ABSTRACT: Residential treatment facilities are a key component of states' behavioral health systems. They form part of the spectrum of treatment for both mental and substance use disorders (M/SUDs). Residential treatment includes providing health services or treatment in a 24-hour-a-day, 7-day-a-week structured living environment for individuals who need support for their mental health or substance use recovery before living on their own, but where inpatient treatment is not needed. Care is provided for limited periods of time and has the goal of preparing people to move into the community at lower levels of care.

Residential M/SUD treatment settings are governed almost exclusively by state statutes and regulations, rather than by federal laws. The Compendium describes regulatory provisions and Medicaid policy for residential treatment in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (hereafter states) and contains links to detailed summaries of state licensure and oversight standards and, separately, state Medicaid requirements. The supporting research examined residential treatment from a legal perspective, focusing foremost on state statutes and regulations, supplemented by other documents and input from states.

This report was prepared under contract #HHSP2332016000231 between HHS's ASPE/BHDAP and IBM Watson Health. For additional information about this subject, you can visit the BHDAP home page at https://aspe.hhs.gov/bhdap or contact the ASPE Project Officers at HHS/ASPE/BHDAP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201; Joel.Dubenitz@hhs.gov, Judith.Dey@hhs.gov.

DISCLAIMER: The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization. This report was completed and submitted on June 10, 2020.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION

- Methodology

- Organization of the Report

SECTION 2. OVERVIEW OF THE NONMEDICAID RESIDENTIAL TREATMENT REGULATIONS

- Domains Regarding Processes of Oversight

- Domains Regarding Facility Operations

SECTION 3. OVERVIEW OF STATE MEDICAID REQUIREMENTS FOR RESIDENTIAL TREATMENT

- Sources of State Medicaid Authority to Reimburse Residential Treatment

- Domains Regarding Processes of Oversight

- Domains Regarding Facility Operations

SECTION 4. DISCUSSION AND SYNTHESIS

- Oversight

- Operations

- Other Key Findings

APPENDICES

- APPENDIX A: Detailed Tables

- APPENDIX B: Separate State Summaries

- APPENDIX C: Detailed Methodology

LIST OF FIGURES

- FIGURE 1: Domains and Subdomains of Oversight and Operation of Residential Treatment Facilities

- FIGURE 2: Categories of Regulated Residential Treatment Facilities

- FIGURE 3: Number of States with Some Level of Identified Oversight of Residential Treatment Facilities

- FIGURE 4: Number of States with Inspections of Residential Treatment Facilities

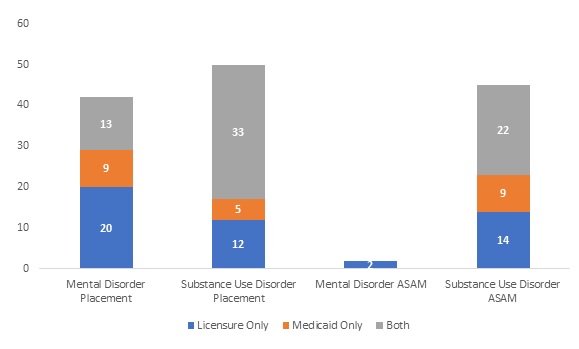

- FIGURE 5: Number of States with Provisions for Placement Criteria Specific to Residential Treatment

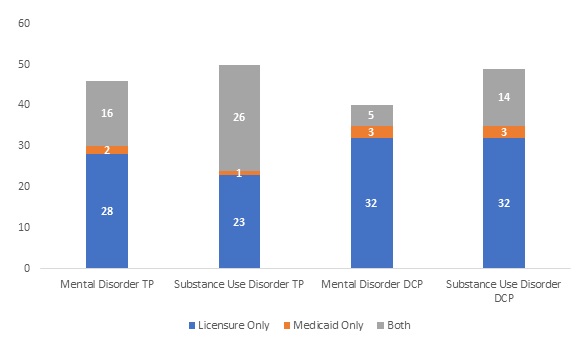

- FIGURE 6: Number of States with Provisions for Treatment and Discharge Planning Specific to Residential Treatment

- FIGURE 7: Number of States with Provisions for Aftercare Specific to Residential Treatment

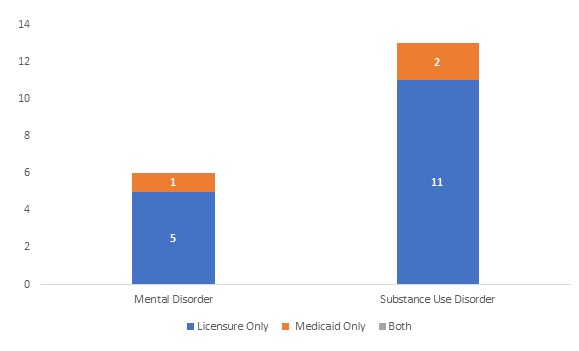

- FIGURE 8: Number of States with Requirements for Evidence-Based Treatments Specific to Residential Treatment

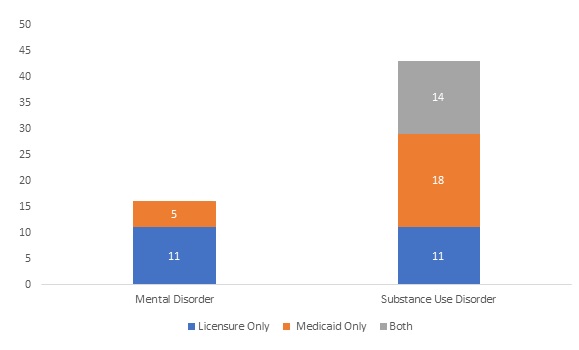

- FIGURE 9: Number of States with Provisions for MAT Specific to Residential Treatment

- FIGURE 10: Number of States with Provisions for Staffing Levels Specific to Residential Treatment

- FIGURE 11: Number of States with Provisions for QA/QI Specific to Residential Treatment

- FIGURE 12: Number of States with Provisions for Treatment of Co-occurring Disorders Specific to Residential Treatment

LIST OF TABLES

- TABLE 1: Number of States Regulated and Licensed by Funding Source

- TABLE 2: Number of States Using Different Approaches to Licensure and Other Oversight

- TABLE 3: Number of States with Requirements for Ongoing or Cause-Based Inspections

- TABLE 4: Number of States with Regulatory Provisions Regarding Wait Times

- TABLE 5: Number of States by Staffing Standards for Licensure

- TABLE 6: Numbers of States by Training Requirements for Licensure

- TABLE 7: Residential Treatment Facilities Using Workforce Quality Assurance Practices as Standard Operating Procedure, Mental Health 2010, SUD 2013

- TABLE 8: Number of States Regulating Placement Criteria

- TABLE 9: Number of States with Requirements Regarding Treatment or Discharge Planning or Aftercare Services

- TABLE 10: Number of States with Regulations Regarding Services

- TABLE 11: Number of States with Regulations Regarding MAT Specific to Residential Treatment

- TABLE 12: Number of States with Regulations Regarding Service Recipient Rights

- TABLE 13: Number of States with QA/QI Regulations

- TABLE 14: Number of States with Governing Body Regulations

- TABLE 15: Number of States with Regulations Regarding Special Populations

- TABLE 16: Sources of State Medicaid Authority to Reimburse Behavioral Health Treatment in IMDs, Number of States

- TABLE 17: Number of States With Different Categories of Residential Mental Disorder Treatment Facilities That Can Enroll in Medicaid

- TABLE 18: Number of States with Different Categories of Residential SUD Treatment Facilities That Can Enroll in Medicaid

- TABLE 19: Number of States with Different Processes of Medicaid Enrollment Fully or Partially Present

- TABLE 20: Number of States with Medicaid Requirements for Staffing in Residential Facilities

- TABLE 21: Number of States with Medicaid Requirements for Staff Training in Residential Facilities

- TABLE 22: Number of States with Medicaid Requirements for Placement in Residential Facilities

- TABLE 23: Number of States with Medicaid Requirements for Treatment and Discharge Planning, Care Coordination, and Aftercare in Residential Treatment

- TABLE 24: Number of States with Medicaid Requirements for Services in Residential Facilities

- TABLE 25: Number of States with Medicaid Requirements for MAT in Residential Facilities

- TABLE 26: Number of States with Medicaid Requirements for QA/QI

- TABLE 27: Number of States with Medicaid Requirements Related to Special Populations

- TABLE A1: Categories of Regulated Residential Mental Health Treatment Facilities

- TABLE A2: Categories of Regulated Residential SUD Treatment Facilities

- TABLE A3: Regulation of Residential Mental Health Treatment Facilities Based on Funding

- TABLE A4: Regulation of Residential SUD Treatment Facilities Based on Funding

- TABLE A5: Extent of Regulation of Residential Mental Health and SUD Treatment Facilities by State

- TABLE A6: Organization of Oversight Within States

- TABLE A7: Processes of Licensure and Basic Oversight for Mental Health

- TABLE A8: Processes of Licensure and Basic Oversight for Substance Use

- TABLE A9: Ongoing or Cause-Based Monitoring

- TABLE A10: Wait Time Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A11: Staffing Standards for Residential Facilities for Mental Health

- TABLE A12: Staffing Standards for Residential Facilities for Substance Use

- TABLE A13: Staff Training Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A14: Placement Standards for Residential Facilities for Mental Health

- TABLE A15: Placement Standards for Residential Facilities for Substance Use

- TABLE A16: Treatment Planning, Discharge Planning, and Aftercare Standards for Residential Facilities for Mental Health

- TABLE A17: Treatment Planning, Discharge Planning, and Aftercare Standards for Residential Facilities for Substance Use

- TABLE A18: Treatment Services Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A19: Requirements Specific to MAT in Residential Facilities

- TABLE A20: Service Recipient Rights--Grievances and Complaints Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A21: Service Recipient Rights--Restraint and Seclusion Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A22: QA/QI Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A23: Governance Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A24: Requirements Specific to Special Populations for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A25: Source of State Medicaid Authority to Reimburse Residential Mental Health Treatment in IMDs

- TABLE A26: Source of State Medicaid Authority to Reimburse Residential SUD Treatment in IMDs

- TABLE A27: Categories of Residential Mental Health Treatment Facilities That Can Enroll in Medicaid

- TABLE A28: Categories of Residential SUD Treatment Facilities That Can Enroll in Medicaid

- TABLE A29: Processes of Medicaid Enrollment

- TABLE A30: Medicaid Staffing Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A31: Medicaid Staff Training Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A32: Medicaid Placement Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A33: Medicaid Treatment Planning, Discharge Planning, Care Coordination, and Aftercare Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A34: Medicaid Treatment Services Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A35: Medicaid Requirements Specific to MAT in Residential Facilities

- TABLE A36: Medicaid QA/QI Standards for Residential Facilities

- TABLE A37: Medicaid Requirements Specific to Special Populations for Residential Facilities

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IBM Watson Health prepared this report under contract to the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) (HHSP2332016000231HHSP23337003T). The authors appreciate the guidance of Judy Dey and Joel Dubenitz (ASPE). Jesse Roberts (IBM Watson Health), Wendolyn Ebbert (Brandeis University), and Danielle Strauss (Brandeis University) contributed to important phases of data collection. Mary Beth Schaefer, Paige Jackson, and Kristin Schrader (IBM Watson Health) provided editorial support. Special thanks are owed to Ted Lutterman and Kristin Neylon at NRI and to Melanie Whitter and Marcia Trick at National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors (NASADAD), both for their subject matter expertise and their invaluable assistance in contacts with states for validation of the primary summaries. We also thank our key informants: Lindsey Browning, the National Association of Medicaid Directors; Pamela Greenberg, the National Association of Behavioral Health and Wellness; Dr. Joe Parks, the National Council for Behavioral Health; Ted Lutterman, NRI; and Melanie Whitter and Rick Harwood, NASADAD.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of ASPE or HHS. The authors are solely responsible for any errors.

ACRONYMS

The following acronyms are mentioned in this report and/or Appendix A and Appendix C. Appendix B has an extensive acronym list that is not included here.

| ASAM | Americans Society of Addiction Medicine |

|---|---|

| ASO | Administrative Service Organization |

| ASPE | HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation |

| AUD | Alcohol Use Disorder |

| CHIP | Children's Health Insurance Program |

| CMS | HHS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

| COA | Council on Accreditation |

| CON | Certificate of Need |

| DSH | Disproportionate Share Hospital |

| HHS | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

| IDU | Injection Drug Use |

| IMD | Institution for Mental Disease |

| IRTS | Intensive Residential Treatment Services |

| LOCUS | Level of Care Utilization System |

| M/SUD | Mental and Substance Use Disorders |

| MACPAC | Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission |

| MAT | Medication-Assisted Treatment |

| MCE | Managed Care Entity |

| N-MHSS | National Mental Health Services Survey |

| N-SSATS | National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services |

| NASADAD | National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors |

| OUD | Opioid Use Disorder |

| QA/QI | Quality Assurance/Quality Improvement |

| PPW | Pregnant and Parenting Women |

| R/S | Restraint/Seclusion |

| SAMHSA | HHS Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

| SMI | Serious Mental Illness |

| SUD | Substance Use Disorder |

| SUPPORT | Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for patients and communities act |

| TJC | The Joint Commission |

| WM | Withdrawal Management |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Background

Residential treatment facilities are a key component of states' behavioral health systems. They form part of the spectrum of treatment for both mental and substance use disorders (M/SUDs). Residential treatment involves providing health services or treatment in a 24-hour-a-day, 7-day-a-week structured living environment for individuals who need support for their mental health or substance use recovery before living on their own, but where inpatient treatment is not needed. Care is provided for limited periods of time and has the goal of preparing people to move into the community at lower levels of care.[1]

Recently, more attention has been paid to these intermediate levels of care for persons with M/SUD. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has expanded efforts to ensure a broader continuum of care for both M/SUD, including demonstration opportunities for state Medicaid programs to receive federal matching funds for an expanded range of services that include residential treatment. On July 27, 2015, and November 1, 2017, CMS announced opportunities for states to design new substance use disorder (SUD) service delivery systems using the Section 1115 demonstration authority under Medicaid.[2, 3] Among other things, these opportunities enabled approved states to expand reimbursement for residential SUD treatment. More recently, on November 13, 2018, CMS announced similar opportunities regarding service delivery systems for adults with a serious mental illness (SMI). Improving quality is a key component of those demonstrations.[4]

Residential M/SUD treatment settings are governed almost exclusively by state statutes and regulations, rather than by federal laws. This Compendium's purpose is to inform behavioral health treatment policy by providing detailed information about each state's approach to regulating and funding services in residential M/SUD treatment settings. The Compendium describes regulatory provisions and Medicaid policy for residential treatment in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (hereafter states) and contains links to detailed summaries of state licensure[5] and oversight standards and, separately, state Medicaid requirements. The supporting research examined residential treatment from a legal perspective, focusing foremost on state statutes and regulations, supplemented by other documents and input from states.

In reading this Compendium, however, it is critical to remember that states may use other levers of oversight in addition to regulations, such as contracts with facilities receiving state funds, contracts between the state and Medicaid managed care entities (MCEs) or individual providers, and contracts between MCEs and individual providers. State licensure manuals and state Medicaid policies also are used to define provider responsibilities. Additionally, all state Medicaid programs require appropriate licensure of providers, hence, incorporating by that mandate all relevant requirements for obtaining and maintaining licensure.

Methodology

As a precursor to the collection and synthesis of data drawn primarily from state law, we conducted an environmental scan[4] and interviewed experts in the field. We then examined relevant statutes and regulations governing behavioral health treatment and licensing or certification for the 51 states, as well as examining state Medicaid requirements regarding residential treatment. The domains examined for both licensure and Medicaid relate to standards: (1) regarding processes of oversight such as regulation and licensure; and (2) related to facility operation that are conditions of operation and licensure.

The primary focus of this Compendium is residential M/SUD treatment for adults ages 21-64 years. For this Compendium, we define residential treatment as clinical treatment services for M/SUD provided in a 24-hour living environment, including withdrawal management residential facilities. This Compendium excludes residential settings that predominantly serve people with intellectual and other developmental disabilities or settings that are forensic, correctional, or inpatient.

Research Findings

Processes of oversight. From state to state, regulations and Medicaid policy vary dramatically in how states define residential treatment settings. The largest category of mental health residential facilities among states comprises those that are crisis focused. In the realm of SUD residential treatment, the categories identified in the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) criteria as Level 3 residential and withdrawal management facilities form a substantial portion of state facility types. Other states focus on, for example, the duration of stay or the condition treated. Regulatory processes sometimes vary between states by funding type (e.g., publicly-funded, Medicaid-enrolled, private facilities). In addition, many states have multiple agencies or subagencies overseeing and/or licensing treatment facilities, including separate entities regulating mental disorder versus SUD treatment, separate entities overseeing Medicaid-enrolled facilities, and layers of regulation that may include a state behavioral health agency, a state public health department, and a state Medicaid agency. Mental health residential treatment is less likely than SUD residential treatment to be regulated, although determining which facilities in the states are unregulated is difficult. Doing so requires a thorough understanding of which types of facilities are regulated. From that, one can conclude that certain facility types are or may be unregulated, if they exist in the state.

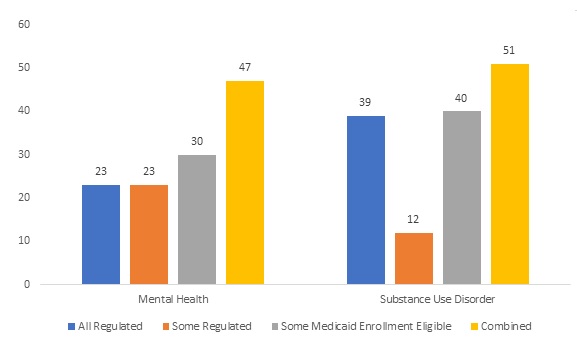

The licensure process can be quite complex and entail many requirements. Accreditation by an independent body is somewhat unlikely to be required; it is more likely that a state will confer "deemed status" on facilities that are accredited, absolving them of certain licensure requirements. Often the requirement being excused relates to some portion of licensure inspections, most often at renewal. Viewing inspections as an indicator of the state's ability to monitor facilities over time, whether as part of licensure, renewal, or for cause, we closely examined the extent to which states have some provision for inspection, whether through licensure and related standards or as part of Medicaid enrollment. We found such requirements for 47 and 50 states, for mental disorder and SUD treatment, respectively.

Standards for facility operations. This study examined many aspects of facility operation that may be addressed via regulation. We found that some, such as wait time requirements for placement, are often not included in regulations but may be found in contracts or on agency websites. Other operational considerations are frequently addressed in a regulatory context. Some primary findings are summarized below.

Placement in the appropriate setting and level of care is important to ensure that patients receive the care they need. We examined whether there were specific state criteria for placement and/or assessment, to ascertain whether placement in a given residential facility type is suitable for the individual seeking treatment. Specific placement criteria for residential treatment facilities are the norm, derived from a combination of licensure-related and Medicaid requirements; 42 and 50 states were found to include such requirements for mental disorder and SUD residential treatment, respectively. As might be expected, required use of the ASAM Patient Placement Criteria was nearly exclusively limited to residential SUD treatment. A total of 45 states specifically use the ASAM criteria for placement in SUD treatment; many of those 45 states have Section 1115 Institution for Mental Diseases (IMD) demonstrations. Many states also have, in addition to standards of placement, criteria for continued stay and/or discharge.

States are more likely to include treatment planning and discharge planning requirements in licensure and related standards than they are to include them as Medicaid requirements. Documentation examined revealed that treatment planning requirements were included for 46 and 50 states, respectively, for mental disorder and SUD residential treatment. Nearly as many states included discharge planning requirements: 40 and 49 states for mental disorder and SUD treatment, respectively. These high numbers indicate the importance placed on appropriately planning treatment and the provision for ongoing treatment and support after discharge, preferably beginning early in the treatment process.

Even though discharge planning requirements are common, state standards for the actual provision of aftercare services by a residential facility as a bridge to subsequent care or follow-up after discharge from a residential facility are rare. Six and 13 states include such requirements for mental disorder and SUD residential treatment, respectively, primarily in licensure or other nonMedicaid standards and most frequently requiring follow-up rather than aftercare.

Ensuring the provision of evidence-based or best practice treatment is crucial to maintaining high-quality residential services for M/SUDs. In addition to assessments related to placement, treatment planning, and coordination of care, treatment services in the form of psychosocial and medication treatment are key components of residential treatment. Although states vary in the extent to which they elaborate, in the SUD treatment realm, the ASAM Level 3 standards increasingly are adopted to guide state treatment requirements, driven in part by approved Section 1115 Medicaid demonstrations. These standards set criteria for different levels of residential and withdrawal management treatment. Two discrete indicators of service requirements that were examined as part of this study were requirements for use of: (1) evidence-based practices generally; and (2) medication-assisted treatment[6] (MAT) specifically, in residential treatment. Regarding the first, we found that SUD residential treatment facilities are most likely to have requirements for evidence-based practices, with 43 out of 51 states including some form of requirement, most commonly MAT. In contrast, only 16 states, in total, incorporated requirements specific to evidence-based practices for residential mental health treatment. Regarding MAT, requirements were more commonly specific to SUD treatment facilities, with a total of 39 states having SUD licensure-related and/or Medicaid-related requirements in place in regulations or other documents specific to residential treatment. A significant portion of the Medicaid requirements reflect the existence of Section 1115 demonstrations.

Staffing standards may include requirements regarding hiring, credentialing, training, documentation of employment requirements or practices, and staffing levels, among other things. As one indicator of state involvement in staffing standard-setting, we looked at staffing levels. Adequate staffing levels are needed to ensure quality treatment and safety in 24-hour mental disorder and SUD treatment settings. Among requirements for mental health residential treatment, 30 states had general requirements for "adequate" or "sufficient" staffing and 27 had specific ratio requirements. For SUD residential treatment, 41 states had general requirements and 34 had specific ratio requirements. Most such requirements sprang from licensure and other nonMedicaid standards.

The scope and nature of quality assurance/quality improvement requirements applicable to residential M/SUD treatment vary considerably, but some form of explicit requirement imposed on facilities is common (e.g., written quality improvement plan, use of data for quality improvement purposes). This is truer for SUD than for mental disorder treatment and generally originates in licensure and related oversight standards rather than in state Medicaid requirements. We identified 38 and 48 states that impose some such requirement for residential mental disorder and SUD treatment facilities, respectively.

We looked at two discrete aspects of service recipient rights, related to: (1) the right to voice grievances, taken as an indicator of the ability of service recipients to enforce their rights in general; and (2) rights related to restraint and seclusion, because restraint and seclusion affect safety and dignity. The first--the right to voice grievances--is most commonly mandated, with 37 and 42 states having such requirements for mental disorder or SUD treatment, respectively, as part of licensure standards. In contrast, rights regarding restraint or seclusion were found for mental disorder or SUD treatment in 42 and 37 states, respectively.

Governance standards are elaborate in some states and nonexistent in others. They may be integrated into licensure requirements, for example, as part of what facilities must demonstrate in their application. They also may be a more general part of state regulations governing operating requirements. They may be as simple as requiring information at licensure and the development and maintenance of policies and procedures, or they may include detailed requirements regarding different areas of facility internal structure and oversight. Some form of governance requirements were located in licensure standards in 36 states regarding mental disorder residential treatment and in 41 states regarding SUD residential treatment.

States identify a range of special populations to whom they wish to target services. This is truer of SUD treatment than of mental disorder treatment and often stems from block grant requirements. The two most common populations identified, particularly for SUD residential treatment, are those with co-occurring M/SUDs and pregnant and parenting women or parents of dependent children. Regarding the latter, many states have specific requirements for residential facilities in which pregnant women, parenting women, and/or families with dependent children may receive treatment, including educational, health, and safety requirements for children. Regarding standards applicable to treating those with co-occurring M/SUDs, although additional requirements may exist in contracts or policy documents, in the documentation reviewed, we found nearly twice as many states with licensure-related requirements for treatment of co-occurring M/SUD disorders stemming from the SUD side of state policy (29 states) compared with mental disorder residential treatment (15 states). Many of the former reflect requirements based in Section 1115 demonstrations but states have, apart from that, often sought to ensure that SUD-focused treatment facilities address mental disorders as well.

Other key findings. This research also produced at least four overarching additional findings.

-

State Medicaid programs all incorporate some requirement for appropriate licensure within the state, for facilities providing residential treatment. This allows state Medicaid regulations to be less exacting in many cases, because they rely on already existing standards.

-

Section 1115 demonstrations, as well as the ASAM criteria, have been critical to strengthening regulation of residential SUD treatment. The state structure and oversight of residential mental disorder treatment has not kept pace.

-

We did not include all residential settings in this study. For example, small group homes and recovery housing, where clinical treatment is not integrated into the residence, were excluded. Such facilities may or may not be regulated or licensed. They may be providing very valuable benefits to their residents or services of unknown quality.

-

States have diverse ways of overseeing M/SUD treatment. Some rely heavily on published statutes and regulations. This results in clearly established, transparent requirements that lay out the legal basis for oversight, licensure, and/or Medicaid enrollment. It also may result in requirements being established that can be difficult to change when flexibility or adaptation is needed. Comparable to promulgated regulations are state Medicaid demonstration or state plan documents that have been approved by CMS, which are binding and have the benefit of transparency and certainty, provided rapid change is not required. Some states rely more heavily on contractual requirements, also binding but often less transparent. States also use agency licensing or standards manuals and, for Medicaid, provider manuals or other policy documents. Theoretically, these may be less binding on providers unless, as is often the case, they are incorporated by reference into state statutes, regulations, or provider agreements. This approach has the benefit of requiring only that the manual or other document be amended and published to alter requirements when doing so may be time sensitive. However, hurdles can exist that impede public access to such documents.

Conclusions

Regulation and oversight of residential treatment is a patchwork, and identification of unregulated facilities is an imprecise exercise. Regulation of SUD treatment is more pronounced and somewhat more consistent across states than is regulation of mental disorder treatment, although both have room for improvement. This difference is often driven by the fact that many of the SUD treatment requirements are a result of Medicaid demonstration/waiver requirements that also appear to be seeping into SUD licensure and other nonMedicaid oversight standards. The inclusion of requirements as part of Medicaid demonstrations, such as requirements regarding provision of MAT in residential treatment, even if only directly applicable to certain facilities or certain populations, means that it is more likely that other facilities and individuals in the state will experience spillover as MAT becomes more widely available. This suggests that, if more states obtain approval for Section 1115 demonstrations that affect reimbursement of mental disorder treatment in IMDs in accordance with the November 2018 State Medicaid Directors Letter,[4] it is possible that similar strides could take place for mental disorder residential treatment. Additionally, the Section 1115 demonstrations are laboratories for innovation that may spread best practices to other states. Consideration of how to create more such laboratories for the treatment of SMI is an important next step.

SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION

Residential treatment facilities are a key component of states' behavioral health systems. They form part of the spectrum of treatment for both mental and substance use disorders (M/SUDs). Residential treatment involves providing health services or treatment in a 24-hour, 7-day a week structured living environment for individuals who need support for their mental health or substance use recovery before living on their own, but where inpatient treatment is not needed. Care is provided for limited periods of time and has the goal of preparing people to move into the community and into lower levels of care.[1]

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA's) National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS) for 2017 reported that the United States had 856 organizations providing residential mental health treatment for adults. Eighty percent of adult residential treatment facilities offered psychotropic medications, 65% offered group psychotherapy, 60% offered individual psychotherapy, and 58% offered cognitive behavioral therapy.[7] More than 80% of these facilities provided only mental health services, whereas 19% also provided substance use services. Most facilities were nonprofit and accepted Medicaid payments.[8]

The SAMHSA National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) survey for 2017 found that approximately 3,125 organizations were providing residential substance use disorder (SUD) treatment in the United States.[9] Among all residential substance use facilities, about 23% of these facilities had fewer than 13 residential beds, 59% of facilities had more than 18 residential beds, and 18% had 48 or more residential beds.[10] Most residential SUD treatment facilities were nonprofit. About half accepted Medicaid and more than 60% accepted private insurance.[9]

Recently, increased attention has been paid to these intermediate levels of care for persons with M/SUD. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has expanded efforts to ensure a broader continuum of care for both M/SUD, including demonstration opportunities for state Medicaid programs to receive federal matching funds for an expanded range of services that include residential treatment. On July 27, 2015, and November 1, 2017, CMS announced opportunities for states to design new SUD service delivery systems using the Section 1115 demonstration authority under Medicaid.[2, 3] Among other things, these enabled approved states to expand reimbursement for residential SUD treatment. More recently, on November 13, 2018, CMS announced similar opportunities regarding service delivery systems for adults with a serious mental illness (SMI).

Improving access to needed treatment and quality care are key components of the Section 1115 demonstrations.[4] For SUD treatment generally, this has been shaped by the demonstration requirements that treatment follow aspects of the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) treatment criteria, and the ASAM criteria have increasingly made their way into state Medicaid and nonMedicaid requirements as a result. The ASAM criteria were developed to improve assessment, treatment and recovery services, and to match patients to the appropriate level of treatment. For adult residential treatment, this includes the following levels:

- Level 3.1. Clinically Managed Low-Intensity Residential Services.

- Level 3.3. Clinically Managed Population-Specific High-Intensity Residential Services (formerly Medium-Intensity).

- Level 3.5. Clinically Managed High-Intensity Residential Services.

- Level 3.7. Medically Monitored High-Intensity Inpatient Services (which, in many states, are offered in residential settings).

- Level 3.2-WM. Clinically Managed Residential Withdrawal Management.

- Level 3.7-WM. Medically Monitored Inpatient Withdrawal Management (in many states, offered in residential settings).

A similar system of levels of care and placement criteria exists for mental health treatment in the Level of Care Utilization System (LOCUS):

- Level 5. Medically Monitored Residential Services.

- Level 6. Medically Managed Residential Services.[11]

According to expert interviews, states are increasingly requiring the LOCUS for placement purposes in their contracts with providers or managed care entities (MCEs).

Control and oversight of residential behavioral health treatment settings, including with regard to placement, quality, treatment services, and other matters, however, are fundamentally governed by state laws and regulations, and these vary by state. Indeed, some states may have multiple sets of oversight, licensure, or certification requirements, and some licensure standards also may require accreditation or provide for optional accreditation. Thus, accreditation by an independent accrediting body such as the Joint Commission (TJC), the Commission on Accreditation for Rehabilitative Facilities, or the Council on Accreditation (COA) can provide yet another layer of oversight and inspection, beyond that carried out by the states. This Compendium describes regulatory provisions and Medicaid policy for residential treatment in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (hereafter states). Appendix B contains links to detailed summaries of state licensure and oversight requirements and state Medicaid requirements, including Section 1115 demonstration requirements.

The primary focus of this Compendium is residential M/SUD treatment for adults ages 21-64 years. As more fully explained under Methodology, this Compendium does not include residential settings that predominantly serve people with intellectual and other developmental disabilities or settings that are forensic or correctional. It also does not include residential placements that are not required to include some form of clinical psychosocial treatment for mental disorders or SUDs, although withdrawal management facilities are included. States use many terms for residential treatment settings. This Compendium uses the term residential treatment as a generic label that encompasses all state licensure categories; the state summaries use each state's specific licensure or certification term(s).

The Compendium's purpose is to inform residential behavioral health treatment policy by providing detailed information about each state's approach to regulating and funding services in residential behavioral health treatment settings. In reading this Compendium, however, it is critical to remember that states may use other levers of oversight in addition to regulations, such as contracts with facilities receiving state funds, contracts between the state and Medicaid MCEs or individual providers, or contracts between MCEs and individual providers. State licensure manuals and state Medicaid policies also are used to define provider responsibilities. Additionally, all state Medicaid programs require appropriate licensure of providers, incorporating by that mandate all relevant requirements for obtaining and maintaining licensure.

Methodology

As a precursor to the collection and synthesis of data drawn primarily from state law, we conducted an environmental scan and interviewed experts in the field. Relevant articles and other source documents were reviewed, synthesized, and summarized in the environmental scan, which is published separately.[12] In addition, we identified and interviewed a number of subject matter experts who are recognized in the acknowledgments section of this Compendium.

On the basis of findings from the environmental scan[12] and interviews with experts, we developed a template that provided the coding structure for data collected throughout the project. Relevant statutes and regulations governing behavioral health treatment and licensing or certification from 51 jurisdictions were reviewed and abstracted into the data collection template. We prepared detailed state summaries of: (1) licensure standards; and (2) Medicaid requirements by synthesizing the abstracted information (see Appendix B).

Several parameters were placed around the scope of data collection to ensure consistency:

- Residential treatment was defined as clinical treatment services provided in a 24-hour living environment, including withdrawal management treatment.

- Only residential treatment facilities for adults were included; thus, treatment specific to children or adolescents was excluded.

- We excluded facilities that are associated with the criminal justice system or that are in inpatient settings.

- Medicaid-specific requirements are included separately for each state.

The state summaries that resulted from data collection regarding licensure were shared with the individual states for validation. On the basis of input from the states, the summaries were revised as necessary. In some instances, state personnel provided additional sources of information beyond the statutes and regulations and, to the extent that it was pertinent to the study, we included that information. Among other things, this included information in certification or licensure manuals and written input from state staff. All publicly available documents on which we relied are referenced in the state summaries.

In the summaries of state Medicaid requirements, we primarily relied on state Medicaid regulations and Section 1115 demonstration documents. Where necessary, these were supplemented with additional sources. The relative absence of certain requirements in state Medicaid regulations, however, does not mean that Medicaid programs do not have service requirements in provider agreements with Medicaid or MCEs, provider manuals, or elsewhere. Similarly, some states may passively rely on the presence of licensure requirements to ensure that service standards are in place.

Throughout the study, we used a legal mapping framework. This approach provides structured steps to follow in reviewing and compiling information from legal documents. In addition, we coordinated with other federal efforts on this topic and leveraged efficiencies available through ongoing parallel efforts, such as those being led by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC).[13] By integrating input from leaders in this field throughout the course of the project, as well as applying a rigorous legal mapping framework for abstraction and synthesis, we generated accurate information to disseminate widely and inform next steps in addressing capacity for M/SUD treatment across the continuum of care (see Appendix C for more detailed description of the methods for this Compendium).

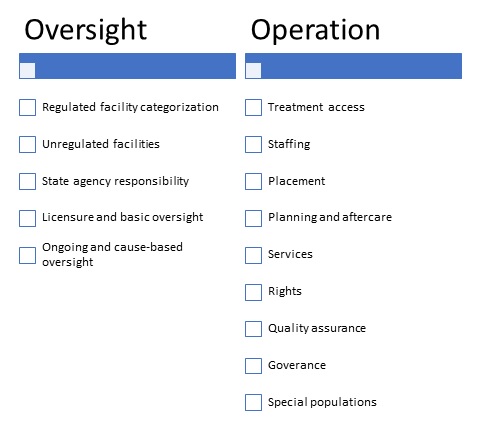

Conceptual framework. This study examines residential treatment from a legal perspective, focusing foremost on state statutes and regulations. The domains examined relate to regulatory standards: (1) regarding processes of oversight such as regulation and licensure;[14] and (2) related to facility operation that are conditions of operation and licensure. Figure 1 identifies those domains and subdomains, all of which are described and discussed more fully in Section 2 of this Compendium. Complementing this, Section 3 uses some but not all of the same domains and subdomains in the context of state Medicaid requirements.

Study limitations. One limitation is that a full understanding of a state's oversight of residential treatment facilities requires examination of more than the state statutes and regulations, which provide only a partial picture of how oversight works in reality. Those statutes and regulations are, however, the legally enforceable mechanisms that govern facilities, and they are publicly available to all stakeholders. Additional information, however, could be gleaned from provider or MCE contracts, additional policy documents, or from an understanding of how regulations are enforced, or not, in practice. Another limitation is that the summaries reflect state law at a single point in time. Statutes and regulations are amended on an ongoing basis. This means that, at the point of publication of this Compendium, some statutes and regulations will have been amended, repealed, or replaced, rendering some portion of the summaries no longer accurate.[15] Last, because data collection requires deliberate selection of some characteristics over others and some components of regulatory oversight (such as building, fire, and zoning requirements) were not included, the scope of these summaries cannot be considered exhaustive.

| FIGURE 1. Domains and Subdomains of Oversight and Operation of Residential Treatment Facilities |

|---|

|

Organization of the Report

Section 2 provides an overview of state regulatory provisions covering the two broad domains and 14 subdomains introduced in the study framework, including primary implications of those findings. Section 3 contains an overview of state Medicaid funding for services furnished in these settings and related policies, including primary implications of those findings. Section 4 discusses the key trends identified in this Compendium, including discussion of the ways in which state licensing regulations and Medicaid requirements often complement each other. Appendix A includes detailed tables showing results in each subdomain by state, and Appendix B contains links to each of the individual state licensing and Medicaid summaries. Appendix C contains a more complete methodology than that in Section 1 of this Compendium.

SECTION 2. OVERVIEW OF THE NONMEDICAID RESIDENTIAL TREATMENT REGULATIONS

The two primary domains examined relate to: (1) regulatory standards regarding processes of oversight such as regulation and licensure; and (2) regulatory standards regarding facility operation that are conditions of operation and licensure. Each domain and subdomain (hereinafter domains) is addressed in turn below. We provide an explanation for why each domain is important to the regulation and oversight of residential treatment, what each domain encompasses, and a discussion of major findings.

Domains Regarding Processes of Oversight

Domains regarding processes of oversight include categorization of regulated facilities, identification of unregulated facilities, state agency responsibility for oversight, processes of licensure and basic oversight, and processes of ongoing oversight.

| FIGURE 2. Categories of Regulated Residential Treatment Facilities |

|---|

|

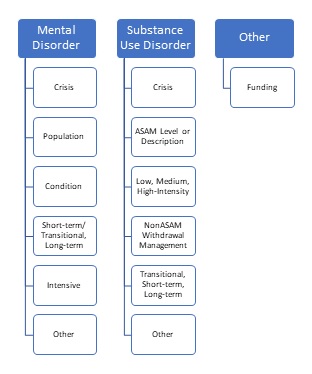

Categorization of regulated facilities. State regulations identify residential treatment facilities in many ways. Those identified in the regulations, therefore, had to be categorized in order to understand and describe the scope of what is regulated in a given state. We began with a distinction between mental disorder and SUD treatment facilities, given the historic bifurcation of the two systems,[16] and with an understanding that some states would distinguish facilities on the basis of their sources of funding. Further categorization was not possible until after data collection, and this post hoc categorization was primarily intended to identify major categories of residential treatment as often viewed by the states. Figure 2 depicts the categories ultimately used.

We discuss separately below the categorization for regulated mental disorder and SUD residential treatment, as well as categorization by funding source. It is apparent that the landscape of regulated residential treatment in the states is as diverse as the states themselves. There are many differences among states, as further discussed below.

-

Mental disorder residential treatment. The largest group of mental disorder residential facility types were those labeled as some form of specialized crisis facility. At least 32 states have such facilities serving individuals with mental disorders, some of which also serve clients with SUDs.[17] Detail by state is included in Table A1 and in the relevant state summaries (Appendix B). In addition to the states that regulate crisis facilities as such, some simply incorporate crisis services into other types of residential facilities. A much smaller number of states regulate facilities within the other identified categories. Nine states included facilities labeled as either short-term or transitional. The time period covered by this label varies considerably (e.g., 90 days or less for short-term facilities in Florida vs. 12 months for transitional facilities in California).[18, 19] Six states expressly label mental health facilities as long-term and, again, what is considered long-term varies by state (e.g., 60 days or greater average length of stay in Florida vs. 18 months maximum in California).[20, 21] Three states label or define certain facilities as intensive. An example of an intensive mental disorder residential treatment facility is the Minnesota Intensive Residential Treatment Services (IRTS).[22] In addition to states with facilities specific to women, which are addressed in the section of this Compendium regarding special populations, at least three states have facilities focused on specific populations. One example is Virginia, which has separate regulations specific to acute gero-psychiatric residential services.[23] A similarly small number of states identify residential facilities for individuals with specific conditions, in particular, three for eating disorders.[24] Finally, at least 31 states identify residential mental disorder treatment with nonspecific labels that do not fit our categories (e.g., Mental Health Centers, Residential Treatment Programs, Specialized Treatment Facilities). In addition, four states that do not identify any regulated residential mental disorder treatment facility types that fall within the definition used in this study.

-

Substance use disorder residential treatment. States also take many approaches to labeling, defining, and categorizing residential SUD treatment facilities. As with mental disorder facilities, crisis facilities often are so labeled (13 states), although it is clear that withdrawal management and other facilities also handle individuals presenting with high acuity. As noted above, some states have crisis facilities that are not strictly limited to mental disorder versus SUD treatment. Additionally, 35 states have SUD treatment labels that defy categorization (e.g., Specialized Treatment Facilities).[25] Facilities also were categorized as follows (see Table A2 for more detail by state):

-

States that expressly identify by label or definition the ASAM level applicable to a specific facility type, which we include if they were identified as being residential. These are Levels 3.1 (16 states), 3.2-WM (13 states), 3.3 (ten states), 3.5 (15 states), 3.7 (ten states), and 3.7-WM (12 states).

-

States may identify facilities as low, medium, or high-intensity, with or without parroting the ASAM label or level number. In some instances,[26] a state may reference ASAM with regard to these facilities, but not expressly link by level. In those instances, for purposes of the Appendix, we did not attempt to draw that connection. Rather, we relied on the state's designation as low, medium, or high. Whether identified using a precise ASAM label (e.g., Clinically Managed Low-Intensity Residential Services) or another label of low, medium, or high, 16, nine, and 16 states, respectively, fell into these categories. In some instances, states identify Level 3.3 with medium-intensity services for adults,[27] although that is inconsistent with the current ASAM criteria and reflects the older criteria.[28] In those instances, we counted the state as providing Level 3.3 services (because that is how they are identified by the state) and medium-intensity services.

-

Fourteen, 15, and five states identify detoxification/withdrawal management facilities as Clinically Managed, Medically Monitored, or Medically Managed, respectively, in accordance with ASAM criteria. Ten states identify some withdrawal management facilities as social detoxification. In some cases, social detoxification is expressly linked to ASAM Level 3.2-WM or to Clinically Managed Detoxification,[29] in which case we included it in both categories. Some states may use the term medical detoxification or medically supervised detoxification, without clear indication whether it is medically monitored or medically managed. In those instances, we included it with other unspecified withdrawal management as Detoxification/Withdrawal management.[30] A total of 23 states have facilities that we have placed into the general Detoxification/Withdrawal management category.

-

Transitional, short-term, and long-term are labels that states sometimes use to identify facilities and, when that is the case, we counted the categories accordingly, with 11 states using the label transitional, five states the label short-term, and six states the label long-term.

-

-

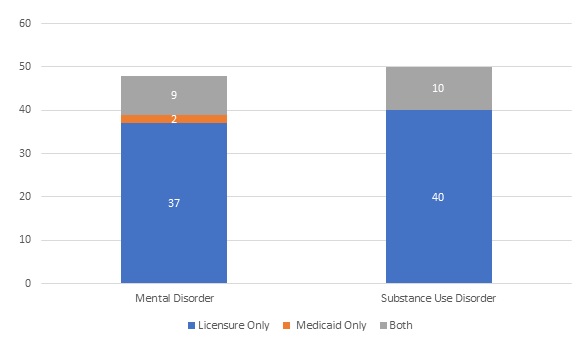

Funding criteria. In many states, regulations and/or licensing requirements vary on the basis of a facility's sources of funding. Differential regulation and/or licensure based on funding relates to whether a facility receives public funds (including block grant funds, state financing, and/or Medicaid). In Table 1, we identify the number of states that indicate requirements applicable to both Medicaid and other public funds in their regulations and licensure requirements. Separate requirements related only to Medicaid are discussed in our review of Medicaid regulations (see Section 3).

| TABLE 1. Number of States Regulated and Licensed by Funding Source | ||

|---|---|---|

| Requirements | Mental Health | Substance Use |

| Regulated based on funding source | 18 | 22 |

| Licensure based on funding source | 16 | 17 |

| NOTE: Detailed in Table A3 and Table A4. This table does not include information about requirements applicable only to Medicaid. | ||

One example of a state with multiple approaches to regulation is Ohio. Licensure by the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services is required for all residential mental health facilities.[31] Separate certification by the Department also is required if the facility provides services that are funded by: (a) the Ohio Medicaid program for community mental health or community addiction services; (b) a board of alcohol, drug addiction, and mental health services; or (c) federal or department block grant funding for certified services. In addition, other Ohio facilities may voluntarily request certification.[32]

It is important to note that regulations and licensure are not the only mechanisms that a state has to oversee publicly-funded facilities. Of the states counted in Table 1, the regulations based on funding often coexist with other regulations for a larger group of residential facilities. For the subset of facilities receiving block grant funds from the state, oversight also or alternatively may occur pursuant to contractual provisions.

Identification of unregulated facilities. After categorizing types of facilities that are regulated, we undertook to determine which facilities in the states are unregulated. This is important in order to understand areas where state oversight and regulation are not currently present. Doing so requires a thorough understanding of what is regulated. From that, one can conclude that certain facility types are unregulated. Beyond that, unless there is a clear understanding of the types of facilities that actually exist in a state, it is impossible to say that a given state contains specific types of unregulated facilities. However, states may use other levers of oversight such as legally binding contracts for facilities receiving state funds.

Our survey of the states found that residential mental disorder treatment facilities are less likely to be regulated and/or licensed than are residential SUD treatment facilities. Table A5 in the Appendix identifies states by whether they have regulation and/or licensure of every type of mental disorder or SUD residential treatment that is within the scope of this study. We estimated that 23 states have fully regulated all residential mental disorder treatment in their jurisdiction and that 39 states have fully regulated all residential SUD treatment. Of those states included in Table A5 as not fully regulating the range of residential treatment in the state, it is important to note that most, in fact, do regulate a segment of residential treatment. The following are some examples of situations in which states are classified as having unregulated or potentially unregulated facilities:

-

A state may have no licensure regulations regarding mental disorder residential facilities.[33]

-

A state may regulate or license only facilities receiving public funding, although, in some instances, private facilities may seek licensure voluntarily.[34]

-

A state may regulate a limited range of facility types, and it is impossible to determine whether there actually are any such unidentified, unregulated facilities. An example is a state where regulated residential mental disorder treatment consists of two facility types that can also provide SUD treatment, Acute Crisis Units, and Therapeutic Communities.[35] In this instance, it is possible that those two types of facilities encompass every type of residential mental disorder treatment in the state, or they may not.

-

A state may have agency staff who indicate that certain types of facilities exist but are unregulated. An example is a state in which agency staff indicated that residential mental health facilities of less than five beds are not regulated.[36]

State agency responsibility. The state agency responsibility for M/SUD oversight varies widely between states, with variability according to agency focus (either mental disorder treatment, SUD treatment, or both) as well as according to how the state assigns responsibility for regulation and licensure across different agencies. Table A6 in the appendix captures the current state of separate versus combined agency oversight. States are increasingly integrating all functions into a single agency (40 states), although many still use distinct subagencies for oversight of different types of residential treatment. Other states still administer the functions of regulation and licensure across multiple agencies according to the unique structures of the M/SUD treatment systems and public health tradition in the state. Among the latter were 12 states with agencies specifically regulating residential mental disorder treatment and 15 states doing so for residential SUD treatment. A few states had some variation on this approach to regulation. Georgia, for example has one agency regulating both with additional regulation by another agency for SUD. Kentucky, New Jersey, and Vermont have both combined and separate agencies with regulatory responsibility. We refer the reader to the state summaries (Appendix B) for further details regarding individual states.

Processes of licensure and basic oversight. The licensure process can be quite complex and entail many requirements. This may include requirements imposed through multiple processes. Thus, the licensure process may entail, for a single facility, multiple applications or processes with one or more agencies. This may apply, for instance, if a facility must be separately licensed to operate and certified to obtain public funding. In the first two rows of Table 2, we identify when this complication exists. One example is Colorado, where the Department of Human Services, Office of Behavioral Health requires designation for mental health facilities that receive public funds or that initiate an involuntary hold on a person with mental illness. This includes, among other facilities, Acute Treatment Units, which also must be licensed by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.[37]

| TABLE 2. Number of States Using Different Approaches to Licensure and Other Oversight | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirements | Mental Health | Partiallya for Mental Health |

Substance Use | Partiallya for Substance Use |

| One licensure/certification (L/C) | 38 | 0 | 41 | 1 |

| Multiple L/C | 7 | 0 | 8 | 1 |

| Duration identified | 45 | n/a | 50 | n/a |

| Inspection at L/C | 41 | 2 | 42 | 6 |

| Accreditation required | 7 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Deemed status | 14 | 7 | 23 | 8 |

| CON required | 10 | 7 | 4 | 11 |

NOTE: Detailed in Table A7 and Table A8.

|

||||

The remainder of Table 2 indicates the extent to which licensure processes offer potential for state assessment and/or oversight of facility operations and quality. To that end, we focused on four components. These include: (1) the duration of licensure, because that may affect how often facilities are examined by the state; (2) whether an inspection or survey is required at licensure; (3) whether states require accreditation by an outside entity and, if not, whether accreditation serves to offset some portion of the requirements for licensure; and (4) whether a certificate of need (CON) is required.[38] Requirements for a CON typically are found in state law and historically have been used to ensure that operation of a proposed new facility meets the needs of the community.

The duration of licensure for residential treatment varies but is specified in more than four-fifths of states (Table 2). In many states, a renewal application must be submitted annually; in a few others, the duration may be as long as 3 years.[39] Some states provide a time range during which expiration may occur. For example, Kansas regulations state that the duration is "a term to be stated upon the license, which shall not exceed two years, unless revoked earlier for cause."[40] More detail regarding the duration of licensure by state is included in Table A7 and Table A8.

Most states require an inspection or survey to be completed as part of licensure (Table 2), although some regulations appear to include agency discretion (e.g., for SUD residential treatment licensure in Texas, "If an on-site inspection is necessary, the Commission will conduct the inspection within 45 days of receiving a materially complete application packet").[41] In total, 43 and 48 states clearly require licensure inspection for mental disorder and SUD residential treatment, respectively, either fully or partially for all such facilities.

In addition to licensure, accreditation by an independent accrediting body such as TJC, the Commission on Accreditation for Rehabilitative Facilities, or the COA may be required. An actual regulatory requirement is relatively uncommon for residential treatment facilities, with 9 (mental health) and 12 (SUD) states requiring for either some or all residential facilities. Such requirements, however, may be imposed by contract, as is true in New Hampshire.[42] One example of a state where accreditation is required by regulation is Nebraska, where locked mental health facilities or facilities that use mechanical or chemical restraints or seclusion must be accredited.[43] It is more common that regulations convey "deemed status" on facilities that achieve accreditation, allowing accreditation to supplant aspects of licensure (21 [mental health] and 31 [SUD] states). For example, in Missouri, accreditation by an approved body confers deemed status, allowing an applicant for certification to submit a different application and forego a survey, other than to clarify aspects of the accreditation.[44] As another example, in Utah, the licensing agency may rely on the accreditation documentation to assist in determining if licensure is appropriate.[45] When accreditation replaces part of the licensing process, it often takes the place of inspections, although states nearly always reserve the right to conduct inspections for cause.[46]

Some states also may require a CON before a facility may be built or opened, although this is only approximately one-quarter of states for some or all facility types. This does vary by facility type, as, for example, in Florida, where a CON is required for Crisis Stabilization Units and Short-Term Residential Treatment Programs.[47] Alternatively, states may require a demonstration of need so as to obtain licensure, apart from any formal state CON requirements that may exist.[48]

Ongoing oversight. Ongoing facility oversight by state regulators, licensing bodies, or their surrogates takes different forms, providing additional opportunities for state agencies to assess facility compliance and quality. In Table 3, we identify the number of states that require: (1) regular ongoing inspections; and (2) cause-based inspections. License renewal, which typically happens at regular intervals, provides an opportunity for review of a renewal application, document review, and for renewal site inspections. Approximately four-fifths of states clearly provide for renewal inspections. States often explicitly also provide for cause-based inspections or other investigations, which may be prompted by various events, and for unannounced inspections. Among the states, approximately four-fifths have regulatory requirements mentioning such inspections. Within these requirements for routine ongoing or cause-based inspections, there are occasional nuances. One example is Texas, where the Health and Human Services Commission "may conduct a scheduled or unannounced inspection," but where it is not clearly specified in the regulation that routine inspections will regularly be required for licensure or renewal.[49]

| TABLE 3. Number of States with Requirements for Ongoing or Cause-Based Inspections | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirements | Mental Health | Partiallya for Mental Health |

Substance Use | Partiallya for Substance Use |

| Ongoing inspections | 42 | 2 | 43 | 4 |

| Caused-based inspections | 40 | 1 | 44 | 1 |

NOTE: Detailed in Table A9.

|

||||

State laws also generally provide for required plans of correction and action pursuant to those plans; actions against the license such as limitation, suspension, or revocation; and/or penalties (see Appendix B for details by state).[50] In addition, states may rely on contractual provisions for entities receiving public funding through block grants, Medicaid, or other avenues to activate oversight at times other than upon renewal. Thus, even if provisions were not located in the licensing regulations regarding ongoing or cause-based inspections, it is very possible that such requirements exist in other formats.

Domains Regarding Facility Operations

Domains regarding facility operations include standards regarding access to treatment, staffing, placement, treatment and discharge planning and aftercare, treatment services provided (including medication-assisted treatment [MAT]), service recipient rights, quality assurance or improvement, governance, and requirements related to special populations.

Access to treatment. Access to the full continuum of behavioral health treatment is a persistent problem and multiple barriers to accessing care may exist. Regarding access to residential treatment, this study examines whether states impose requirements regarding wait time to access treatment. This was selected as a discrete measure of whether access is explicitly addressed in the regulations. About a third of the states have wait times or requirements regarding wait time facility policies present in the regulations (15 [mental health] and 17 [SUD], partially or fully) (see Table 4). Where such requirements exist in the regulations, they may appear as a general mandate[51] or as applicable to certain facility types only (e.g., South Carolina crisis stabilization units or Idaho withdrawal management).[52, 53] A different approach is taken by Missouri; its regulations include what are called "Essential Principles" that are intended to guide the facility. Among the Essential Principles is "Easy and Timely Access to Services," in which the Department of Mental Health suggests (but does not require) that some potential performance indicators for mental health services generally might include: (1) same-day access to services; or (2) reduced wait time to set a first or subsequent appointment(s).[54] There also are instances in which wait time requirements are applied through nonregulatory means. For instance, staff from both Arizona and Tennessee indicated that they have online portals to manage wait times. Although these are not included as regulatory requirements, they do exist and are addressed in the respective state summaries (Appendix B). Several states have wait time requirements specific to priority populations, which is discussed further under Special Populations. We also discuss, under Treatment Services, regulatory requirements that access not be denied because a person is receiving or has received MAT or, in the case of mental health facilities, has an SUD.

| TABLE 4. Number of States with Regulatory Provisions Regarding Wait Times | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirements | Mental Health | Partiallya for Mental Health |

Substance Use | Partiallya for Substance Use |

| Wait times | 9 | 6 | 8 | 9 |

NOTE: Detailed in Table A10.

|

||||

Staffing standards. Qualified staff at all levels are important to the provision of quality care in residential treatment. Many states include explicit staffing requirements in regulations,[55, 56] whereas other states may rely more heavily on incorporation by reference, such as of ASAM staffing standards for SUD residential treatment, which Iowa staff indicate are applicable,[57] or, perhaps, on requirements placed in policy documents or contracts. For this study, staffing was examined from two perspectives: (1) regulatory requirements related to required staffing, credential or experience requirements, and required levels for staffing; and (2) regulatory requirements regarding staff training.

The focus for the first was on quantifiable standards, such as whether there are any requirements related to facility administrators, medical directors, other medical staff, clinical staff, or direct care staff, and the extent to which staffing ratios or other criteria for staffing levels exist (Table 5). States may approach this as simply, for instance, requiring that there be an administrator, or, instead, may specify acceptable age, educational credentials, and/or experience. Mental health residential facility regulations are somewhat less likely than SUD regulations to have administrator requirements. States are much less likely to require that facilities have a medical director and are even less likely to require that to be a physician.[58] Within the realm of residential SUD treatment, requirements for a medical director or even medical staff were most common in residential detoxification or withdrawal management facilities as opposed to other types of residential treatment.[59] Requirements related to clinical staff refer to licensed mental disorder or SUD treatment providers such as psychologists, social workers, or drug and alcohol dependence counselors. Among the states requiring that substance abuse counseling generally be provided by licensed drug and alcohol dependence counselors are a few that expressly except from that requirement otherwise licensed professionals such as physicians or psychologists.[60] Direct care staff, as that term is used in this Compendium, means nonlicensed staff, or peer staff who may be certified, who are charged with day-to-day contact with residents. In all instances, SUD regulations are more likely to specify such staffing requirements.

| TABLE 5. Number of States by Staffing Standards for Licensure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirements | Mental Health | Partiallya for Mental Health |

Substance Use | Partiallya for Substance Use |

| Standards | ||||

| Administrator | 32 | 5 | 34 | 6 |

| Medical Director | 7 | 4 | 7 | 12 |

| Medical staff | 23 | 9 | 20 | 24 |

| Clinical staff | 3 | 2 | 37 | 10 |

| Direct care staff | 30 | 4 | 31 | 6 |

| Staffing levels | ||||

| Ratios | 18 | 9 | 17 | 17 |

| Adequate | 26 | 4 | 31 | 10 |

NOTE: Detailed in Table A10, Table A11, Table A12.

|

||||

We also examined the extent to which states incorporate staffing ratios or requirements for policies regarding ratios into regulations and/or require that there be "sufficient" or "adequate" staffing. In some instances, a state may use both approaches, often depending on facility type.[61, 62] When ratios are prescribed, it typically is for certain types of personnel and not others (e.g., nursing staff, clinical staff, direct care staff). Again, this is somewhat more likely to be seen in SUD regulations than in those governing mental health residential facilities. It also is likely that states without explicit ratios in regulations do include them in other policy documents or contracts.

For the second aspect of staffing, we looked at orientation and ongoing training requirements, as well as two selected potential foci of training, specifically staff training regarding trauma-informed care and regarding suicide assessment and/or prevention (or crisis intervention). Table 6 provides basic information on training standards that are incorporated into state regulations. Training requirements vary greatly. Some are specific as to orientation versus ongoing training, whereas others are not explicit about the timing for training. Some state regulations go into great detail about mandatory or optional training required of staff generally, in contrast to others that focus on training for specific staff types. Some, such as regulations governing personnel in residential mental health facilities in Iowa, vary the training requirements by level of care, for example, placing greater emphasis on training for staff at Intermediate Care Facilities for Persons with Mental Illness[63] than at Residential Care Facilities with a Three to Five-Bed Specialized License.[64]

States have many different areas on which they may elect to focus staff training. Training subjects range from first aid to dual diagnosis to restraint and seclusion (R/S), with many other topics emphasized by different states. More than four-fifths of states use regulations as a way to impose training requirements. The training requirements are highlighted in Table 6; training regarding trauma-informed care and regarding suicide assessment and/or prevention, are just two out of many possible subjects of regulation-mandated training. They were selected, however, because trauma-informed care is generally regarded as a best practice in both mental disorder and SUD treatment and because training related to suicide was selected as an indicator of focus on safety. More states require use of trauma-informed care, sometimes in conjunction with other requirements that staff be "qualified" to perform their job responsibilities, than do states that explicitly require staff training in trauma-informed treatment. One example of the former is Mississippi, which requires that all services be designed to provide trauma-informed care but does not include a specific regulatory requirement related to training in such care.[65] Similarly, although crisis services may be a fundamental part of the treatment spectrum in many states or suicide assessment explicitly must be conducted, not all state regulations are explicit in requiring more general suicide assessment and prevention training for staff. An example is Missouri, which requires suicide screening as part of admission assessment, "competent staff" to identify risks and behaviors that can lead to a crisis and the use of "effective strategies to prevent or intervene," the development of crisis prevention plans where at-risk behavior including suicide is identified, and "ready access to crisis assistance and intervention ... provided by qualified staff," but does not include an explicit requirement for suicide prevention and assessment training.[66] We include in Table 6 only those states that are explicit about requiring trauma or suicide-related (or crisis-related) training in regulations.

| TABLE 6. Number of States by Training Requirements for Licensure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirements | Mental Health | Partiallya for Mental Health |

Substance Use | Partiallya for Substance Use |

| Orientation and/or ongoing training | 31 | 10 | 36 | 11 |

| Trauma-informed care training | 4 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| Suicide assessment/prevention training | 6 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

NOTE: Detailed in Table A13.

|

||||

Staffing in residential care is one of the few domains that was explicitly addressed in earlier research. Our scan found much lower rates of required training than was found in data from two short reports by the SAMHSA. SAMHSA examined this subject for mental disorder and SUD specialty treatment, using 2010 N-MHSS and 2013 N-SSATS data.[67] Those analyses examined three markers of quality assurance practices related to facility workforce. Practices varied considerably by state and by type of organization (e.g., private for-profit, private nonprofit, state government entities, Veterans Health Administration). Table 7, however, shows the results for the three measures in residential treatment settings for mental health and SUD respectively.

These measures reflect the data available from the surveys, which are voluntarily reported, but generally indicate that large numbers of the residential facilities surveyed followed these practices. These are not comparable to the data collected as part of this study, which relate to requirements found in state statutes and regulations and include neither facility-required training nor requirements imposed by nonregulatory sources. Nonetheless, even state statutes and regulations frequently include training requirements. These studies, however, highlight the widespread use of two practices that should be a basic part of treatment delivery, in particular, continuing education and regular case review with a supervisor, and a third less commonly used practice of case review by a quality review committee.

Placement standards. Placement in the appropriate setting and level of care is important to ensure that patients receive the care they need. For example, research shows that receiving SUD treatment in the appropriate type and intensity of care can positively affect treatment participation and retention, reduce use of more intensive services, and result in better outcomes than is true for those placed in a lower or, in some instances, a higher level of care than is recommended[68] by the ASAM Patient Placement Criteria.

To determine whether state placement oversight exists, we examined whether there were specific criteria for placement and/or assessment, including whether regulations delegated this function by way of facility policy and procedure requirements. Within the realm of SUD treatment, we looked at regulatory requirements related to use of the ASAM Patient Placement Criteria. Also included in the state summaries (Appendix B) are requirements regarding continued placement and discharge criteria.

Placement standards within state licensing regulations generally fall into four categories, more than one of which may be present in any given state:

-

Specific statements in the law about the population intended to be served by a given facility type.[69]

-