessness between 2015 and 2019. Key findings include the following:

|

Introduction

People experiencing homelessness are at increased risk of contracting a severe illness from Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), in part because of a higher disease burden before the pandemic. The reasons that people experiencing homelessness have a higher disease burden than housed people are multi-faceted. Illness may contribute to an individual losing or re-gaining permanent housing, and the loss of a permanent home may exacerbate health conditions or lead to new diseases (for example, tuberculosis). Therefore, people experiencing homelessness often have multiple chronic and other serious health conditions (Healthcare for the Homeless, 2020).

In addition to higher rates of chronic health conditions, people currently experiencing homelessness may have additional difficulties in managing their exposure to potential infection. Following the CDC guidance of social distancing, self-quarantining, and isolating sick people from healthy people may be difficult for individuals experiencing homelessness. They may have limited access to handwashing facilities, or live in congregate living situations. Early evidence of testing at homeless shelters shows that asymptomatic transmission plays a major role in transmitting COVID-19, thus shelters may not be aware of the nature of the extent of COVID-19 among their clients until it is too late (Mosites, et al., 2020). Shelters for people experiencing homelessness can be similar to long-term care facilities--dense environments which can "amplify" the spread of the disease (Toblowsky, et al., 2020).

Not all who contract COVID-19 are treated in a hospital; the majority are encouraged to manage their symptoms at home (CDC, 2020a). Managing COVID-19 symptoms from "home" might be particularly challenging for people experiencing homelessness. They may be living in a congregate facility or in a small space without individual bedrooms (such as families in a hotel room).

This study used an all-payer electronic health record (EHR) database to estimate the prevalence of underlying medical conditions associated with higher risk of illness from COVID-19 among individuals experiencing homelessness between 2015 and 2019.

People with History of Homelessness Likely to Have Many Medical Conditions Associated with Severe Illness from COVID-19

The research about underlying health conditions associated with a more severe illness from COVID-19 is ongoing and is not yet final. The CDC guidance (CDC, 2020b), as of April 2020, is that people with the following health conditions are at higher risk:

-

Moderate to severe asthma.

-

Liver disease.

-

Chronic lung disease.

-

Diabetes.

-

Serious heart conditions.

-

Chronic kidney disease and undergoing dialysis.

-

Severe obesity (body mass index of 40 or higher).

-

People who are immunocompromised.

-

Many conditions can cause a person to be immunocompromised, including: cancer treatment; smoking; bone marrow or organ transplantation; immune deficiencies; poorly controlled HIV or AIDS; and prolonged use of corticosteroids and other immune weakening medications.

-

The present study found that individuals experiencing homelessness had increased prevalence for most medical conditions associated with severe illness from COVID-19 compared to a comparison group of people not experiencing homelessness (Figure 1) but matched on age and gender. In addition, the paper also examined several other medical conditions that public health officials have been monitoring, such as high blood pressure. Specifically, among individuals experiencing homelessness, the rate of asthma was 24% (17% in the comparison group), the rate of diabetes was 26% (22% in the comparison group), the rate of lung disease was 23% (11% in the comparison group), the rate of serious heart condition was 45% (38% in the comparison group), the rate of kidney disease was 27% (25% in the comparison group), and the rate of tobacco use was 63% (38% in the comparison group). Other health conditions such as obesity and high blood pressure were more prevalent in the comparison group.

This analysis used IBM Watson Health's Explorys all-payer EHR dataset (2015-2019). This dataset includes over 70 million unique patients from 39 United States health care systems across all 50 states. The sample for this analysis included approximately 61,180 individuals who had an ICD-10 Z-code of homelessness (59.0) by a medical service provider between the year 2015 and 2019. The comparison group included 77,900 individuals who were matched on age and gender to the population of interest but were not recorded to be experiencing homelessness. Health conditions were identified using the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine--Clinical Terms classification system or SNOMED.

| FIGURE 1. Percentage of Patients with Each Condition, by Housing Status |

|---|

|

Discussion

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals experiencing homelessness are a unique at-risk population given their lack of permanent housing, access to medical services, and other necessities. Among individuals with an ICD-10 Z-code of homelessness in this study, many have serious chronic health conditions that are associated with severe illness from COVID-19. Many of these are co-occurring disorders/morbidities. As federal, state, and local public health systems are implementing initiatives to prevent exposure to the virus, this report highlights the significant health conditions prevalent among individuals experiencing homelessness that might increase their risk of severe illness from COVID-19.

This study has several potential limitations. The Explorys database is not nationally representative, thus the rates observed in this study might not be generalizable to the entire population of individuals experiencing homelessness in the United States. Not all individuals experiencing homelessness would have their housing status documented in their EHR, so this sample may not perfectly represent the population of individuals experiencing homelessness. The health conditions identified in the study are based on lifetime prevalence, not current diagnosis. However, most of these chronic conditions are likely to be prevalent throughout the life course once an individual is diagnosed with them. A compromised immune system can be a result of a number of different conditions or treatments, as a result this study did not attempt to identify individuals who were immunocompromised. These data are from 2015-2019 and as such this analysis does not include any information on prevalence of COVID-19 symptoms, nor on prevalence of COVID-19.

REFERENCES

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC). (2020a). Caring for Someone at Home. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/if-you-are-sick/care-for-someone.html.

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC). (2020b). Information for People who are at Higher Risk for Severe Illness. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/groups-at-higher-risk.html.

Healthcare for the Homeless. (2020). COVID-19 and the HCH Community: Needed Policy Responses for a High-Risk Group. Retrieved from https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Issue-brief-COVID-19-HCH-Community.pdf.

Mosites, E., Parker, E.M., Clarke, K.E.N., Gaeta, J.M., Baggett, T.P., Imbert, E., Sankaran, M., Scarborough, A., Huster, K., Hanson, M., Gonzales, E., Rauch, J., Page, L., McMichael, T.M., Keating, R., Marx, G.E., Andrews, T., Schmit, K., Morris, S.B., Dowling, N.F., Peacock, G., & COVID-19 Homeleassness Team. (2020). Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Prevalence in Homeless Shelters--Four U.S. Cities, March 27-April 15, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6917e1.

Toblowsky, F.A., Gonzales, E., Self, J.L., Rao, C.Y., Keating, R, Marx, G.E., McMichael, T.M., Lukoff, M.D., Duchin, J.S., Huster, K., Rauch, J., McLendon, H., Hanson, M., Nichols, D., Pogosjans, S., Fagalde, M., Lenahan, J., Maier, E., Whitney, H., Sugg, N., Chu, H., Rogers, J., Mosites, E., & Kay, M. (2020). COVID-19 Outbreak Among Three Affiliated Homeless Service Sites--King County, Washington, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6917e2.