Nancy Archibald, Michelle Soper, Leah Smith, and Alexandra Kruse

Center for Health Care Strategies

Joshua Wiener

RTI International

Printer Friendly Version in PDF Format (59 PDF pages)

ABSTRACT

The 11 million individuals dually-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid are among the highest need populations in either program. However, a lack of coordination between the Medicare and Medicaid programs makes it difficult for individuals enrolled in both to navigate these fragmented systems of care and adds to the cost of both programs. Special Needs Plans (SNPs), created by Congress in 2003, are a type of Medicare Advantage (MA) plan that limits membership to people with specific diseases or characteristics. Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D SNPs), one type of SNP, enroll only individuals dual-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. As of 2013, all D SNPs must have contracts with the applicable state Medicaid program that contains a description of how the plan will provide and coordinate Medicare and Medicaid-financed care.

Although states' D SNP contracts can help to promote integrated care for dual-eligible beneficiaries, these plans face administrative and operational challenges in overcoming Medicare-Medicaid misalignment. In the last few years, several states, health plans, and the federal government have increased their efforts to overcome misalignments in Medicare and Medicaid to address some of the challenges that hindered D SNPs from more effectively coordinating care for dual-eligible beneficiaries. This issue brief highlights lessons learned from the experience of states that have used SNPs to integrate for duals and identifies a menu of administrative flexibilities under existing SNP authority to improve access to integrated services and care coordination for duals.

This report was prepared under contract #HHSP23320100021WI between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy (DALTCP) and the Research Triangle Institute. For additional information about this subject, you can visit the DALTCP home page at http://aspe.hhs.gov/office-disability-aging-and-long-term-care-policy-daltcp or contact the ASPE Project Officer, Jhamirah Howard, at HHS/ASPE/DALTCP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201; Jhamirah.Howard@hhs.gov.

DISCLAIMER: The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization. This report was completed and submitted in November 2017.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION

2. METHODS

3. OVERVIEW OF THE D-SNP LANDSCAPE

3.1. D-SNP Enrollment and Service Areas

3.2. D-SNP Contracting with States

4. POLICY OPTIONS TO IMPROVE INTEGRATION AND ALIGNMENT

4.1. Network Standards and Reviews

4.2. Care Management

4.3. Marketing

4.4. Beneficiary and Provider Notices

4.5. Data Collection and Quality Measurement

4.6. Appeals and Grievances

5. POLICY OPTIONS TO ENCOURAGE INVESTMENT IN D-SNP-BASED APPROACHES TO INTEGRATION

5.1. Encouraging Aligned Enrollment

5.2. Supporting States and Plans

5.3. Refining Payment Policies

6. POLICY OPTIONS TO IMPROVE FEDERAL-STATE COLLABORATION

7. CONCLUSION

APPENDICES

- APPENDIX A: Policy Options for HHS and States to Enhance Medicare-Medicaid Integration in D-SNPs

- APPENDIX B: Subject Matter Experts, Case Study Interviewees, and State Officials

- APPENDIX C: Additional Policy Options

LIST OF EXHIBITS

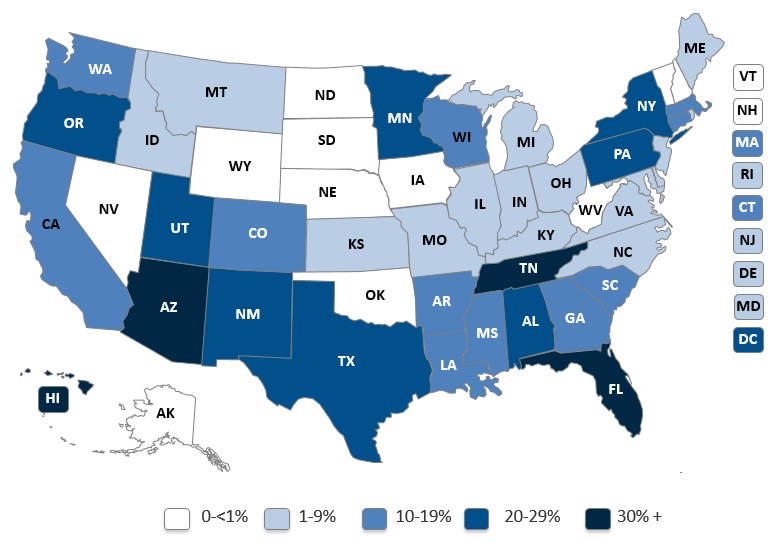

- EXHIBIT 1: Percentage of Dual Eligible Beneficiaries Enrolled in D-SNPs, 2017

- EXHIBIT 2: Tennessee's Approach to Promoting Aligned D-SNP-MLTSS Plan Enrollment

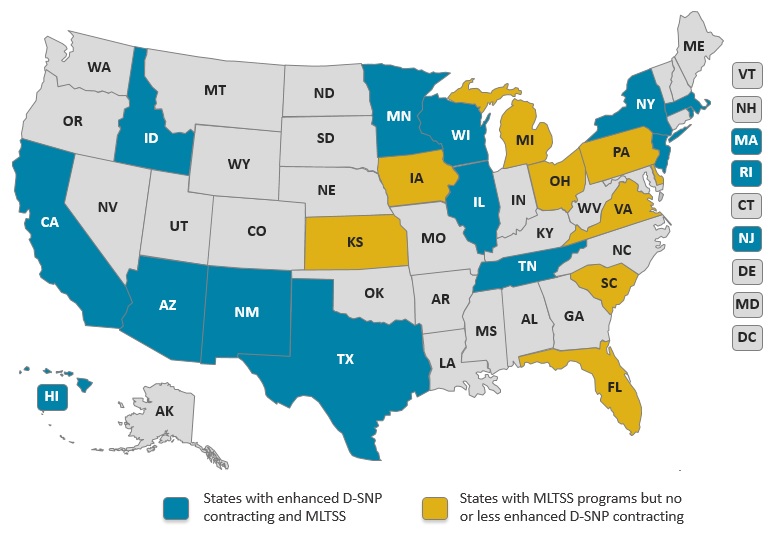

- EXHIBIT 3: States with Aligned D-SNPs and MLTSS Programs, 2017

- EXHIBIT 4: Minnesota Provides Input on D-SNP Provider Network Standards

- EXHIBIT 5: Massachusetts' Care Management Requirements Promote Continuity of Care

- EXHIBIT 6: Arizona Uses Marketing Tools to Encouraging Aligned Enrollment

- EXHIBIT 7: Massachusetts and Minnesota Use Integrated Materials to Improve Beneficiaries' Experience of Care

- EXHIBIT 8: Tennessee Requires Data Exchange to Promote Care Coordination

- EXHIBIT 9: Arizona and Tennessee Encourage Aligned Enrollment Through Seamless Conversion

- EXHIBIT 10: Criteria for FIDE SNP and Highly Integrated D-SNP Designations

- EXHIBIT 11: New Jersey Uses FIDE SNPs to Provide Integrated Care

ACRONYMS

The following acronyms are mentioned in this report and/or appendices.

| AHCCCS | Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System |

|---|---|

| CFR | Code of Federal Regulations |

| CHIP | Children's Health Insurance Program |

| CMS | HHS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

| D-SNP | Dual Eligible Special Needs Plan |

| FIDE SNP | Fully Integrated Dual Eligible Special Needs Plan |

| GAO | U.S. Government Accountability Office |

| HHS | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

| HPMS | Health Plan Management System |

| LTSS | Long-Term Services and Supports |

| MA | Medicare Advantage |

| MACPAC | Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission |

| MedPAC | Medicare Payment Advisory Commission |

| MIPPA | Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act |

| MLTSS | Managed Long-Term Services and Supports |

| MMCO | CMS Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office |

| NAMD | National Association of Medicaid Directors |

| PACE | Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly |

| SCO | Senior Care Options |

| SNP | Special Needs Plan |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Background and Objectives. The 11 million individuals dual eligible for Medicare and Medicaid are among the highest need populations in either program. However, a lack of coordination between the Medicare and Medicaid programs makes it difficult for individuals enrolled in both to navigate these fragmented systems of care and adds to the cost of both programs.

Special Needs Plans (SNPs), created by Congress in 2003, are a type of Medicare Advantage (MA) plan that limit membership to people with specific diseases or characteristics. Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs), one type of SNP, enroll only individuals dual eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. DSNPs seek to provide enrollees with a coordinated Medicare and Medicaid benefit package. These plans first began operation in 2006, and their enrollment has increased steadily, but there is opportunity for further growth. As of 2013, all DSNPs must have contracts with the applicable state Medicaid program that contains a description of how the plan will provide and coordinate Medicare and Medicaid-financed care.

States can use their DSNP contracts to encourage or, in some cases require, these plans to integrate certain Medicare and Medicaid programmatic elements by blending the programs' disparate care management and administrative processes and policies into one unified delivery system. States can also work with their DSNPs to improve the alignment of Medicare and Medicaid so that the programs work more seamlessly when administrative processes cannot be combined.

Although states' DSNP contracts can help to promote integrated care for dual eligible beneficiaries, these plans continue to face administrative and operational challenges in overcoming Medicare-Medicaid misalignment. Recent initiatives within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have made progress in addressing misalignment, but challenges remain. Despite these challenges, DSNPs may still be the most readily available and scalable platform to integrate care for dual eligible beneficiaries. The purpose of this report is to identify policy options for consideration by policymakers for enhancing DSNPs as a platform to integrate care for this population. These policy options are not recommendations and comprehensive pros and cons are not presented.

Methods. This study gathered information from a variety of sources, including: (1) an environmental scan of peer-reviewed and "gray" literature and other public documents; (2) telephone interviews with five subject matter experts; (3) telephone case studies of five states (Arizona, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Tennessee) that are advancing DSNP-based integration models; and (4) a meeting in Washington, DC, of officials from Arizona, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin, all states which are building or refining integration models based on DSNPs.

This information was used to develop a list of: (a) federal policy options, including administrative flexibilities, that could be adopted by HHS; and (b) state policy options that could be used to improve integration and coordination of care under existing authority.

Findings. Findings drawn from the study include the following:

-

Delivery System Reform for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries: Given dual eligible beneficiaries' complex clinical, functional, and social profiles and very low incomes, state officials report that this population needs a different level of services and supports than the general Medicare beneficiary population. Ideally, states would like DSNP-based integrated care programs to be treated as a new delivery system, distinct from MA, with its own policies and procedures specially tailored to the needs of dual eligible individuals. Short of creating a new delivery system, states would like CMS to consider how the guidance provided for the administration and oversight of MA plans can better serve the needs of DSNPs.

-

Medicaid Parity with Medicare: In many instances, state officials believe that Medicaid program goals and requirements are placed at a lower priority than those of the Medicare program when federal policies and programs related to integrated care are being developed. Although states appreciate the opportunity to comment on rules and other guidance written by CMS related to dual eligible populations--such as the recently created Integrated Denial Notice and Summary of Benefits notice--they would like to more actively participate with CMS on policies that directly affect their dual eligible beneficiaries.

-

Priority Issues for Administrative Alignment: State officials identified two priority issues for improving Medicare and Medicaid administrative alignment: care management and network standards. They believe that care management of Medicare and Medicaid services is the cornerstone of integrated care, and that challenges in coordinating MA's DSNP care management requirements--embodied in the Model of Care developed by each plan--with the care management requirements of their managed long-term services and supports programs create a significant barrier to alignment. For example, states want to require DSNPs' Models of Care to include descriptions of how the plans will conduct assessments of enrollees' long-term services and supports (LTSS) needs and develop integrated Medicare-Medicaid care plans, but CMS auditors have questioned the appropriateness of including such elements in the Model of Care.

Currently, CMS's network adequacy standards treat all MA plans similarly regardless of the population enrolled. States and plans both emphasized that MA network adequacy standards do not account for: (1) specific state geographic characteristics that can affect provider availability; and (2) the ability of DSNPs to expand access to care by combining MA networks with state Medicaid service offerings, such as non-emergency transportation benefits, which may enhance access. Although DSNPs may submit network exception requests to CMS to address geographic barriers, states believe that current MA network adequacy standards limit health plan participation and beneficiary enrollment. Although all stakeholders agree that dual eligible are a high-risk population needing extensive services and better access than offered by typical MA plans, some observers are concerned that modifying the network adequacy standards to give more exceptions to D-SNPs could result in approval of plans with insufficient provider networks. They would prefer that any problems with the MA standards, such as inadequate recognition of geography, be resolved for all beneficiaries.

-

Priority Issue for Increasing DSNP Enrollment: Seamless Conversion. Although CMS prohibits mandatory enrollment in MA plans, it had, under narrow circumstances, allowed approved plans to "seamlessly convert" (i.e., passively enroll) Medicare individuals enrolled in a plan's non-Medicare products (e.g., commercial or Medicaid plans) into its MA plans (including DSNPs) as the beneficiary becomes newly eligible for Medicare (i.e., turning age 65 or completing the 2-year Social Security Disability Insurance waiting period). Beneficiaries enrolled in this manner must be given written notice at least 60 days prior to the effective date of their Medicare coverage and may opt out at any time before coverage begins.

In October 2016, following inquiries about how plans are using this mechanism and related beneficiary protections, CMS placed a temporary moratorium on new plan approvals for seamless conversion while it reviews current policies, although already-approved plans may continue. State officials believe this moratorium hinders integrated care; they see seamless conversion not just as a mechanism to increase DSNP enrollment but as an opportunity to improve care management because one entity becomes responsible for coordination of both Medicare and Medicaid services. The states asked for DSNPs to be excluded from the moratorium because enrollment in aligned plans that otherwise meet CMS quality and other performance standards affords beneficiaries more protections by providing better care management and reduced fragmentation of care. However, some stakeholders may view seamless conversion, along with other policies that passively enroll beneficiaries into a health plan, as an infringement on beneficiary protections, even if the individual has an opportunity to refuse enrollment beforehand and opt out any time thereafter.

-

State Commitment to Integrated Care: State officials strongly support integrated care for their dual eligible populations; however, their ability to implement these programs is constrained by limited resources. Competing priorities often mean that important tasks such as analysis of utilization from plan encounter data or stakeholder engagement work have lower priority than other Medicaid delivery system reform efforts. They requested more financial and other support for their integration efforts.

-

Legislative, Regulatory, or Systems Change Will Be Needed: CMS staff have been working within existing authorities to remove Medicare-Medicaid misalignments. However, many potential solutions (e.g., integrated appeals processes, changes in the notification process for benefit denials) cannot be made without legislative, regulatory, or systems changes.

-

Role of CMS Technical Assistance: States requested that CMS provide more technical assistance tools detailing steps that states could take to strengthen their integration efforts via DSNP-based programs. They suggested that these materials be tailored to states at varying stages of design and implementation of integrated care programs.

The policy options presented in this report represent findings from the literature, discussions with subject matter experts, and a roundtable of state health officials. The policy options presented are NOT recommendations or official statements of HHS policy positions.

Policy Options. We identified specific policy options that could be adopted by HHS or states. Appendix A contains a complete list of all the policy options identified. Policy options that states considered particularly important include the following:

-

HHS could work with states to develop DSNP-specific network adequacy standards.

-

HHS could promote greater integration of the Medicare Model of Care requirements with state Medicaid care management requirements.

-

States could modify Medicaid managed care marketing criteria to align with MA practices.

-

States could conduct more beneficiary education and outreach activities.

-

HHS could develop more integrated beneficiary and provider materials to be used by DSNPs.

-

States could provide DSNPs with data on beneficiaries' service utilization history.

-

HHS could change the notification process around benefit denials for beneficiaries enrolled in aligned plans.

-

HHS could lift the temporary moratorium on new approvals for seamless conversion submitted by DSNPs.

-

States could align their Medicaid annual open enrollment period with the MA open enrollment period.

-

HHS could provide more guidance around the Fully Integrated Dual Eligible Special Needs Plan (FIDE SNP) and highly integrated DSNP designations.

-

HHS could explore ways to make the frailty payment adjuster for FIDE SNPs available at the beneficiary level rather than the plan level.

-

HHS could offer states with integrated DSNP programs the opportunity for joint CMS/state oversight calls.

Considerations. The policy options listed in this report may help HHS and states advance Medicare-Medicaid integration for dual eligible beneficiaries through DSNPs. Nonetheless, there are several overarching issues regarding DSNPs that should be considered in assessing these policy options. To date, there has been little comparative outcomes data showing that DSNPs deliver better care for dual eligible beneficiaries than either regular MA plans or the uncoordinated Medicare and Medicaid fee-for-service delivery systems. Both states and health plans will need to demonstrate the value of DSNP-based integrated care programs to both beneficiaries and providers to secure their participation. In addition, DSNPs may not be able to or interested in serving rural areas because of the lack of enrollees or providers. Finally, the lack of access to Medicare savings resulting from the improved care coordination provided by DSNP or other integrated care programs may limit state interest in investing in these programs.

Conclusion. DSNP-based integrated care programs have the potential to provide the full array of Medicare and Medicaid services under one entity, improve care management, and address some administrative barriers faced by dual eligible beneficiaries. These advantages have allowed DSNPs to grow in both numbers and enrollment. States, plans, and the Federal Government have worked to overcome Medicare-Medicaid misalignments that have impeded the ability of DSNPs to become a fully integrated vehicle for serving dual eligible beneficiaries. Many states see DSNPs as having the potential to improve the care of dual eligible individuals. States remain eager to work with health plans and federal partners to make DSNP-based integrated care a more important option for this vulnerable population.

1. INTRODUCTION

The 11 million people dual eligible for Medicare and Medicaid are among the highest cost enrollees in either program, and many have physical health, behavioral health, and long-term services and supports (LTSS) needs (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office [CMS MMCO], 2016a; Medicare Payment Advisory Commission and Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission [MedPAC-MACPAC], 2017; CMS, 2014a). However, the lack of coordination between Medicare and Medicaid has made it difficult for dual eligible individuals to receive needed care and has also increased program costs.

Over time, a variety of mechanisms have been created to foster Medicare-Medicaid integration--the blending of the programs' disparate care management and administrative processes and policies into unified program elements. Other efforts have tried to improve the alignment of Medicare and Medicaid to make processes and policies work more seamlessly in areas where they cannot be combined. A few programs attempt to create an integrated system of care at the program and delivery systems level. For example, the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) completely integrates Medicare and Medicaid benefits and financing in a geriatric care model built on an adult day health platform (National PACE Association, 2016). More recently, the Financial Alignment Initiative demonstrations, in 12 states across the country, are testing capitated and managed fee-for-service approaches to providing integrated care (Chepaitis et al., 2015). However, these two approaches have their limitations. Enrollment in PACE has grown slowly, reflecting some of the limitations of the model (Gross et al., 2004).[1] In addition, not all states were able to take part in the Financial Alignment Initiative demonstrations, and it is uncertain whether this model will become a permanent part of the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

Other more-scalable and permanent options are needed to integrate care for dual eligible beneficiaries. Because of their presence in most states, Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs), a type of Medicare Advantage (MA) managed care plan, are a readily available platform for increasing the number of people in integrated care and better aligning Medicare and Medicaid policies. DSNPs enroll only individuals dual eligible for Medicare and Medicaid; are required to have an approved care management model describing how each plan will meet the needs of its enrollees; and arrange for or provide enrollees with a coordinated Medicare and Medicaid benefit package (CMS, 2016b).[2]

When they were first authorized by Congress in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, DSNPs were not required to have any formal relationship with state Medicaid agencies. However, to facilitate coordination of Medicare and Medicaid services, the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (MIPPA) of 2008--as amended by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act--required all DSNPs to have contracts with the states in which they operate (CMS, 2016b). Now, at a minimum, DSNPs must either: (1) include Medicaid benefits in their capitated benefit package; or (2) arrange for Medicaid benefits to be provided in some other way such as through a companion Medicaid managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) program, a Medicaid managed care plan, or through Medicaid fee-for-service providers, depending on the state. DSNPs have the potential to deliver a coordinated Medicare and Medicaid benefit package that offers more integrated care than regular MA plans or traditional Medicare fee-for-service.

As an integration platform, DSNPs differ in several ways from the Medicare-Medicaid Plans used in the Financial Alignment Initiative demonstrations. First, the special authority of the demonstrations offers Medicare-Medicaid Plans the opportunity to fully integrate administrative processes including marketing, beneficiary notices, grievances and appeals, and quality measurement. DSNPs do not have the same opportunity to overcome misalignments in Medicare and Medicaid administrative processes. Medicare-Medicaid Plans receive capitated payments from Medicare and Medicaid. DSNPs receive capitated payments from Medicare, but only a small subset of these plans that provide some level of Medicaid benefits receive Medicaid capitation, which creates a financial barrier to integration. Finally, the degree of Medicare-Medicaid integration attained through DSNPs is dictated by the goals and priorities of the states in which they operate.

Through several initiatives over the last few years, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has made progress in addressing many of the misalignments between Medicare and Medicaid (CMS, 2011; CMS MMCO, 2016a). However, many misalignments remain and must be overcome before the DSNP platform can be used more widely in a fully integrated manner. The purpose of this report is to identify policy options that would advance the use of DSNPs as an integration platform by: (1) resolving misalignments in Medicare and Medicaid processes and procedures; (2) encouraging both states and health plans to invest in DSNP-based integration models; and (3) facilitating collaboration between states and CMS. The policy options presented in this report are NOT recommendations or official statements of HHS policy positions.

2. METHODS

We gathered information from a variety of sources on the use of DSNPs as an integration platform:

-

Environmental scan. An environmental scan examined both peer-reviewed and "gray" literature and other public documents related to: (1) DSNP structures and operations; (2) state-level progress with and challenges of using DSNPs to serve dual eligible populations; and (3) trends in DSNP markets. A major purpose of the environmental scan was to generate topics for discussion with subject matter experts, case study participants, and state officials.

-

Subject matter expert interviews. For a detailed, up-to-date understanding of issues and options related to the use of DSNPs as a platform for Medicare-Medicaid integration, the project team conducted five telephone interviews with subject matter experts. (See Appendix B for a list of experts interviewed.) The hour-long interviews covered a wide range of topics, with questions targeted to the interviewees' areas of expertise.

-

State case studies. Building on the information gathered from the environmental scan and interviews with subject matter experts, we conducted case studies of five states (Arizona, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Tennessee), which are all actively using DSNP-based integration models. In each state, the project team spoke with state staff responsible for program design and ongoing contract management and representatives from DSNPs operating in that state. (See Appendix B for a list of state agencies and DSNPs interviewed.) The objectives of the case studies were to: (1) identify states' accomplishments using the DSNP platform to achieve Medicare-Medicaid integration and alignment; (2) understand how they made those accomplishments; and (3) determine what policy changes would help them to further their innovations. Information gleaned from the case studies is included in exhibits throughout this report.

-

Meeting of state officials. Finally, we convened a meeting of officials from ten states (Arizona, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin), all of which are building or refining integration models based on DSNPs. (See Appendix B for a list of state officials attending the meeting.) The meeting was held at the Hubert H. Humphrey Building in Washington, D.C., on October 24, 2016. The goal of the meeting was to review a series of policy options that emerged from the literature review, interviews with subject matter experts, and the state case studies. Through facilitated discussion, the state representatives assessed the proposed policy options and provided insights based on their own experiences.

The information gathered from these four activities was used to develop:

-

Federal policy options, including administrative flexibilities, that are available to HHS.

-

State options under existing authority that could improve integration and coordination of care.

This report presents these options for consideration by policymakers and describes how they could help states and health plans to make DSNPs a more robust platform to integrate care for dual eligible individuals.

The body of the report lists the top 12 policy options which could have the greatest impact on encouraging: (1) growth in DSNP enrollment; (2) expansion of DSNPs into more service areas; and (3) strengthened contracts between states and DSNPs to provide more integrated and aligned care. The options are not recommendations. Appendix C lists additional policy options identified through this project that could be considered by states and HHS to improve integration or alignment in the DSNP platform.

3. OVERVIEW OF THE DSNP LANDSCAPE

The DSNP landscape can be viewed from a variety of perspectives, including the number of dual eligible beneficiaries these plans enroll, their service areas, and the degree of Medicare-Medicaid integration required in the contracts that they have with states.

3.1. DSNP Enrollment and Service Areas

Since DSNPs first began operation in 2006, the number of enrollees has grown steadily (Verdier et al., 2016). In 2006, there were 256 DSNPs with 491,877 enrollees; as of February 2017, there were 378 DSNPs with 1,922,183 enrollees--about 20 percent of the total dual eligible population (CMS, 2017a; Milligan & Woodcock, 2008). Although 41 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico have DSNPs, enrollment is highly concentrated: 63 percent of enrollment is in ten states (Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas) (Verdier et al., 2016).[3] Exhibit 1 shows the percentage of the dual eligible population enrolled in DSNPs in each state.

| EXHIBIT 1. Percentage of Dual Eligible Beneficiaries Enrolled in D-SNPs, 2017 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. SNP comprehensive report. (2017a). |

The total number of DSNPs has been stable from year to year (Verdier et al., 2016). For 2017, there are 29 new DSNPs and 15 DSNPs departing their markets (Integrated Care Resource Center, 2016a). Kansas, Nebraska, and Rhode Island did not have any DSNPs in 2016, but one plan is available in each state in 2017. Idaho's one DSNP experienced a significant service area reduction between 2016 and 2017 that has decreased its enrollment by 8 percent (Integrated Care Resource Center, 2016a).

The growth of enrollment in DSNP-based integration models is influenced by both state and health plan interest in this integration platform. The nine states that have no DSNPs in 2017 (Alaska, Iowa, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming) all have MA organizations that could potentially choose to offer DSNPs. In still other states, there are a significant number of counties or other service areas with no DSNPs--markets into which these plans could potentially expand.

3.2. DSNP Contracting with States

To improve the integration of Medicare and Medicaid benefits, MIPPA--as amended by the Affordable Care Act--required all DSNPs to have contracts with the states in which they operate, effective January 1, 2013 (CMS, 2016b). These State Medicaid Agency Contracts, also called "MIPPA contracts," require DSNPs to provide Medicaid benefits, or arrange for benefits to be provided, and serve and coordinate care for dual eligible enrollees (Verdier et al., 2016). At a minimum, DSNP MIPPA contracts with states must document eight elements (42 CFR §422.107):

-

The DSNP's responsibility, including financial obligations, to provide or arrange for Medicaid benefits.

-

The categories of eligibility for dual eligible beneficiaries to be enrolled under the Special Needs Plan (SNP) (full Medicaid, Qualified Medicare Beneficiaries, Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiaries, etc.).

-

The Medicaid benefits covered under the SNP.

-

The cost-sharing protections covered under the SNP.

-

The process by which the state will identify and share with the SNP information on providers contacted with the state Medicaid agency.

-

The process by which the SNP will receive real-time information to verify enrollees' eligibility for both Medicare and Medicaid.

-

The service area covered by the SNP.

-

The contract period for the SNP.

Although MIPPA's minimum requirements oblige DSNPs to describe how they will provide or arrange for Medicaid services for enrollees, contracts meeting only the minimum requirements do not require integration or alignment of Medicare and Medicaid administrative processes (e.g., enrollment processes, marketing guidelines, network adequacy review) (MedPAC, 2013). However, states can include language in their MIPPA contracts with DSNPs to require or at least encourage administrative alignment and benefit integration (Verdier et al., 2016). In addition, states have several program design options that can increase the degree of Medicare-Medicaid integration and alignment in their DSNP-based programs, including from least to most aligned (Archibald & Kruse, 2015):

-

Include Medicare Cost-Sharing, Medicaid Wraparound Services, or Both: States can require DSNPs to pay enrollees' Medicare premiums and cost-sharing out of their capitation payments (state Medicaid agencies would otherwise pay for premiums or cost-sharing directly), which can help to coordinate claims processing, reduce administrative burden on providers, and decrease instances of balance billing of enrollees. States may also contract with DSNPs to provide Medicaid acute care services not covered or only partially covered by Medicare (e.g., vision, dental, hearing, durable medical equipment, transportation, and care coordination).

-

Include Medicaid LTSS or Behavioral Health Services: States can require DSNPs to provide or arrange for Medicaid LTSS or behavioral health services. States that have established a high-degree of benefit integration under these arrangements are in a better position to pursue administrative alignment of Medicare and Medicaid processes and materials (e.g., marketing materials, beneficiary and provider notices).

-

Align DSNPs and MLTSS Programs: DSNP contracts can be used to align a state's Medicaid managed care plans, including MLTSS plans, with DSNPs operating in the state by requiring the entities offering Medicaid plans to also offer companion DSNPs covering the same geographic area, or conversely, by requiring the entities offering DSNPs to offer MLTSS plans. DSNPs may achieve high levels of administrative, financial, and clinical alignment when they are paired with companion Medicaid MLTSS plans for individuals who enroll in the same plan for both Medicare and Medicaid services (e.g., creating a single enrollment process and form, care management model, benefits determination process) (Integrated Care Resource Center, 2014b). Twenty-two states currently have MLTSS programs for some or all of their populations, two more states will begin implementation in 2017, and several more programs are in the design stage (Center for Health Care Strategies, forthcoming). Consequently, more states may have the opportunity to align DSNPs and MLTSS programs. Exhibit 2 describes Tennessee's approach to promoting aligned DSNP-MLTSS plan enrollment.

-

Require DSNPs to Become Fully Integrated Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (FIDE SNPs): FIDE SNPs are a special type of DSNP that must coordinate and be at risk for coverage of both Medicare and Medicaid services, including LTSS, in return for a capitated payment. FIDE SNPS must also have procedures in place for administrative alignment of Medicare and Medicaid processes and materials. States can require DSNPs to request designation from CMS as a FIDE SNP by submitting their MIPPA contracts for CMS review and approval. FIDE SNPs may be eligible to receive additional Medicare payments depending on the overall frailty level of their enrollees (CMS, 2016b). FIDE SNPs are the most integrated delivery model outside of the PACE and the Financial Alignment Initiative demonstrations (Verdier, 2015).

| EXHIBIT 2. Tennessee's Approach to Promoting Aligned D-SNP-MLTSS Plan Enrollment |

|---|

|

Tennessee's Medicaid agency--the Bureau of TennCare--seeks to improve care coordination for dual eligible beneficiaries by having a single entity be responsible for providing both Medicare and Medicaid services. Several DSNPs were already operating in Tennessee when the state launched its MLTSS program, TennCare CHOICES in LTSS, in 2010. In late 2013, as part of a statewide procurement, the state required all its Medicaid managed care contractors to offer both a TennCare CHOICES plan and a DSNP. These new contracts were effective January 1, 2015. This requirement created an aligned platform that allows one organization to coordinate an enrollee's Medicare and Medicaid services. Currently, the state has six DSNPs, three of which operate companion MLTSS plans. |

States' MIPPA contracts with DSNPs are often not publicly available, so the extent to which states employ these different contracting options is not well documented.[4] A recent analysis from the Integrated Care Resource Center found that 13 states go beyond MIPPA's minimum requirements (Verdier et al., 2016). An increasing number of states are developing Medicaid MLTSS programs, which is a factor that may encourage more states to use their MIPPA contracting options to strengthen Medicare-Medicaid integration. Exhibit 3 shows states that have aligned DSNPs with MLTSS programs using program design strategies and MIPPA contract language and states with MLTSS programs that have the potential to create aligned DSNP/MLTSS programs.[5]

| EXHIBIT 3. States with Aligned D-SNPs and MLTSS Programs, 2017 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Verdier et al. (2016) and Center for Health Care Strategies (forthcoming). |

4. POLICY OPTIONS TO IMPROVE INTEGRATION AND ALIGNMENT

The policy options presented in this report represent findings from the literature, discussions with subject matter experts, and a roundtable of state health officials. The policy options presented are NOT recommendations or official statements of HHS policy positions.

Misalignment in the administrative functions of the Medicare and Medicaid programs creates significant burdens for states and health plans trying to provide integrated care to dual eligible beneficiaries. For example, differing processes and timelines for appeals can create confusion for beneficiaries who must keep track of whether Medicare or Medicaid covers the specific services they receive even though they may be enrolled in a DSNP responsible for providing these services.

In this section, we discuss areas where changes in federal and state policies could improve Medicare and Medicaid integration and alignment within DSNP-based integrated care programs: (a) network standards and reviews; (b) care management; (c) marketing; (d) beneficiary and provider notices; (e) data collection and quality measurement; and (f) grievances and appeals. For each area, we present policy options that, if pursued, may have the greatest impact in enhancing the degree of Medicare-Medicaid integration attainable by DSNPs. This section also briefly discusses other administrative functions (appeals and grievances and benefit integration) where there are opportunities to improve Medicare and Medicaid integration and alignment via DSNPs. Appendix C contains additional policy options that may be more difficult to pursue or may be of lower priority.

4.1. Network Standards and Reviews

DSNPs must have provider networks that ensure access to the full range of covered services. However, differing Medicare and Medicaid standards and review processes can pose a challenge to fulfilling this requirement:

-

CMS specifies the required number of MA providers and facility types for every county in every state and time and distance requirements for how long and how far beneficiaries should be made to travel to access providers and facilities.[6] These requirements are based on the population size and demographics of the general MA population, as opposed to Medicaid provider network adequacy standards, which vary by state and are outlined in state Medicaid agency health plan contracts that must conform to federal Medicaid standards (42 CFR §438.206(a); 42 CFR §438.207(b); Integrated Care Resource Center, 2016b).[7]

-

CMS evaluates network adequacy at the contract level--which for any MA organization may include both many regular MA plans and D-SNPs--rather than at plan-level, so an individual DSNP's network may not necessarily be aligned with the needs of that specific enrolled plan population (CMS, 2017b).

-

MA network adequacy reviews do not consider the availability of Medicaid's non-emergency medical transportation benefit to dual eligible beneficiaries, which may improve access to services.

States and health plans cited instances where less detailed attention to geography in the MA standards led to DSNP networks being rejected. One state provided an example in which DSNPs were told by CMS to include in their networks providers located across a lake that, while perhaps a mile away straight across the lake, would require a day's drive. This circumstance was accounted for in the state's Medicaid provider network requirements, but not in the MA standards.

Network adequacy is central to the development of DSNP-based integrated care programs providing both Medicare and Medicaid services. In addition, MA organizations can drop counties from their service areas if provider networks in those counties do not meet the standards, but this poses a problem for states with MLTSS programs that require their Medicaid contractors to offer a DSNP.[8] If the MA organization cannot offer a DSNP in a service area, then its companion Medicaid plan could lose its contract for that same area, causing the state to miss an opportunity to encourage enrollment in an aligned Medicare and Medicaid program.

The following policy option could address many of these issues:

-

Policy Option 1: HHS could work with states to develop DSNP-specific network adequacy standards and processes that:

-

Provide greater flexibility in the application of Medicare time and distance standards to better reflect Medicaid standards and to account for unique geographies while ensuring that any tailored requirements meet the specific needs of the enrolled population.

-

Consider the availability of Medicaid's non-emergency medical transportation benefit when assessing network adequacy for individuals who would depend on this assistance.

-

Give state Medicaid officials the option to participate in CMS reviews of integrated DSNP service area expansions and exception requests.

-

Review provider networks at the DSNP level rather than the contract level when the MA contract includes non-DSNP products.

Rationale: During our case studies and in-person meeting, state officials said that revising DSNP network adequacy standards is one of their highest priority issues. States argued that if they were included in the DSNP network review process, it could provide CMS with a better understanding of specific geographies and other unique state characteristics and could help CMS to more effectively assess network adequacy for DSNPs. CMS has allowed Minnesota to exercise this option through its demonstration program, and the state reported that this is a valuable process. Exhibit 4 illustrates how Minnesota has provided input to CMS on DSNP provider network standards.

In addition, states would like an opportunity to explain how dual eligible beneficiaries' access to Medicaid's non-emergency medical transportation benefit can expand access to services by transporting them to providers outside of their immediate area, supporting individuals who do not own cars, or helping them get to providers not accessible by public transportation. HHS estimated that states spent $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2012 on non-emergency medical transportation (U.S. Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2014a). However, this same study noted that, in many states, access to and the quality of transportation services requires improvement.

Lastly, reviewing provider networks at the plan level would allow for greater alignment of MA and Medicaid network adequacy reviews that is not possible when MA network adequacy is reviewed at the contract level. State officials suggested that a plan-level review would more clearly highlight potential network deficiencies in the types of providers most critical in serving dual eligible populations. CMS now can offer this plan-level review using new network mapping functionalities in the Health Plan Management System (HPMS).[9]

CMS is exploring options to revise MA provider standards. In its recently released Advance Notice of Methodological Changes for Calendar Year 2018 for Medicare Advantage Capitation Rates and 2018 Call Letter, CMS asked for comments on whether it should establish different provider network standards specifically for DSNPs and whether or how such criteria could better ensure DSNPs meet the health care needs of the populations they enroll (CMS, 2017c).

It is important to note that tailoring network standards for DSNPs to account for certain circumstances must reflect the clinical and service needs of dual eligible beneficiaries who tend to have a greater number of and more complex, chronic conditions and functional limitations. There are instances in which Medicare standards offer greater beneficiary access. For example, one state noted that Medicare standards provided greater access to behavioral health specialists compared to its state requirements. Both states and plans agreed that CMS should consider the specific needs of DSNP enrollees (e.g., higher rates of serious mental illness, dementia, heart disease) when establishing new requirements. Some stakeholders are concerned that modifying the network adequacy standards to give more exceptions to D-SNPs could result in approval of plans with insufficient provider networks. They would prefer that any problems with the MA standards, such as inadequate recognition of geography, be resolved for all beneficiaries.

-

| EXHIBIT 4. Minnesota Provides Input on D-SNP Provider Network Standards |

|---|

|

The Minnesota Demonstration to Align Administrative Functions for Improvements in Beneficiary Experience is testing new provider network standards and review methods to better reflect where dual eligible individuals live and what services they use. Also, the state provides CMS with input on: (1) issues to consider while assessing plans' provider networks; and (2) plans' network exception requests. CMS staff reported that Minnesota provided very helpful information that allowed for the development of better, more consumer-friendly network standards. Minnesota's FIDE SNPs reported that this network adequacy review process more accurately reflected the needs of their enrollees. State officials would like to extend this process to the review of service area expansion and exception requests, where they believe that state Medicaid directors should be consulted more routinely. |

4.2. Care Management

Care management tasks performed by DSNPs include: (1) conducting assessments of new enrollees; (2) developing care plans; (3) arranging visits to care providers; (4) ensuring medication reconciliation; (5) connecting individuals to social and community supports; and (6) facilitating communication among an interdisciplinary care team. Effective care management is needed to meet the multidisciplinary needs of dual eligible individuals (Ensslin & Barth, 2015). MA and state Medicaid programs have care management requirements for DSNPs and MLTSS plans. CMS has established a framework for the development and approval of a Model of Care for all SNPs, including DSNPs, in which plans describe the quality, care management, and care coordination processes that will be used to address the unique needs of their enrollees (CMS, 2014b).[10] The National Committee for Quality Assurance reviews and scores the Model of Care submissions. For MLTSS programs, states develop care management requirements for person-centered needs assessment, service planning, and service coordination that are consistent with CMS guidance and regulations and that are implemented through their contracts with Medicaid managed care organizations (CMS, 2013, 2014c).

Providing care management under separate Medicare and Medicaid systems creates significant administrative burdens. MA and state Medicaid managed care contracts have different requirements for needs assessments, care planning, and monitoring. Integrated DSNPs must assure each program that its requirements are met while offering a unified, integrated product to enrollees (Burwell et al., 2010). For example, DSNPs participating in Minnesota's Senior Health Options program must conduct assessments of enrollees using both the plan's MA Health Risk Assessment tool and the MnCHOICES assessment tool for the state's MLTSS programs. The areas covered by the assessments overlap in several areas, including clinical history, functional status, medication use, and cognitive status (Ingram et al., 2013). In a truly integrated program, these separate assessments might be combined into one, thus reducing the burden on both dual eligible enrollees and the plans.

The following policy option could address some of these misalignments:

-

Policy Option 2: HHS could promote greater integration of the MA Model of Care requirements with state care management requirements for DSNP-based programs by allowing states to include Medicaid care management requirements in the DSNP Model of Care. The development of a formal process for inclusion of Medicaid requirements would allow states and DSNPs to create a comprehensive Model of Care for D-SNP-based integrated programs. In addition to formalizing a state process, HHS and states could work together to consider how to better understand varying care management activities for dual eligible beneficiaries enrolled in DSNPs by developing audit guidance for DSNPs that accounts for state-specific requirements that have been added to the Model of Care. Finally, CMS could review the impact of its requirement for contract-level Model of Care submissions on states' and health plans' alignment efforts.

Rationale: State officials agreed that care management was one of their highest priorities among the Medicare-Medicaid integration issues. They said that improved care coordination is central to the potential value of DSNPs and aligned DSNP/MLTSS programs. State officials believed it is imperative that they can add state Medicaid-specific elements to the DSNP Model of Care to make these programs work as intended. For example, states want to require DSNPs' Models of Care to include descriptions of how the plans will conduct assessments of enrollees' LTSS needs and develop integrated Medicare-Medicaid care plans. (Exhibit 5 describes how Massachusetts requires plans to inventory enrollees' LTSS needs.) Although SNP Model of Care criteria do broadly allow DSNPs to insert state Medicaid-specific elements, the states and plans interviewed for this project reported that some CMS auditors, at least in early auditing cycles, have questioned the appropriateness of including such elements in the Model of Care.

Some plans have asked CMS to be allowed to submit an integrated Medicare-Medicaid Model of Care so that the state and CMS could review it concurrently. Minnesota's demonstration program is testing concurrent CMS and state review of plans' Models of Care. Although state Medicaid officials could see the Model of Care submissions in their entirety, including both Medicare and Medicaid elements, they were only permitted to comment on the Medicaid elements the plans had inserted. Minnesota state Medicaid staff believe that, because the Model of Care is so central to providing truly integrated care, they should be able to comment on all elements, including the Medicare-only requirements. CMS staff acknowledged that there may be value in concurrent Model of Care review if the integrity of the National Committee for Quality Assurance review process is not compromised. They also foresee challenges in auditing state-specific Model of Care elements across 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. States expressed a desire to establish a closer partnership with CMS to strengthen care management within integrated care programs.

Effective in contract year 2017, MA organizations operating multiple DSNPs under a single MA contract--which may span several states--must have a single Model of Care applicable to all the DSNPs under that contract (Integrated Care Resource Center, 2016b). Although DSNPs can tailor subsections of their Model of Care to an individual state's population or program as needed (CMS, 2015a), state officials strongly felt that having a single Model of Care across an entire contract encourages a "one-size-fits-all" approach rather than tailoring care management to states' needs. States requested that CMS review the consequences of this guidance.

| EXHIBIT 5. Massachusetts' Care Management Requirements Promote Continuity of Care |

|---|

|

Massachusetts' DSNP-based integration program, Senior Care Options (SCO), enrolls dual eligible beneficiaries age 65 and over. It is important for individuals enrolling in SCOs to maintain continuous access to any LTSS that they may be using. The state developed a checklist that inventories and categorizes the LTSS used by incoming SCOs enrollees. Plans can use this inventory to ensure that new SCO enrollees have their LTSS in place on the first day of their enrollment. This allows plans to coordinate a smooth transition of services and better prepares them to create care plans that address enrollees' needs.* * Before Contract Year 2016, Medicare Health Risk Assessments could not be performed until after a beneficiary's effective date of enrollment in a D-SNP (CMS MMCO, 2016a). |

4.3. Marketing

MA and federal Medicaid managed care marketing requirements differ in several ways (Soper & Weiser, 2014).[11] For example, although federal Medicare and Medicaid requirements related to unsolicited or cold-call marketing are similar, several states have more stringent beneficiary protections. Misalignments in Medicare and Medicaid marketing requirements create challenges for beneficiaries who typically receive separate marketing and educational materials (e.g., member handbooks, provider directories, and drug formulary lists) that do not consolidate Medicare-related and Medicaid-related information in one place.

Both states and CMS are working to better align and integrate marketing information and processes to help beneficiaries understand what services a health plan offers and to make more informed decisions about opportunities to enroll in an integrated DSNP program.[12] CMS is examining actions it could take without a change in regulations and has received input from states on what flexibilities would be beneficial. For example, CMS is exploring the feasibility of allowing integrated DSNP/MLTSS plans to use the marketing materials developed for the DSNPs participating in the Minnesota Demonstration to Align Administrative Functions for Improvements in Beneficiary Experience (CMS MMCO, 2016a). For their part, some states are using their MIPPA contracts with DSNPs to overcome misalignments in marketing requirements and material reviews by requiring DSNPs to submit marketing materials to the state at the same time as CMS so that the state can ensure that the Medicaid information provided is accurate.

The following two policy options could address some of the misalignments in Medicare and Medicaid marketing requirements:

-

Policy Option 3: States could modify some of their specific Medicaid managed care marketing restrictions to align with Medicare practices.

Rationale: This policy option would provide DSNPs with targeted opportunities to educate dual eligible beneficiaries on the value of enrolling in an aligned plan for Medicare and Medicaid. Enrollment of beneficiaries into aligned DSNPs and MLTSS plans is a goal of many states. However, to better facilitate this, states may need to reevaluate their Medicaid marketing requirements to ensure that plans can provide appropriate information about the benefits of aligned enrollment. Some states have stringent beneficiary protection requirements about when plans can contact enrollees and for what purpose. These restrictions could inadvertently prohibit Medicaid MLTSS plans from educating their enrollees about Medicare and the benefits of being in aligned DSNP and MLTSS plans.[13] For example, Arizona used to prohibit Medicaid managed care plans from conducting any marketing activity solely intended to promote enrollment. The state eventually modified its Medicaid restrictions around DSNP marketing to allow the plans to educate beneficiaries about the benefits of enrollment in an integrated product. Arizona state officials believe that aligned enrollment increased significantly because of this change and other beneficiary education activities conducted by the state. Exhibit 6 includes language from Arizona's MIPPA contract.

The states we spoke with agreed that there is value in examining whether their Medicaid marketing requirements conflict with their broader goals for aligned enrollment of dual eligible individuals. One state cautioned that if Medicaid marketing restrictions were modified, state Medicaid officials should closely monitor DSNP marketing materials, particularly those created for plans that use the material in multiple state markets. For example, states would need to ensure that descriptions of supplemental Medicare benefits available through DSNPs do not overlap with benefits that are already covered under the state's Medicaid program.

-

Policy Option 4: States could coordinate with DSNPs on education and outreach activities to help beneficiaries understand the value of integrated programs.

Rationale: States could take a more active role in helping to educate dual eligible beneficiaries about the benefits of integrated care programs and enrollment in aligned DSNP/MLTSS plans. One approach is for states to encourage plans to conduct more beneficiary outreach and education. To ensure that materials deliver a consistent message across plans about the benefits of aligned enrollment and Medicaid benefits, a state could develop model language or other written statements about the goals of its integrated care program.

In addition, some states like Arizona and New Jersey are sending educational materials directly to beneficiaries. Both state officials and DSNPs noted during the case study interviews that beneficiaries may have more confidence in materials sent to them by states than by health plans, and that many states may not be aware that this type of outreach is permitted under Medicaid regulations. The states we interviewed suggested that CMS could also support these efforts by issuing subregulatory guidance (e.g., a State Medicaid Director Letter) to remind states that they have the flexibility to directly engage beneficiaries.

See Appendix C for additional policy options related to marketing requirements.

| EXHIBIT 6. Arizona Uses Marketing Tools to Encouraging Aligned Enrollment |

|---|

|

A goal of Arizona's Medicaid agency is to have all dual eligible individuals enrolled in aligned DSNP and Medicaid plans, and the state has used several tools to accomplish this goal. The state requires that all Medicaid contractors operate a DSNP in the same service areas as their Medicaid plans. Moreover, the state permits DSNPs to tailor their marketing efforts to their own Medicaid MLTSS product members. Arizona's contract with DSNPs states, "[The State] encourages MA DSNP Plan to only direct market to individuals enrolled in MA DSNP Health Plan's AHCCCS Medicaid plan" (Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, 2016). This requirement promotes aligned enrollment by strongly suggesting that DSNPs market only to individuals who are already enrolled in their Medicaid products--essentially saying that one plan should not try to enroll other plan's Medicaid members in its own DSNP. In general, the state reports that this requirement has been effective in increasing the number of dual eligible individuals enrolled in aligned DSNP and Medicaid plans. Arizona also invested in educational outreach to promote aligned enrollment. It has worked with State Health Insurance Assistance Programs and state Aging and Disability Resource Center information and referral specialists to educate individuals about the benefits of DSNPs. Ongoing education has made beneficiaries more aware of the advantages of being in aligned plans for their Medicaid and Medicare benefits. |

4.4. Beneficiary and Provider Notices

Under both MA and Medicaid managed care programs, beneficiaries and providers have rights and protections related to access to services and financial liability. Both MA and state Medicaid agencies require that information about these rights and protections and plan benefits be communicated through written notices. MA plans, including DSNPs, send a variety of notices to beneficiaries to explain coverage and how to access care, including among others: (1) a Summary of Benefits; (2) the plan formulary; (3) a member handbook also called Evidence of Coverage--a document that provides information about covered benefits, any cost-sharing responsibilities, and other important coverage details; (4) an Annual Notice of Change--a document that informs beneficiaries about any changes in coverage, costs, or service area that will be effective in the following calendar year; and (5) provider and pharmacy directories.[14] A variety of other beneficiary notices are required related to denial of coverage for services and the opportunity to request appeals and file grievances. Additionally, MA plans are required to send notices to providers that explain payments and benefit coverage determinations. In integrated care programs, misalignments result from MA and Medicaid requiring different and sometimes conflicting content in these notices, particularly regarding beneficiary notices related to benefit determinations. For example, DSNPs must send advance notices to beneficiaries in skilled nursing facilities regarding when their Medicare benefits will be exhausted. This may be confusing for dual eligible beneficiaries whose coverage for the facility would continue under Medicaid.

The following policy option could address some of these misalignments:

-

Policy Option 5: HHS could work with states to develop a set of integrated beneficiary and provider materials exclusively for DSNP-based programs. In addition, CMS could allow for state review/comment on beneficiary notification materials before templates are finalized, changes to instructions are made, or guidance is issued by CMS to DSNPs on use of integrated notices.

Rationale: CMS recently issued a revised Integrated Denial Notice and a sample Summary of Benefits document that are used by DSNPs. However, the broad consensus among the states and plans was that integrated versions also are needed for the Evidence of Coverage, Annual Notice of Change, explanation of payment notices, formularies, provider directories, and other materials used by DSNPs. CMS staff have been working to make the current DSNP Annual Notice of Change and Evidence of Coverage documents more flexible. On February 21, 2017, CMS published a Federal Register notice asking for a second round of comments on standardized Evidence of Coverage and Annual Notice of Change documents (CMS, 2017d).[15] However, these standardized documents do not yet integrate both Medicare and Medicaid information.

The states we interviewed also asked for more input on the process that CMS uses to create integrated notices. For the new Integrated Denial Notice and Summary of Benefits document, CMS issued guidance, then held a comment period during which states and other stakeholders could give their feedback about the content of the notices and instructions. State officials believed that CMS should provide opportunities for greater state input into the early development of these integrated notices (perhaps by convening a workgroup), rather than soliciting their feedback after a fully formed draft was completed. The states expressed a desire for a more cohesive and comprehensive approach to communication with dual eligible populations through notices and other documents. Exhibit 7 illustrates how Massachusetts and Minnesota are using integrated materials to improve beneficiaries' experience of care.

See Appendix C for additional policy options related to beneficiary and provider notices.

| EXHIBIT 7. Massachusetts and Minnesota Use Integrated Materials to Improve Beneficiaries' Experience of Care |

|---|

|

Both Massachusetts and Minnesota have an integrated enrollment process for their DSNP-based integrated care programs. In Massachusetts, the Senior Care Options (SCO) program has a single enrollment form that incorporates the elements required by Medicare and Medicaid. Plans must submit the beneficiary's enrollment form to CMS and obtain approval for enrollment under Medicare before enrolling the beneficiary with the state for the Medicaid portion of SCO. Massachusetts DSNPs report that beneficiaries find this single enrollment process easy to understand, and the plans see it as the cornerstone to providing an integrated program experience for enrollees. Before the start of their demonstration, the FIDE SNPs in the Minnesota Senior Health Options program were already providing members with a single identification card, an integrated network of providers, and one member services phone number to assist enrollees. Now under the demonstration, Minnesota Senior Health Options plans can provide enrollees with a single member handbook that integrates information about Medicare and Medicaid benefits and processes and a single directory that lists all network Medicare and Medicaid providers. |

4.5. Data Collection and Quality Measurement

States need both Medicare and Medicaid data to effectively plan their integrated care programs for dual eligible beneficiaries and to assess the quality of care provided. Many state Medicaid agencies require that their DSNPs submit MA encounter data to the state, but the quality and completeness of these data vary, as does states' ability to analyze them (Integrated Care Resource Center, 2015). Starting in 2012, CMS required MA plans (including DSNPs) to submit encounter data, but CMS has not yet made these data available to states (Integrated Care Resource Center, 2015; GAO, 2014b, 2017).

DSNPs also have challenges in accessing the data they need. If a beneficiary is enrolled in one plan's DSNP product and another plan's MLTSS product or receives LTSS through the Medicaid fee-for-service system, the DSNP is essentially "blind" to the Medicaid services provided to that beneficiary. Care management is likely to be more effective when DSNPs know about all acute care services, care transitions, prescription drugs, and LTSS use.

The following policy option could provide greater access for DSNPs to needed data:

-

Policy Option 6: States could provide DSNPs with data on beneficiaries' Medicaid or Medicare service utilization history to support initial enrollee risk stratification and ongoing care management efforts.

Rationale: States could require plan submission of the beneficiary data needed to improve care coordination. For example, many states require DSNPs to submit encounter data, which states could then provide to MLTSS plans for dual eligible beneficiaries who are not in aligned plans. The converse is also possible: for states to provide DSNPs with data on their enrollees who are enrolled in non-aligned MLTSS plans or claims data for individuals who receive fee-for-service LTSS. Arizona provides these data to its DSNPs and MLTSS plans to support care coordination for their dual eligible beneficiaries. Exhibit 8 describes Tennessee's requirements for data exchange.

See Appendix C for additional policy options related to data collection and quality measurement.

| EXHIBIT 8. Tennessee Requires Data Exchange to Promote Care Coordination |

|---|

|

In Tennessee, all MLTSS plans must offer DSNPs, but the converse is not true, and three DSNPs in the state do not have companion MLTSS plans. Thus, it is possible for beneficiaries to enroll in one organization's DSNP and another organization's MLTSS plan. When dual eligible beneficiaries are enrolled in two plans for Medicare and Medicaid services, Tennessee requires DSNPs and TennCare CHOICES MLTSS plans to share Medicare and Medicaid encounter data, respectively, to promote care coordination. For example, each business day, DSNPs must report information on use of covered services, such as hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and other care coordination needs to the enrollee's CHOICES plan. In addition, DSNPs' care coordinators may reach out directly to the CHOICES MLTSS plan's care coordinator to collaborate around the beneficiary's discharge planning needs and care planning. The plans reported that it was technically difficult and costly to implement the information systems needed for this reporting process, but it greatly improved care coordination. |

4.6. Appeals and Grievances

When Medicare or Medicaid denies a beneficiary a service, in whole or in part, the individual has a right to appeal that determination. However, the two programs have different requirements and timelines for appeals (Kruse & Philip, 2015). In its annual reports to Congress, CMS MMCO has recommended legislation that would allow the Secretary of HHS to create an integrated appeals process for dual eligible beneficiaries enrolled in managed care plans providing both Medicare and Medicaid benefits (CMS MMCO, 2016b).

One significant challenge to implementing this is the requirement in Section 1852(g) of the Social Security Act that Medicare provide beneficiaries with a written notice when a request for a service is denied--even when that service is covered under Medicaid for dual eligible beneficiaries (SNP Alliance, 2016). CMS created an Integrated Denial Notice that all MA plans, including DSNPs and FIDE SNPs, must send to beneficiaries to explain why Medicare coverage was denied and how beneficiaries can appeal that decision. When a beneficiary is enrolled in an aligned DSNP/MLTSS plan or FIDE SNP, and the denied service can be covered under Medicaid, this information can be inserted by the plan in a free text field at the back of the multipage notice.

Despite this effort, state officials and health plans reported that beneficiaries, many of whom have low literacy skills or who are non-English speaking, continue to be confused and alarmed by receipt of the Integrated Denial Notice, because it may still appear that a service had been denied when it is covered under Medicaid. The result may be an increased volume of appeals and barriers to beneficiaries' access to care (Kruse & Philip, 2015). Although CMS has tried to mitigate this issue by making additional clarifications to the Integrated Denial Notice, this has not completely resolved the problem, and CMS has asked for public comment on the form and its instructions (CMS, 2016c).

-

Policy Option 7: HHS could change the notification process around benefit denial so that beneficiaries in aligned programs would not receive a denial notice if a service is denied by the MA plan but covered by Medicaid.

Rationale: The problem of having to issue a denial notice from the MA plan even when a service is covered by Medicaid is a major concern for both states and health plans. States and plans felt that an exception from sending denial notices should be made for enrollees in integrated plans whenever either Medicare or Medicaid will cover the benefit in question; however, this would require a change in statute. Ultimately, states and plans may be able to work around this problem if they move to serve dual eligible beneficiaries through FIDE SNPs, which can create an integrated benefits determination process that adjudicates service requests against a single, unified list of benefits rather than separate lists of Medicare and Medicaid benefits. In the meantime, HHS could provide plans with other options to communicate benefit determinations to enrollees in integrated care programs.

5. POLICY OPTIONS TO ENCOURAGE INVESTMENT IN DSNP-BASED APPROACHES TO INTEGRATION

The DSNP platform is still relatively new and there is still considerable opportunity to expand both the extent of DSNP service area coverage and the number of enrollees. In the previous section of this report, we presented policy options to improve the integration and alignment of Medicare and Medicaid administrative functions within DSNP-based integrated care programs. In this section, we focus on encouraging states and MA organizations to increase investment in DSNP-based approaches to integration through the exercise of policy options aimed at: (a) expanding DSNP enrollment and encouraging contractor alignment with Medicaid MLTSS plans; (b) supporting states and plans; and (c) refining MA payment policies.

5.1. Encouraging Aligned Enrollment

States have a range of DSNP contracting tools available to them, including program design strategies that could encourage aligned beneficiary enrollment and create the foundation for a more integrated approach. One important design strategy for states is to align DSNPs with their Medicaid managed care plans and encourage beneficiaries to enroll in these aligned DSNP/MLTSS plans so that one entity is responsible for coordinating and providing/arranging the full range of covered services.

States have significant flexibility to use their MIPPA contracts to increase aligned enrollment and promote care coordination. Several of the states with the highest DSNP enrollment--Arizona, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas--have or plan to launch MLTSS programs, and their MIPPA contracts require that DSNPs offer a companion MLTSS plan or that MLTSS plans offer a companion DSNP.

These aligned arrangements have potential benefits to enrollees because they may achieve high levels of administrative, financial, and clinical alignment (Verdier et al., 2016). Plans also see these arrangements as beneficial. In our case study interviews, DSNPs repeatedly told us that, for their MA organization corporate parents, the most desirable markets were in states where they had the opportunity operate Medicaid acute care, Medicaid MLTSS contracts, general MA and DSNP contracts. These multiple contracts may allow these organizations to realize economies of scope regarding their information systems, care manager training, or other administrative functions. It may also allow them to be more responsive to changes in a state's insurance landscape.

Another design option for states is to require DSNPs to become FIDE SNPs, which must coordinate LTSS and have procedures in place for administrative alignment of Medicare and Medicaid processes and policies. In FIDE SNPs, as with aligned DSNP/MLTSS plans, all care is coordinated by one entity.

Policy options that could help to encourage aligned enrollment in integrated health plans include the following:

-

Policy Option 8: HHS could lift the temporary moratorium on new approvals for "seamless conversion" submitted by DSNPs.

Rationale: Enrollment into the MA program is voluntary for Medicare beneficiaries. In contrast, states may choose either mandatory or voluntary enrollment in Medicaid managed care programs, although they need CMS waiver approval to require mandatory enrollment of certain populations (e.g., dual eligible and children with special health care needs). Consequently, dual eligible beneficiaries have the choice to enroll in different health plans for their Medicare and Medicaid benefits or they may remain in the Medicare fee-for-service program, but be required to enroll in a Medicaid health or MLTSS plan for services not covered by Medicare.

Despite the prohibition on mandatory enrollment in Medicare managed care, one tool that states and plans have had to enroll dual eligible beneficiaries in aligned Medicare and Medicaid plans is "seamless conversion." This process allows a DSNP to passively enroll Medicaid beneficiaries who are newly eligible for Medicare (i.e., just turning age 65 or at the end of the 2-year Social Security Disability Insurance waiting period), if they are already enrolled in that plan's companion Medicaid product. DSNPs in Arizona and Tennessee received CMS approval to use seamless conversion and have successfully enrolled several hundred beneficiaries a month into aligned plans. Exhibit 9 describes Arizona and Tennessee's use of the seamless conversion process.

Because of broad concerns about the adequacy of beneficiary protections, CMS put a temporary moratorium on approval of new requests to conduct seamless enrollment from all MA plans, including DSNPs, as of October 21, 2016, while it reviews current policies (CMS, 2016f).

The state officials with whom we spoke felt that seamless conversion is a valuable tool to promote aligned Medicare-Medicaid enrollment. They were concerned that applying this moratorium to DSNPs could limit dual eligible beneficiaries' opportunities to enroll in aligned plans and suggested that the moratorium hinders states' ability to better coordinate the current fragmented system of care for this vulnerable population. The states recommended that CMS remove the moratorium on seamless conversion for DSNPs, adding more beneficiary protections as needed--perhaps language to protect continuity of care, increased notification requirements, and stricter network adequacy standards for a DSNP to be approved--to do seamless conversion. States would like to be part of the discussion with plans and CMS about how to increase protections around and improve processes for seamless conversion.